How to make the most of every minute in the classroom

As COVID-19 upends the usual Y11 preparations and milestones, Adam Riches looks at how teachers can make the best of use of every minute in the classroom…

- by Adam Riches

- Teacher, writer and educational consultant

Time pressures are now an issue like never before. For those of us in classrooms, the learning we’ve lost learning has added considerably more weight to the already heavy burden of curriculum pressure most of us are under.

It’s a situation that contrives to add ever more stress and anxiety to the process of preparing and delivering learning – but all need not be lost.

Effective and efficient practice can maximise lesson time. Getting the ‘what’ and ‘how’ right is vital to succeeding, and by dropping some more time-hungry pedagogical approaches, it’s possible to rapidly streamline your teaching.

Let’s look at some surefire ways of ensuring you get the most out of every precious minute you spend with your classes…

Start where you left off

Good routine is paramount here. If students know your expectations from the outset, the tone of the lesson will be set. Keep your lesson starts short, sweet and relevant.

Briefly revisiting learning from the previous session, previous week and previous month will help students to build schema.

As I rule, I like to aim for five minutes of thinking and doing and two minutes of feeding back and discussing, so that new learning commences around seven minutes into the lesson.

The number of minutes is somewhat arbitrary, but the general idea is that lesson starts should be short and focused.

As well as settling students into the learning environment, a structured start to the lesson will do much to set the tone for what follows.

Ensure the lesson’s main objective is displayed on the board when students enter, and set the expectation that they need to be getting on with the tasks set from the moment they sit down. The beginning and end of lessons are when most time is lost.

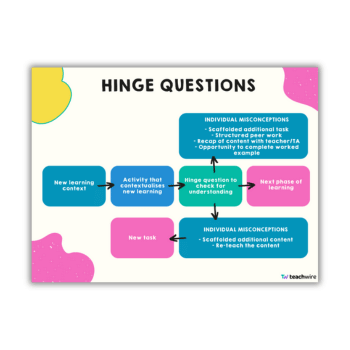

Summarise phases with hinge questions

Once new learning is happening, you need to make sure that students get what’s going on. Moving forwards too fast can create gaps which in turn lead to greater difficulty and confusion further down the road.

Summarising each phase of the lesson with some kind of check will allow you to quickly ascertain, understand and stem any arising misconceptions. It’s less about students getting things exactly right and more about you mopping up where needed.

My preference is to use quick, two-minute tasks such as composing a well-formulated sentence to explain X or Y, either in writing or expressed verbally.

When planning, make sure you know what these vital hinge questions should be, because they will be your temperature check. Think, ‘What’s the key take away?’

Model, model, model

I can’t emphasise enough how important it is to model if you want to teach effectively and efficiently.

The idea that ‘students need to discover for themselves’ will only produce a time drain, given the quality of responses you’re likely to receive. That approach arguably has its place, but direct instruction rules here.

You’re the expert, and giving your students a blueprint to follow will help with both their cognitive load and your time limitations.

Live modelling is especially effective. Providing a commentary adds to the metacognitive potential, and will allow students to feel the processes they need to follow to succeed.

Yes, you’ll need both good subject knowledge and confidence in what the exam content will consist of, but if you’re looking for ways to improve your practice, this is a good place to start.

Premise models are okay too, but they can sometimes feel manufactured and students won’t get the same level of instruction from them. They can also take time to create, without producing tangible time savings in lessons, which is something to think about.

Embed useful scaffolds

Similar to modelling, scaffolds allow for extra task-specific support. The difference is that scaffolds allow you to build towards independent practice.

Well-paced scaffolds can help save time by supporting students through more challenging tasks. When you’re trying to keep the difficulty desirable in the face of time restrictions, scaffolding will let you do both at once.

The scaffolded resource can support the learning, leaving you to focus on those for whom the resource isn’t helpful.

Scaffolds needn’t be complicated. Try breaking your scaffolds into two categories: those that support on a detailed level – say, a word bank or sentence openers – and those that can be used to support on an overview level, such as a paragraph structure framework.

Whether you decide to prepare these ahead of time and hand them out or display them in front of the class, you’ll eventually need to remove them as time progresses.

My advice is to keep your scaffold format and wording consistent. This allows students to signpost and learn the scaffolds more easily, make better use of them during independent work and ultimately develop a better understanding of the relevant process. Calling a scaffold ‘key words’ one day and ‘vocabulary bank’ the next will soon become confusing.

Check for understanding

Take every opportunity to ensure students’ learning stays on track. You’ll ultimately want to ensure that their learning journey reaches the destination on time, as planned. You don’t want to take any massive detours – small adjustments throughout are a much better way to go.

Depending on the situation in your local area, given the present climate, this may be much harder than it normally would be. That said, questioning, talk and discussion are great ways of checking understanding from afar.

Use what time you have to build a picture of any misconceptions and decide whether to address these during the lesson itself, or afterwards using some form of feedback.

I like to address anything that’s important for the present lesson immediately, and note down misconceptions that might cause wider issues before addressing these in dedicated feedback time. This helps keep the learning focused.

Plan for talk

Planning in talk time will give your lesson phases value and direction. More often than not, talk tasks are only partially planned. You’ll want to consider the specific instructions, outcomes and value, and make sure that students are spending this time in the lesson wisely.

Allowing a 15-minute pair discussion would be a travesty. Peak talk time is two minutes, and students need to be doing something focused with their talking.

Planning your talk time around specific windows will enable you to build a culture around silence – which is much easier to achieve when you’re clearly in control of the learning talk.

Allow time for independent application

You delivering and students retaining knowledge is one thing, but we all know that the proof is in the pudding. Don’t assume that what’s been learnt can always be applied.

That’s why you should give students time to independently apply what you’ve taught them.

Not only does this complete the circle of learning, it also heightens the challenge and ensures that what’s been learnt can be used in context.

Knowing something doesn’t necessarily mean you can translate it into the format required by an exam.

Take this opportunity to perform your final check for understanding. You may choose to take this work in or, if you’re like me, trawl during the task for signs of misconceptions.

Time is a luxury we don’t have when we’re in the classroom, now more than ever. An effective teacher will ensure that learning happens as efficiently as possible.

It’s not about spending hours preparing and making resources; it’s about working as smartly as possible, and keeping your pedagogy and planning sharp.

Adam Riches has taught for five years. He is currently head of KS5 English language/whole school literacy coordinator at Northgate High School, Ipswich.