In Search Of The Male SENCo

Male SENCos tend to approach the job differently to their female counterparts, says Dr Mark Pulsford – and if we care about gender equality, we might want to start looking at why…

Exactly how many men work as SENCos in schools in the UK isn’t known, since it’s not a recorded statistic – but talk to almost anyone within the education sector and you’ll be hard-pressed to find someone who can point you in the direction of a male SENCo. I know, because I’ve asked.

I did eventually manage to find four, though, who agreed to take part in an in-depth research study funded by the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) on their experiences of being male and working as SENCos in English primary schools.

Motherly, selfless care

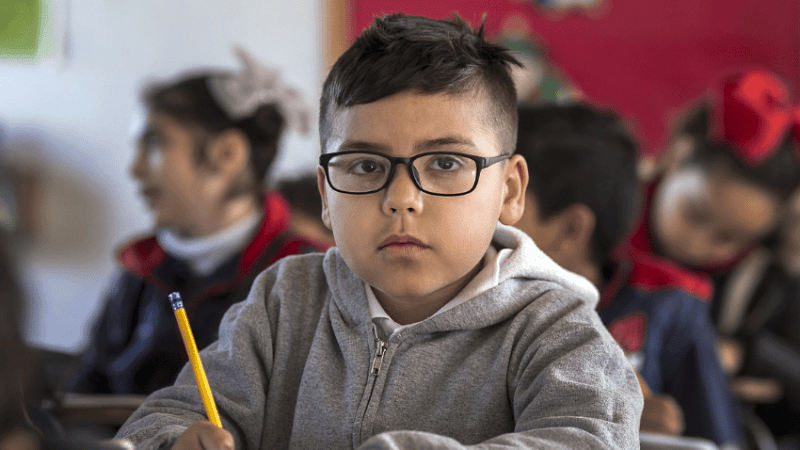

The role of SENCo has an historical legacy that links it with forms of motherly, selfless care. Evidence from National Award for SEN Coordination providers suggests that most people signing up for their courses are women in their 30s and 40s.

Associated with the role is a host of assumptions about the skills and attributes needed to work with some of the most vulnerable and most in need pupils in our schools. Yet it was common for the men in my research to report being barred from accessing that particular type of identity as a SENCo, despite feeling a great affection for the pupils and professing a love for the sort of work they are involved in.

One of the participants, Graham, when talking about how parents reacted to him as the new SENCo put it like this: “The old SENCo, Mrs Jenkins was ‘lovely’. And then along I come, this young lad, and hang on… ‘You didn’t go in and give my child a hug in the morning?’, you know? ‘Who are you to tell me anything – how do you know my child?’

But as Simon, another man in my research pointed out, any physical contact with children can be seen as suspicious: “A woman in my position would probably give a cuddle, probably have a child sat on their lap and things like that, whereas I wouldn’t – I don’t feel I could do that. Even if that’s what the child needed, it still probably wouldn’t be any more than a hand on the shoulder.”

A prominent theme in the accounts the men gave was that they found life as a SENCo to be more straightforward if they fitted with some stereotypical behaviours associated with men, such as being seen as efficient, procedurally focused and an authority on the subject of SEN. These men would often adopt a ‘SEN expert’ position, from which a ‘managerial’ type of SENCo emerged in their stories.

This identity would be characterised by the way they worked with the instruments of SEN, those tick-boxes of learning difficulty diagnoses and files containing information and intervention plans becoming important props. The men’s office spaces, where we spent hours during our interviews, were shrines to procedure and process, to paperwork and paperclips.

Another beacon of these men’s SENCo identity was the suit, shirt and tie. This business-like attire was a symbol of their status and a marker of their authority when it came to special needs in their settings. In sum, a certain vision of SEN provision could be glimpsed here – one which in its starkest form looked far from pupil-centred.

Lasting impressions

The forging of these ‘male SENCo identities’ has potential consequences that all of us – men, women, headteachers, NQTs and SENCos alike – need to be mindful of.

It reinforces the notion for children that it is not a man’s role to care for them in ways such as hugging them and getting to know them well. It cements the gap between men and children, makes it seem normal for men to maintain their distance and can affirm and preserve the gender divide when it comes to ‘caring roles’. There may appear to be a naturalness or common sense to this divide, yet it’s a key factor in the continuing inequalities in pay and status between men and women.

If men face pressures not to demonstrate their care, and are therefore not seen to be caring, surely this undermines the impact of gender equality efforts aimed at supporting women into leadership positions? School is one of the first places where children see adults at work; any gendered role distinctions they see are likely to leave lasting impressions.

Daily enactments of the SENCo role

The experiences of the male primary SENCos in my research suggested that caring in ‘maternal’ ways is often expected of SENCos. With this approach effectively out of bounds for them, however, they had to adopt other modes of being instead. This complex negotiation of gender identity and the role of the SENCo is worth considering in some depth, so that educators can find ways of smoothing out such deeply gendered distinctions regarding the SENCo’s purpose.

Yet whilst it seems important to have more men working as SENCos in our schools, there are some ways of working towards this goal that I would caution against. One might be the perceived need to improve the status of the SENCo role, or to mount an inspirational recruitment campaign using a male SENCo ‘role model’.

I’d suggest that these solutions would merely feed the existing narrative that men require (and deserve) kudos and prominence in order for a job to appeal to them, and might further erase the caring dimensions of the role in favour of promoting ‘professional’ competencies, while framing the work that women already do in these roles as inferior.

Instead, I think there is value in examining how those parts of the SENCo role that became prominent for the men in my research lend themselves to being gendered – the ways SEN data is collected and managed; the holding on to or dissemination of ‘expert’ knowledge; the clothing and office accessories that signify openness or enforce a sense of distance; and the nature of daily interactions with pupils as a result. These everyday enactments of what it means to be a SENCo will work to encourage or put off other teachers in school that otherwise might aspire to take the role in future.

Perhaps instead of asking why there are so few male SENCos, we should ask how the women and men currently working as SENCos can start actively countering the daily gendering of the role?

“I was thrown onto the ‘glass escalator’”

Some further thoughts from the participants involved in Dr Pulsford’s study:

Charlie, on facilitating discussion between colleagues regarding good practice and inclusion: “That is care, isn’t it? Being able to talk to each other, and being able to do something you’d want the children to be able to do, rather than top-down leadership.”

James, on forging networks within and outside of the school: “Word’s getting out that the partners we have are professional, that they help and that it’s successful, so the school is becoming known as a caring environment”

Simon, on becoming a SENCo to advance his career: “I was thrown onto the ‘glass escalator’, like many male primary teachers before me – but I developed a love for the role and intend to stick with it, because I saw the difference I could make.”

About the author

Dr Mark Pulsford is a former primary school teacher and now programme leader for the MA in Education Practice at De Montfort University