Mental Health Awareness Week 2026 – What, when & best resources

Mental Health Awareness Week is almost here and we’ve got some great resources that will help your students to thrive…

- by Teachwire

- Classroom expertise and free resources for teachers

As Mental Health Awareness Week approaches, explore how you can support your students’ wellbeing and promote adaptability…

What is Mental Health Awareness Week?

Mental Health Awareness Week started in 2001 and is run by the Mental Health Foundation – a leading UK charity. The week aims to tackle stigma and help people understand and prioritise their and others’ mental health.

The theme for 2026 is ‘Action’.

When is Mental Health Awareness Week?

Mental Health Awareness Week 2026 takes place between 11th-17th May.

Other mental health events

World Mental Health Day takes place on 10th October every year. The next Children’s Mental Health Week is in February 2026.

What to do for Mental Health Awareness Week

KS1/KS2 lesson plan

This free lesson plan for KS1 and KS2 explores ways pupils can become more connected to both their peers and their community in fulfilling and meaningful ways. It also touches on connecting with yourself to overcome life’s challenges.

The lesson covers using nature to improve connections, what a growth mindset is and how to use positive self-talk. Pupils will also learn about the importance of kindness and how to put it into action.

Host a Wear It Green Day

Organise a Wear it Green Day in your school to raise vital funds and awareness for mental health. Register online to download your free schools pack.

Key Stage 1 and 2 activity packs

Explore emotions with KS1 and KS2 children with this free bumper activities pack from Plazoom. Help pupils to identify different emotions using the image and word cards and discuss examples of when children, or their friends or family, have experienced these emotions.

You’ll find question cards and question stems included to prompt conversations about what positive steps children can take if they experience a particular emotion.

Activities for both KS1 and KS2 are included, with teacher advice for how to use the resources in the classroom.

Recharging your mental battery

These free mental health worksheets help children and young people identify what drains and restores their emotional and mental energy.

Designed for different age groups – primary (Year 5+) and secondary (Year 8+) – these resources encourage self-reflection on daily challenges and uplifting activities, providing practical strategies to support emotional wellbeing.

Mental Health Awareness Week virtual assemblies

The 52 Lives charity is running a virtual assembly at 9.15am and 1.30pm on Monday 12th May 2025. It will cover what Mental Health Awareness Week is, this year’s theme, simple ways you can incorporate movement into your day and the role kindness plays in improving mental health.

The charity also has lots of free lesson plans and activities that you can use to teach children about the importance of kindness.

Mental health activity pack

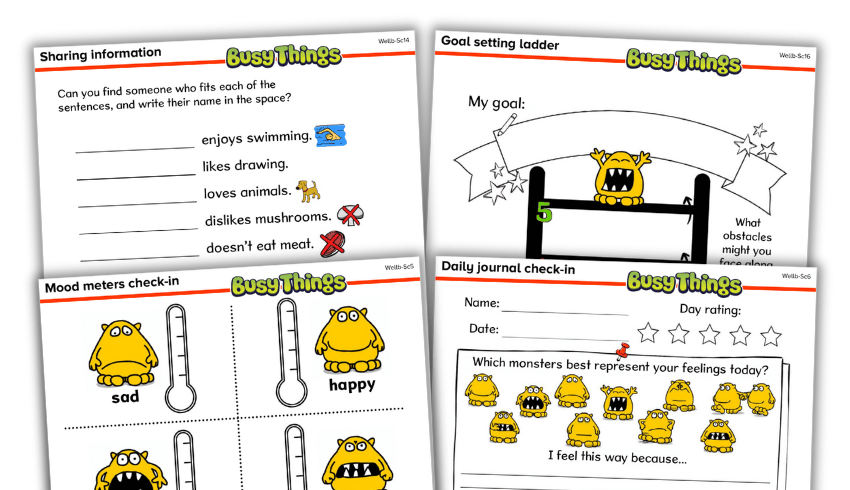

Packed with engaging children’s mental health activities, this free resource promotes resilience and empathy through tools like brain breaks, daily journals and creative mindfulness exercises.

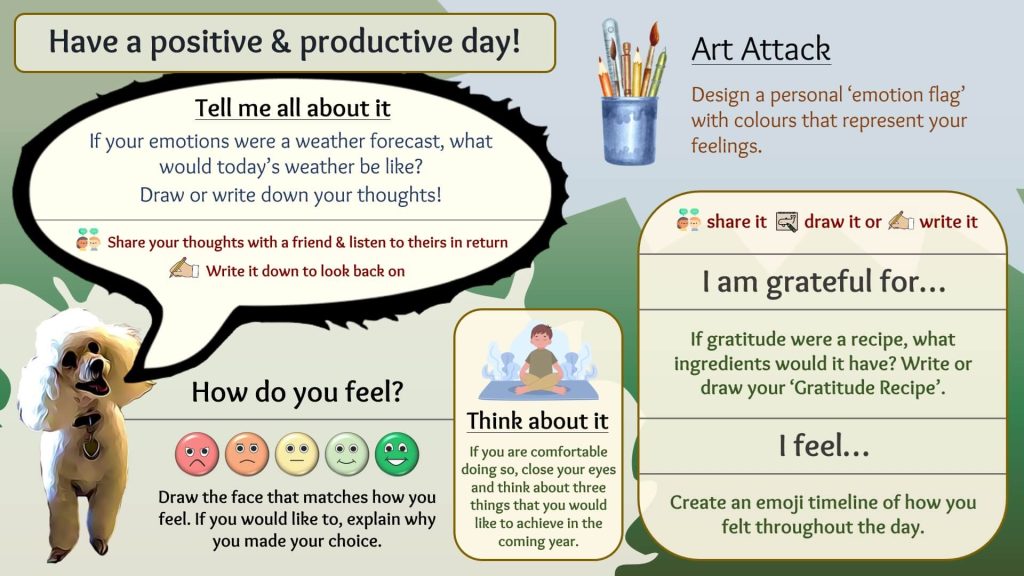

Morning Challenge wellbeing slides

Download a week’s worth of free wellbeing slides from Morning Challenge and display them on your board when children enter the classroom. The activities are designed to help with mindfulness, emotional intelligence and more.

Premier League Primary Stars resources

Premier League Primary Stars is marking Mental Health Awareness Week with a free teacher webinar on Thursday 15th May at 4pm. It will offer practical strategies to boost pupils’ self-esteem, wellbeing and resilience – with insights on the power of physical activity.

There are also free, curriculum-linked KS1 and KS2 wellbeing resources – perfect for use during the week and beyond. These cover building self-esteem, healthy eating, emotional regulation and more.

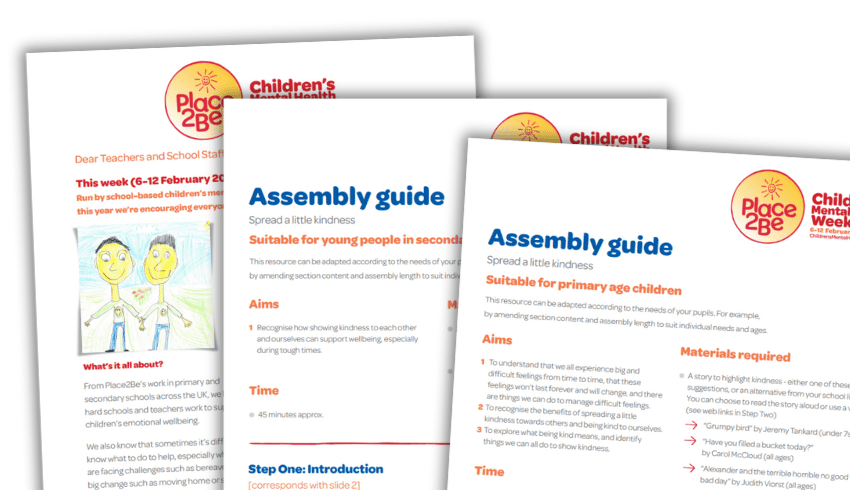

Kindness assembly

These two kindness assembly resources – one for primary and one for secondary – can help you spread a little kindness in your primary or secondary school. You’ll get slides, teacher notes and recommendations for videos and stories to use in your assembly.

Free resource pack from imoves

Online digital platform imoves is offering a free resource pack containing no-prep Active Blast videos, fun classroom-based activities focused on emotional wellbeing and self care and teacher guides/videos.

Wellbeing toolkit for primary schools

Three education charities have joined forces to launch a free online wellbeing toolkit based on the NHS framework for primary schools. It’s designed to support children’s mental wellbeing and boost resilience.

There are lots of resources, lesson plans and activities adapted for different ages and the toolkit is split into five sections: Connect with others; Be active; Take notice (mindfulness); Learn and create; Give to others.

Teaching about feelings KS1 unit

This free six-week series of lessons will help you to teach about feelings in KS1. The lessons focus on helping children to be able to express themselves and understand that all emotions are equally valid. Accompanying PowerPoints and worksheets are included in the download.

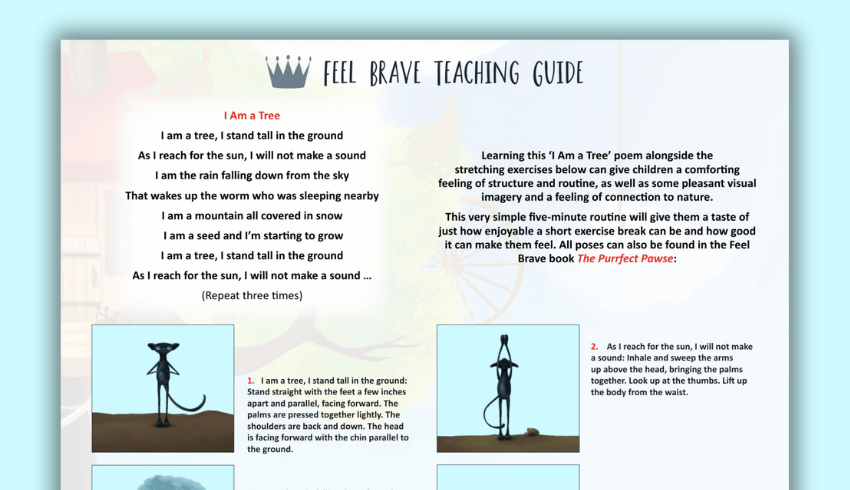

Five-minute yoga routine

Looking to bring yoga into your primary school? This thoughtfully-designed five-minute yoga routine blends movement, breathwork, and poetry to lead children through a calming series of nature-inspired stretches.

Senior mental health lead training

Senior mental health lead training: a whole school approach is a DfE quality-assured online training course that teaches you how to implement a whole-school approach to mental health.

Self harm support resources

Helping students who self-harm isn’t easy, but with the right tools and approaches, teachers can have a real impact. These self-harm support resources from SORTS (a group of academic psychologists based at the University of Cambridge) have been developed in collaboration with mental health experts, educators and young people.

How to help children cope with change

Support all pupils through tricky periods with this six-step plan…

Helping young people cope with change has never felt more important or demanded such a lot from educators. Change is an inevitable part of life, and it can provide opportunities to develop resilience, optimism and adaptability.

For those with SEND, existing anxiety, limited home support, possibly those with transient backgrounds change at the best of times can be overwhelming. Feelings of stress, anxiety and overwhelm are common.

Supporting all students

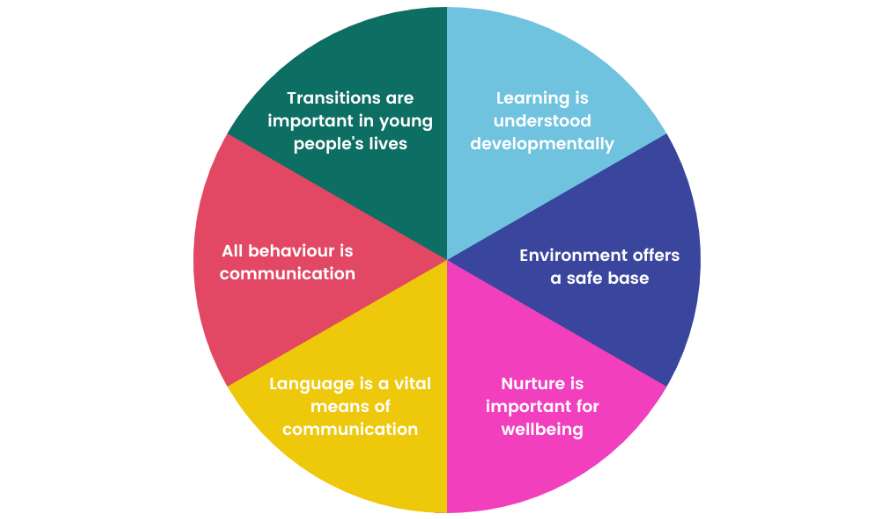

The six principles of nurture are needed throughout the year to support all pupils, though especially those who are more vulnerable. The principles are:

- We understand learning developmentally. As our understanding of neuroscience increases, so does our understanding that young people develop, socially, emotionally, physically and intellectually at different rates. So we need to work with them as they are, which increases their sense of safety and security.

- Environment offers a safe base. Classrooms should be a safe place with reliable and consistent adults, structure and routine.

- Nurture is important to wellbeing. Listening and responding appropriately, as well as showing young people they are valued, is essential.

- Language is a vital means of communication. It is vitally important for young people to have a voice, have space to express themselves in their actions and words, and be listened to.

- All behaviour is communication. We need to understand the feelings and needs that children are expressing. Transition can be a time of challenging behaviour.

- Transitions are important in young people’s lives. There are multiple transitions in all our lives and these principles can support young people day in, day out.

School transition

All children need us to pay additional attention to their wellbeing and mental health. Especially during the end of one school year and the start of another.

Pupils may be feeling happy and recognise the success and achievements of the year that has passed, but they may also be feeling overwhelmed, anxious and stressed. Feelings and emotions (and therefore behaviour) can be wildly varying from excited, to curious, to nervous.

Giving all pupils a character-strength-based vocabulary can help them recognise the strong points that they have already developed, and how these can support them in their next phase of life.

Focus on strengths

Here are some examples of how an understanding of character strengths can support transition and mental health:

Adaptability

Use a positive affirmation, such as ‘I am flexible. I can adapt my feelings, thoughts and actions to suit the situation’. By developing our adaptability, we learn to adjust to different situations. This helps us grow our confidence to deal with uncertainty and unfamiliarity.

Therefore, explicitly teaching students about adaptability – perhaps finding examples in role models and stories – can provide a useful tool for dealing with change.

Creativity

‘I can think differently. I can see the world in new ways, making unusual connections’. There are myriad studies on how being creative is good for our wellbeing and mental health.

A BBC Arts study of 50,000 people found that even minimal creative activity boosts positive mental health and helps people manage their emotions, build confidence and explore solutions to problems. This is regardless of the level of skills involved.

We also know that developing our imagination through art, music or other creative subjects releases ‘feel-good’ chemicals such as dopamine and endorphins.

In addition, creative thinking allows us to find new solutions to tricky problems. Difficult situations are always going to arise; how great to offer a means of finding solutions to them!

Open-mindedness

‘I enjoy difference and am open to different people and ideas. I consider different options before making a decision’. This is such a key area when thinking about transition and the new year ahead.

Learning that taking time not to judge and label others actually boosts our happiness and results in better quality friendships in an invaluable life lesson.

Resilience

‘I can keep going and bounce back from setbacks’. Being resilient and bouncing back from difficulties and not being stressed by them, changes how we feel.

Resilience can also reduce the impact of past negative experiences. Transitions are important and unavoidable in young people’s lives. Giving them a toolkit of strengths helps them navigate change successfully.

Selena Whitehead has 25 years’ experience in education, both in the UK and overseas. She is a qualified citizenship teacher and worked as a supply teacher across primary and secondary schools in York.