“This School is like a Prison, Miss”

A ‘zero tolerance’ approach to behaviour forced Holly Rigby out of one school – but the alternative is proving to be no picnic…

- by Holly Rigby

When the leadership of my previous school insisted we march the students around the school at the beginning of every half-term to ‘practise’ silent corridors, I knew I had to go.

In spite of pupils from Year 9 upwards gloriously refusing to follow the corridor directive, and my Year 10s subversively whispering to me that “this is like a prison, miss”, I was finding it increasingly difficult to shut my classroom door to the oppressive ‘zero tolerance’ environment that was developing around me.

Whilst I longed for lively discussions about what motivates learners, or how to plan for engagement when teaching challenging texts, I was instead treated to six weeks of CPD on how to ensure students pack up in silence.

Inspired by the infamous teacher training videos of American charter school pupils performing classroom routines with militaristic obedience, my school was developing its own back catalogue.

Each week we were treated to one of these videos as part of our training, such as being made to discuss the ‘good practice’ of a teacher who used the school’s escalating system of sanctions to make sure their students were sitting upright at all times.

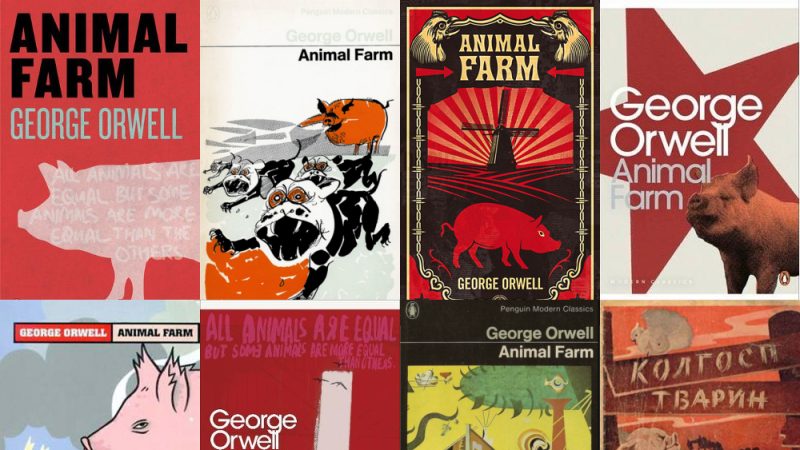

Pointing out that our English curriculum, stuffed full of dense 19th Century ‘canonical’ literature, might be one of the reasons that teens in my multicultural inner city school were falling asleep in lessons was not a welcomed intervention.

Classroom battleground

The prospect of joining my new school was therefore incredibly exciting; having immediately connected with its values of ‘humanity’ and ‘kindness’, I was eagerly anticipating finally teaching in an environment which aimed to develop reflective, critical young people, rather than obedient automatons.

It was something of a shock, therefore, when I found myself completely frazzled at the end of every day in my first half-term of joining the school.

My classroom had become a battleground unlike anything I’d experienced since becoming a beleaguered trainee teacher six years before.

A small part of this, of course, was the experience of joining a new place where I did not know the staff or student body.

But when confronted with the reality of young people who won’t immediately comply because they don’t have the sword of Damocles over-hanging them, I began to question whether I could thrive in this more tumultuous environment.

The reality is that for many schools a rigid, punitive behaviour system is the quickest route to a highly controlled atmosphere.

Whilst it may breed passivity and resentment for the majority of students, and exclusion for the rest, for overworked and underpaid teachers this kind of behaviour system is appealing to many because it is just more simple to manage.

The easy option?

Building relationships with students and creating a school culture that all students truly feel they are part of, rather than that it is something imposed on them, takes a high staff-to-learner ratio, considerable amounts of time, and specialised support for children who are struggling.

All of these things are in short supply in the current school funding climate.

It’s going to be easier for the government to spend £10 million on a behaviour taskforce that can implement its favoured zero tolerance behaviour policies, than it is to deal with poverty, the recruitment and retention crisis, and our impoverished teacher education routes, which may be the cause of challenging behaviour in the first place.

The school I currently work in doesn’t want to settle on what is ‘easy’ or ‘possible’ to achieve in the current system, valuing the development of student’s character and wellbeing over creating a ‘controlled’ environment.

This makes it an exciting place to teach and to learn; but we must not deny that encouraging schools to adopt this approach whilst the institutional and structural challenges facing them remain so daunting, is a tough ask.

Ultimately, until our schools are given the funding they need, and the families of our most disadvantaged students are on the receiving end of a significant redistribution of wealth, the contradictions involved in creating a calm, harmonious school culture will remain.

Holly Rigby is an English teacher and activist in the National Education Union Young Teachers Network. Follow her on Twitter at @hollyarigby and .