Differentiation in teaching – Simple ways to meet everyone’s needs

We explore what differentiation is, the various types, practical approaches and how to use edtech to assist…

- by Teachwire

- Classroom expertise and free resources for teachers

Differentiation in teaching is something that seems to cause a lot of angst. But really it shouldn’t – it’s what effective teachers do naturally.

If a pupil doesn’t understand, you’ll explain it in another way. If a pupil is finding something too easy, you’ll move them on to something more demanding.

You are constantly receiving feedback from your pupils just by watching and checking; differentiation is simply what you do as a result.

What is differentiation in teaching?

Differentiation in teaching is about understanding what your children already know and can do, and responding to that knowledge in a way that moves their learning forwards.

You might see it defined in an inspection report as ‘setting work at the right level of difficulty for individual pupils.’

The word ‘differentiation’ can cause concern, because it conjures up the nightmare of preparing three different worksheets for every lesson – one for the strugglers, one for the middle and one for those who need stretching.

But in reality, differentiation in teaching can come in lots of different forms.

“It conjures up the nightmare of preparing three different worksheets for every lesson”

There is no point in teaching someone something they already know, and some learners know a lot more than others. If we don’t do anything to adapt to this, we run the risk of wasting learning time.

For everyone to make maximum progress in class, there needs to be enough support for those who struggle and enough challenge for those who might find the lesson easy.

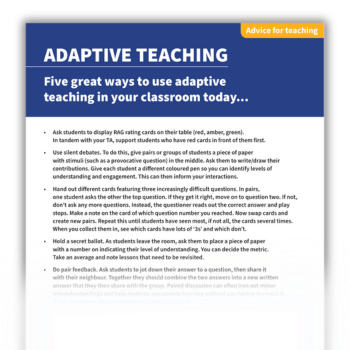

A useful way to think about differentiation is as responsive teaching. Often, it is about adapting ‘in the moment’ as you realise how much (or how little) your children understand about what you are teaching them.

“A useful way to think about differentiation is as responsive teaching”

Types of differentiation in teaching

Differentiation by instruction

This is the subtlest but the most common differentiation we undertake in our classrooms. It happens so continuously, that it is actually hard to note when we are not doing it. It is implicit in every question we ask and the feedback that we share.

By concentrating our efforts upon making the implicit core business of questioning and feedback more explicit, we can make the detail of differentiation concrete, so that we can understand how to do it even better.

Differentiation by outcome

This is where all children are given the same task and objective and complete it at their own level. This is typically quick and easy to do. However, it can lead to inadvertently lowering the effort of some young people and limiting their potential.

To make differentiating by outcome successful, you don’t need to provide multiple tasks. Instead, you should simply choose one great outcome. Crucially, that outcome should prove challenging, flexible, open ended and meaningful.

Differentiation by classroom support

All children have the same task but some receive more support than others. If you are lucky enough to have teaching assistants, they can provide expert small-group instruction or you can flip that model and work with that group yourself while your TA takes the lead with your class.

Differentiation by support tools

Some tools can be low-effort but have high impact – for example, a literacy mat, a usable checklist or some well-placed exemplar models.

By encouraging students to self-select such carefully targeted tools, we not only encourage differentiation, but also empower our students to learn far beyond the reaches of the classroom..

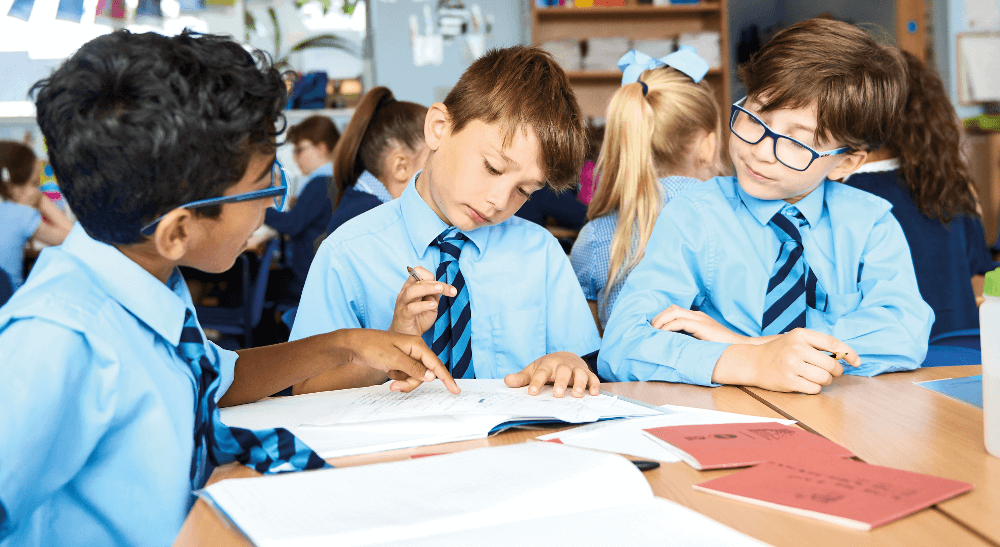

Differentiation by group work

Be proactive with your within-class groupings to better match the task to the speed and need of students.

There is a range of grouping styles you can try – by similar ability, gender, personality or friendship. Harness the competitive urge in your students, while taking care to keep such groupings flexible.

On many occasions, mixed seating works well as it encourages peer learning (and teaching). At other times, it is useful to bring children with a similar need together for some brief, focused skill-teaching.

Or you may assemble a group of current high achievers to go deeper, and then explain their new learning to the class.

Differentiation by task

This involves giving children different tasks based on their ability. This way you can see the work achieved and personalise it for each child. This can take a long time to organise, however.

Differentiation by questioning

When done well, this has a tremendously powerful impact on learning. By adjusting the level of challenge in questions and using probing ‘follow up’ questions aimed at individual pupils, we can stretch the most able.

We can also encourage the less able to develop clarity in their thinking and the ability to articulate their answers.

- How to teach mixed ability MFL lessons

- How to make differentiation in maths work

- What adaptive teaching is and why it’s important

- How to teach EAL students

- Using Blank Levels of Questioning in your classroom

How to differentiate in teaching

Sue Cowley, author of The Ultimate Guide to Differentiation, sets out seven ways to do differentiation in teaching…

1) Work out what they already know

When starting a new topic, rather than assuming your children know nothing about it, start by working out what they already know and what they want to find out.

You could do a quick assessment, or you might ask them to write down one thing they already know on one side of a sticky note and one question that they’d like answered on the other.

You can put these notes up on a working wall and use the questions as a stretch activity during your studies.

2) Ask children to be teachers

Sometimes the children will have as much or possibly more knowledge than you about a topic – a child who is fascinated by dinosaurs, or a child who has visited or even lived in a country you are studying.

Get the child to ‘be teacher’ and incorporate their prior knowledge into your lesson by teaching their peers.

My child’s class began to study China as their topic, shortly after we had returned from three weeks in the country. The teacher sensibly asked my child to bring in some souvenirs and to tell the class about our experiences there, to bring the class topic to life.

3) Think about targets and time limits

A straightforward way to increase differentiation in your lessons is to think about how you use targets and time limits. More is not necessarily better.

For instance, setting a target to write an explanation in 10 or 20 words is more challenging than writing a full paragraph.

Similarly, you might adapt the amount of time that you give different children to complete tasks, to increase the level of difficulty.

Differentiation in teaching comes to the fore during periods of questioning. This could be as simple as considering which questions to pose to which children, or using open-ended questions to create challenge for children who already know a lot about what you are discussing.

4) Layer your language

There is a lot of focus on widening children’s vocabulary at the moment and this is an area where you can easily differentiate, by layering the language that you use.

When you are explaining something to your class, you will usually repeat information or instructions several times.

As you repeat them, incorporate synonyms for some of the words to increase the level of challenge. For instance, you might use the words ‘writing’, ‘text’ and ‘prose’ or ‘word’, ‘vocabulary’ and ‘terminology’.

5) Create three-column worksheets

When you create worksheets, a simple way to embed differentiation is to use the ‘three column method’. Divide the sheet into three columns, and put a series of questions in the middle column that are pitched roughly at the average of the class.

In the left-hand column put easier questions and in the right-hand column more-challenging ones.

Ask the children to try doing a couple of questions from the middle column before self-assessing their learning.

They should move to the left-hand column if they find the questions too hard or to the right-hand column if the questions are too easy.

6) Forms and perspectives

Another simple way to differentiate learning is to encourage the children to use different forms and perspectives in their writing.

Create challenge by asking them to come up with a recipe in the form of a poem, or to write a story from the perspective of the football in the World Cup final.

Add support by giving them frames and scaffolds or by offering them a word bank to use as they write.

Consider too when some children might benefit from putting their ideas down in a different format – for instance, with the teacher acting as scribe, or by recording a story rather than writing it.

7) Self-stretching

Wherever possible, get your children to think about their learning, and how they can stretch themselves. For example, instead of the classic spelling test, where everyone learns the same spellings, they could focus on the five words they find hardest and test themselves on these instead.

Although it’s not easy to personalise the learning to each individual, it is always useful to consider what the ‘next steps’ for each child might be.

Build your knowledge about the children in your class, so you can walk alongside them on the path to learning.

Differentiating for children with SEND

Differentiation in teaching should help prepare every child for their own, personal future, says Cheryl Drabble…

Whenever you move a child nearer to the IWB, make a wall display less busy and bright, or move a learner away from the window or some other kind of distraction, you are differentiating.

See also the use of visual timetables for autistic children, talking more slowly for a child with speech and language challenges and making bullet point lists for a child with dyslexia. All this is differentiation – teachers do it all day, and barely give it a thought.

How to do it

So how do we differentiate for each child and ensure they have the opportunity to achieve success at their own level?

“Teachers do it all day, and barely give it a thought”

Let’s take literacy. For some children, it involves studying different genres and improving their reading, writing spelling and grammar.

It’s about ensuring they possess enough knowledge to continue on to higher education, gain degrees and possibly add new knowledge to the world.

For other children, literacy is about becoming functional readers and writers who can hold down good jobs, buy their own houses and be independent adults.

Then there are some children who are in a different category. They may have SEND, or learning difficulties – either way, they will need a personalised literacy objective.

Example of differentiation for SEND

If we use the example of a non-fiction instruction book, the most able children in the class will be quickly writing their own manuals, using lists, directives and time connectives to illustrate their growing knowledge.

The children with SEND or a learning difficulty, on the other hand, could be working on instructions seen in the real world.

Their remit might be to follow instructions around a supermarket in order to find the fruit department. They would be looking for signs pointing to the trolleys, the fruit aisle and the cashiers and navigating via the store’s overhead displays.

This type of learning objective is incredibly relevant to the child, as we are skilling that child for their own personal future – one that won’t include them reading instruction manuals, but may well see them attempting to do their shopping independently.

These children want to be with their peers. They want to listen to the same books as their friends and experience, where possible, the same things. To deny them this opportunity is to exclude them while attempting to practice inclusion.

Keep your expectations high for all children. Remember – differentiation in teaching simply means ‘one size doesn’t fit all’. Include everyone in your basic lesson, and ensure your objectives are relevant to that child’s future.

Cheryl Drabble is acting assistant head at Highfurlong School in Blackpool. She is the author of Supporting Children with Special Educational Needs and Disabilities (Bloomsbury).

Edtech solutions to help with differentiation

- Socrative can help you lead whole-group questioning, ensuring that no students can disappear at the back of the class

- Use videos students can pause, rewind and watch again, untethering you from the front of the class and changing your role from ‘sage on the stage’ to ‘guide by the side’

- Use Showbie to collect assignments and provide more meaningful, powerful and less time-consuming forms of feedback, such as voice notes

- Use software to create dynamic seating plans that allow students to help peers who may be struggling and encourage rich conversations between students who are excelling

- Set personalised questions for computing and science lessons respectively with Smart Revise and Tassomai. These can help students to retain more knowledge over time and beat the forgetting curve

- Use the Post-It app for iOS and Android to collate handwritten student thoughts in a digital format

- Microsoft OneNote’s built-in Ink Math Assistant can help students solve handwritten maths problems, with an accompanying step-by-step guide to reaching the solution.

David Hillyard has been a secondary school teacher for 25 years and is now better known as ‘the Dave from Craig ‘n’ Dave. He supports thousands of schools, teachers and students with digital classroom resources.

Thanks to the following contributors for their help with this article:

Alex Quigley is an English teacher and director of learning and research and Huntington School. He is the author of The Confident Teacher.

Julie Price Grimshaw is a teacher, teacher trainer, and education consultant. She is the author of Self-Propelled Learning and Effective Teaching and has been involved in school inspections since 2001.