Teaching the British Empire – Why students deserve more than an incomplete history

Aneira Roose-McClew makes the case for why students ought to receive a full, frank and honest education on Britain’s imperial history…

- by Aneira Roose-McClew

- Senior curriculum developer at Facing History & Ourselves UK

Almost 2,500 years ago, the Greek philosopher Plato summarised the link between power and stories in a succinct and memorable phrase: ‘Those who tell the stories rule society.’

This relationship between the holders of power and their ability to influence or control the narrative is evident throughout modern society. It’s visible in the ability of media moguls to shape public opinion, in the billionaire-making social media industry to manipulate minds and elections.

It’s also relevant when we come to reflect on how our colonial history is perceived in present-day Great Britain. When it comes to colonialism, it’s as though the power holders and colonists of yesterday still control the narrative.

An incomplete history

The history we learn in educational institutions and wider society concerning the British Empire is incomplete. The stories that dominate tend to amplify the voices of the colonisers, depicting the ‘Imperial period’ as a time of glory and greatness – while the plunder, oppression and destruction of indigenous peoples, and their societies and cultures, often occupies, at most, a footnote.

We hear of how Britain’s Empire left behind sporting traditions, train networks, education and democracy (as if those subjected to colonialism wouldn’t have come to these themselves), but learn little of how much of Britain’s current wealth can be traced back to the suffering, exploitation and enslavement of millions of fellow human beings in overseas territories.

Nor do we learn of how the racist structures that persist today were colonial creations used to justify theft and oppression. Colonialism fuelled, and was fuelled by, racist beliefs; British people were said to be ‘civilising’ the ‘uncivilised’.

Learning an incomplete narrative like this creates a misguided sense of nostalgia. It’s not surprising that in times of difficulty and stagnation, tales of imperial glory have led many Britons to look backwards to a time, we’re told, that was full of wealth and prosperity, rather than forwards.

Imperial power and the slave trade

This warped understanding of the past stifles progress. It prevents us from taking the steps needed now to create a better society for all. Such nostalgia also highlights a lack of understanding about the impact of colonialism and our imperial history, which can hinder our ability to engage with our complex past with empathy and humility.

A March 2020 YouGov survey found that 33% of British respondents believed that countries colonised by Britain were ‘Better off overall’ for having been a British colony, whilst 32% were ‘Proud of the British Empire’.

It would be odd, if not sinister, to express these sentiments if those surveyed knew that the British Empire enslaved over 3.4 million people in Africa; oversaw famines in India in which millions starved; and amassed wealth by plundering countries around the globe. If the brutal realities of the colonial past of the British Government were taught in schools and discussed more within wider society, those survey results would no doubt be very different. As, indeed, might be our current political reality.

United Kingdom – The ‘mother’ country

This lack of education concerning British colonialism is further problematic in that it impedes our ability to tackle systemic racism. Without fully understanding the roots of the racist social structures that place white people above the rest, and which negatively impact the opportunities available to people of colour, we can’t challenge them.

Britain’s current social hierarchy is a product of colonialism, and the racial inequality of the present day can’t be divorced from this history. It’s a direct consequence of othering humans on account of their skin colour to justify shameful exploitation. Until we honestly examine this racist history and actively take steps to dismantle its structures, white voices will continue to be amplified, and white experiences still catered to by default.

Moreover, the failure to understand how Britain invaded other nations adds further fuel to racist attitudes that focus on individuals’ rights to be here. Too often, immigrants and Britons alike are accosted in the street and told to ‘Go back to where they came from’ because of their skin colour.

These racist views misunderstand how Britain’s colonial past paved the way for immigration to this island, thus shaping its present day demographics. For a period, Britain presented itself as the ‘mother’ country – extracting wealth, labour and military power from its colonies, while instigating relationships with the people who lived in them.

These relationships didn’t exist in a vacuum, nor did they stop when those colonies later gained independence. Ambalavaner Sivanandan, a former director of the Institute of Race Relations, summed this up well in a curt statement on postcolonial migration: ‘We are here because you were there’.

Honest engagement with British Imperialism

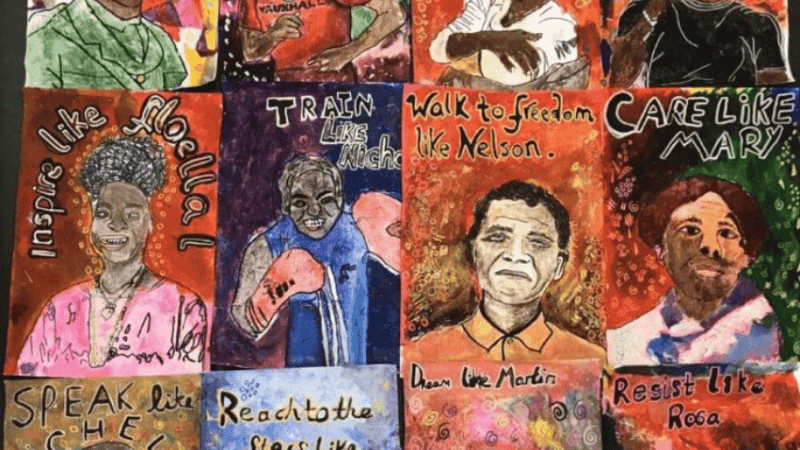

As educators, we need to start challenging the stories of Britain’s imperial greatness that have endured, despite the end of colonialism. We need to question whose perspectives are missing from the narrative and fill in the blanks. In short, as thousands of young people have called for in petitions up and down the country, we need to decolonise the curriculum.

Telling the full story about Britain’s painful and destructive history can help us challenge racist attitudes and systems, tackle social inequality and build a more empathetic society which would allow everyone, regardless of skin colour and class, to thrive. It’s an act of justice – one which seeks to ensure that we tell the stories of, and bear witness to, those who suffered.

At Facing History and Ourselves, we believe that decolonising the curriculum goes hand in hand with giving students the tools to become active, thoughtful, and responsible citizens who are able to engage critically with the world around them. Our collective history contains many lessons which can help guide our behaviour in the present.

To learn these lessons, we need to engage honestly with the past and explore how it’s both shaped the modern world and shaped who we are. To this end, we provide students with opportunities to engage with the complexities of identity, examine the range of human behaviour and reflect on the impact and consequences of our choices and actions. Once students understand the relationship between choices and history, they can better understand their own agency and the role they can play in standing up against injustice.

First steps to teaching British history today

1 | Overseas colonies and slavery

Before discussing challenging topics with students, like slavery, war, British colonial rule and imperial expansion, connect with yourself – your identity and experiences – and reflect on how who you are might impact upon your interactions with students and how you engage with certain topics.

2 | British Rule – Make your classroom a safe and brave space

Use contracting to build a classroom environment in which students can share their ideas and experiences, and practice disagreeing respectfully.

3 | Decolonisation of content

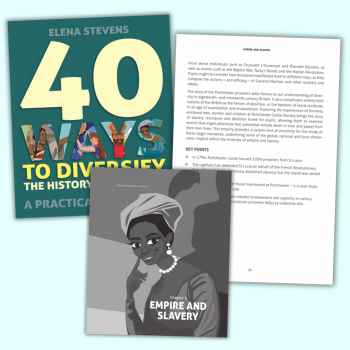

Spend time reflecting on the content that you share with students. Think about whose stories it tells and whose perspectives it’s missing, and actively seek out other narratives. When voices are missing, acknowledge this and explore why that might be the case.

Aneira Roose-McClew is former secondary teacher, examiner and teacher trainer, and now content developer at Facing History & Ourselves UK – a charity that uses lessons from history to challenge teachers and their students to stand up to bigotry and hate; find out more by visiting facinghistory.org/uk or following @FacingHistoryUK.