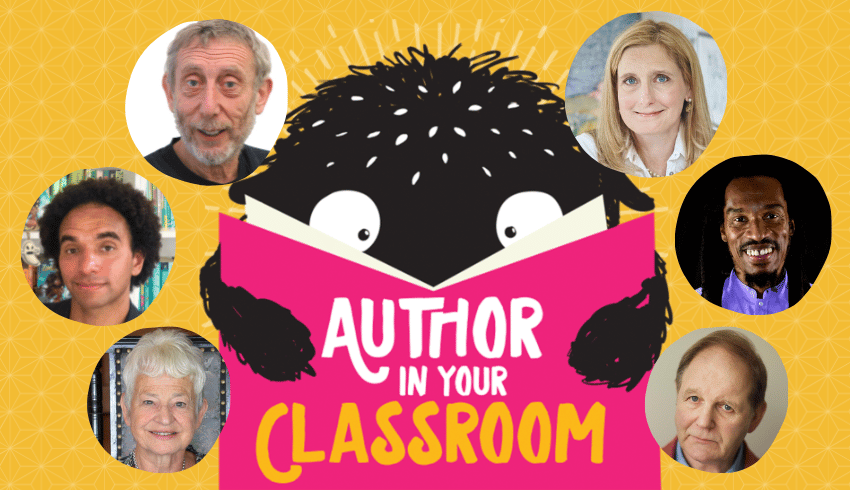

Children’s authors – Free KS2 virtual visit & resources with Michael Rosen, Jacqueline Wilson & more…

Bring best-selling children’s authors into your classroom for free with a podcast and accompanying resources…

Do you ever wish that you could just halaund over your English lesson to one of the UK’s most successful children’s authors and let them take the reins? Do you think your pupils would be inspired by hearing directly from popular children’s authors about how they go about their writing?

You’re in luck! Author In Your Classroom is a brilliant free podcast series recorded especially for schools.

JUMP TO AN AUTHOR

- Sir Michael Morpurgo

- Dame Jacqueline Wilson

- Michael Rosen

- Joseph Coelho

- Lauren Child

- Frank Cottrell-Boyce

- Benjamin Zephaniah

- Cressida Cowell

- Robin Stevens

- Liz Pichon

Free writing resources

Every episode of Author In Your Classroom comes with free:

- Teacher notes

- PowerPoints

- Planning grids

- Writing sheets

- Quotes and illustrations for display

There are more than 25 episodes to choose from so far, with some of the most famous children’s authors the UK has to offer.

So if you’ve got the next Enid Blyton or Beatrix Potter on your hands, or pupils who are desperate to pen the next Harry Potter or Alex Rider, give it a go in your classroom today.

Just search for Author In Your Classroom wherever you listen to podcasts, and be sure to hit ‘subscribe’ so you never miss an episode.

Let’s take a closer look at ten of the episodes on offer…

1 Write a new take on a classic with Sir Michael Morpurgo

Having authored classic books such as War Horse, The Butterfly Lion and Private Peaceful, Sir Michael Morpurgo is one of the undisputed champions of children’s literature.

In this episode, Sir Michael ponders why, in a world with unlimited numbers of stories, we are so keen to repeat the same ones.

“A story always comes from a truth; from something that is real”

Sir Michael Morpurgo

For young writers, adding their own ideas to a well-known story can be a motivating and enriching writing activity. A familiar tale can provide the characters or narrative structure, allowing children to use their imaginations to create something new and different.

Who better to learn about this idea from than Sir Michael Morpurgo, one of the world’s most beloved children’s authors?

The free accompanying resources allow children to learn from Michael’s experience and wisdom. They’ll draw inspiration from his book Boy Giant. This wonderful novel combines a retelling of Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels with the story of Omar, a young refugee fleeing war in Afghanistan.

Children will have the chance to take a classic story that they know well and combine it with an issue they feel passionate about to create their own story built on a truth.

Activity suggestion

- Work in pairs or small groups to think of important issues that are affecting the world today that could form the idea at the centre of a story. Record these on Planning Sheet 1.

- On Planning Sheet 2, jot down the names of some classic stories.

- Look at the two planning sheets and discuss if any of the stories match one of the important issues. For example, wicked stepsisters could be good for a story about online bullying, or a story set in the forest could be an interesting way to talk about deforestation.

- Use Planning Sheet 3 to plan a story, then share ideas in partners or groups.

There are lots more writing ideas and activities in the podcast and accompanying resource pack.

Writing advice from Michael Morpurgo

“Generally speaking, you start by thinking you can only write about what’s in front of you. So when I was a teacher, my stories were either about the lives of our own children at home, or the children I was teaching at school.

“As I’ve got older I’ve known lots of joys and sadnesses and I see the world more for what it is, rather than what I hoped it might be. I write about things that are, I suppose, more complex. And so I’ve grown as a writer.”

2 Place familiar characters in new settings with Dame Jacqueline Wilson

Much-loved author and former children’s laureate Dame Jacqueline Wilson has written over 100 books that have been enjoyed by children and adults alike.

Some of her unique characters have been turned into popular children’s television shows, with audiences sharing the lives of Tracy Beaker and Hetty Feather.

In this episode, Jacqueline talks about her book The Primrose Railway Children and placing characters from one story into new surroundings.

“The beginning of being a writer is making things up”

Dame Jacqueline Wilson

In The Primrose Railway Children, Phoebe narrates the story of her family’s move to the countryside in mysterious circumstances. They discover an Edwardian railway line, the Primrose Railway, and enjoy rides on the classic steam trains.

The book is based on E Nesbitt’s classic The Railway Children, reimagining the story for modern children.

Use the accompanying resources to explore how characters might react to the new places that they visit, then write stories based on children’s own ideas.

Activity suggestion

- Think about characters in stories you’ve read. Create a list as a class.

- Consider how you might change the characters in some way for a new story. You could change the time that they are alive, their names, gender or something else. Remember that the essence or characteristics should remain similar.

- Discuss new places that characters could visit, and create a list as a class. It could be somewhere like the Primrose Railway, that shows how things were in the past. Or characters could move from the city to the countryside or vice versa.

- Discuss your characters and new places in pairs or small groups. Use role play to develop the character further by describing the unfamiliar places while in character.

Find lots more inspiring ideas and activities in the resource pack.

Writing advice from Jacqueline Wilson

“I remember when I was young and writing my own stories, I would get stuck after about five or six pages. I’d get a bit bored with the story and not really want to continue.

“I feel that as long as it’s not for school, does it matter if you don’t finish it? No, it doesn’t. Childhood is the one time in your life when you can just purely write for fun and just enjoy it. That’s what’s important.

“When you’re doing something for school you have to think of a good beginning and ending and you have to make notes beforehand. You have to try to use correct grammar and remember all your commas and full stops.

“When you’re writing for yourself it’s good to remember all these things, but just write what’s in your head. Don’t necessarily plan ahead – surprise yourself!”

3 Dream up a poem with Michael Rosen

How do children’s authors get their ideas for writing? Daydreaming can be an important part of it.

Spending time thinking about a topic, linking it to your personal experiences and allowing your mind to wander can generate fantastic ideas for stories and poems.

In Michael Rosen’s episode of Author In Your Classroom, the beloved poet and award-winning author shares some of his best writing tips and poetic techniques.

He also talks about his collection of poetry, On the Move, and why the topic of migration is so powerful for him.

“If I concentrate on a moment, I can find ways of writing about it by going to the ‘shop of ideas’”

Michael Rosen

On the Move is divided into four sections. In the first, Michael Rosen draws on his own childhood. He focuses on his perception of the war as a young boy in the second part. In the third, he explores his “missing” relatives and the Holocaust; and in the fourth, on global experiences of migration.

Using the free accompanying resources, children will have the chance to write poems based on their daydreams and personal experiences.

Activity suggestion

- Spend a minute daydreaming about your chosen idea for writing, then jot down your thoughts on the planning sheet. These can be words or phrases. Create offshoots on the diagram to link ideas.

- Think about whether any of these ideas are linked to your own personal experiences. Add further ideas to the planning sheet.

- Explore metaphors, similes and personification and think about how you could use figurative language to describe some of the ideas from the planning sheet, then write your own poem.

Browse lots more great classroom ideas in the resource pack.

Writing advice from Michael Rosen

“We think of school as being a busy place but daydreaming is very good because you go into your own mind.

“Shut your eyes – I find that helps – then sit for maybe ten seconds or even a minute and daydream. When you come out of the daydream, jot down some notes.

“You don’t have to write in sentences – just single words or phrases. This page of scribbles is food for your writing. Take any of those ideas and play with them.”

4 Create imagery in poetry with Joseph Coelho

In this Author In Your Classroom episode, Children’s Laureate Joseph Coelho explains his early writing experiences, how he collects ideas and how he uses the many poetry tools available to him when writing his poems. He also shares how people can recognise a poem and how this differs from prose.

“I want to see more and more children and adults seeing poetry as something they can do”

Joseph Coelho

He reads his poem This Bear, taken from his poetry collection Poems Aloud: An Anthology of Poems to be Read Aloud and talks about how, in this collection of poems, he gives suggestions for how the poem should be read.

Use our free resources to read and explore Joseph’s poem This Bear, then investigate the figurative language that Coelho has used from his ‘poetry toolbox’.

Activity suggestion

- Discuss different examples of figurative language and other tools that can be used when writing poetry using the posters provided in the resource pack.

- Annotate a copy of the poem This Bear (Worksheet 2) to show the tools Joseph Coelho has used.

- Explore the Poetry Prompts Library that Joseph is creating with the Book Trust to inspire everyone to write poetry.

- Choose one prompt to focus on. Use Planning Sheet 1 to jot down ideas for a poem based on the chosen prompt, then go ahead and write it.

There are a lot more activity ideas in the resource pack.

Writing advice from Joseph Coelho

“I tend to think that writer’s block doesn’t really exist. I think what happens is we fail to take note of our ideas when they arrive.

“It’s very easy to remedy that. You need to keep a notebook with you at all times. We all have brilliant ideas but they just come at weird times – in the middle of the night, first thing in the morning, on your way to or from school, during lunch break or playtime.

“But If you’ve got a little notebook and a little pencil with you you can note down those ideas – it might be a word, a sentence, the idea for a poem or a story or a turn of phrase.

“When I come to sit at my computer, if I’m stuck for ideas I can turn to my notebook and look through all the different ideas I’ve had over the last few days, weeks, months, years even.”

5 Imagine a cast of characters with Lauren Child

Characters are vital when creating great stories. They guide the reader through their journey and great children’s authors give us more information about their fantastic characters along the way.

Children’s author and illustrator Lauren Child has created many ‘larger than life’ characters, such as Charlie and Lola and Clarice Bean.

She’s also reimagined the classic character of Pippi Longstocking by Astrid Lindgren. In Pippi Longstocking Goes Aboard, Lauren brings Pippi’s character and enthusiasm for life alive on the page.

“A little thought could be the beginning of a big idea”

Lauren Child

In this episode, Lauren spends an uplifting half an hour discussing her characters, the challenge of illustrating other people’s words, and how to spot a good idea when one comes along.

Use the exclusive free resources to help pupils create their own characters and illustrations while thinking about their back story.

Children will need to notice small things that they can combine to create ideas for a story using some of their newly-created characters, either bringing them into Pippi’s world or writing their own stories.

Activity suggestion

- Use Planning Sheet 1 to jot down ideas for a new cast of characters that could be used in a story.

- Discuss character ideas with friends and note down any extra ideas you have.

- Choose one character to develop further. Use Planning Sheet 2 to create a profile of them. Add rough illustrations that show the character’s personality.

- Sit for a moment or two and look and listen to what is going on around you. Create a class list of things that people noticed. Build upon these ideas to create a story.

Browse plenty more ideas to go alongside the podcast in the resource pack.

Writing advice from Lauren Child

“I write stories over years and decades. I have these little fragments of stories – some are nearly finished, some are in their early stages. And I gradually, gradually get to them.

“Some of them I look at and think, ‘Oh my goodness, no! What were you thinking of?’. But some I keep returning to. And they change, then change into something else. And then, finally, I find the story in it.”

6 Explore weird facts with Frank Cottrell-Boyce

Many weird and wonderful facts seem impossible – but are, in fact, actually true. In this episode, the children’s author Frank Cottrell-Boyce takes pupils on a journey of adventure and mystery with his book Noah’s Gold.

“There is something in your head that might never have been in anyone else’s head!”

Frank Cottrell-Boyce

Throughout the story, Frank sensitively and humorously explores how our unquestioning reliance on technology can weaken our mind and survival skills – and wonders whether perhaps we should sometimes leave our mobile phones switched off…

Explore the free resources pack to help pupils write stories of their own, based on a weird and wonderful fact.

Activity suggestion

- Think about any weird and wonderful facts that you know. Create a class list of suggestions.

- On Planning Sheet 1, jot down your favourite facts, then develop one further using Planning Sheet 2. Make a note of events that could link to the fact. Think of as many ideas as you can.

- Plan your own funny short story based on your weird and wonderful fact, thinking of a problem and how it might be solved.

Browse all the classroom ideas by downloading the resource pack.

Writing advice from Frank Cottrell-Boyce

“People always ask writers where their ideas come from. The real truth is that ideas come when you start. You only need just enough of an idea to start. And as soon as you start writing, other ideas start to come.

“Begin the journey – you might end up somewhere else completely but you just need the courage to start writing. Once you get going, you’ll have better ideas.”

7 Find your voice with Benjamin Zephaniah

There’s nothing quite like that sensation when you settle down to read a book and a character speaks to you so clearly that it’s like they’re there in the room with you.

You’re there sharing their adventures, seeing the world through their eyes, feeling what they feel.

Through a great story, we can see ourselves and our own experiences mirrored back to us. Stories for children can also act as a window, giving us the chance to look into another world or see things from the perspective of a character very different from us.

“If you don’t write your story… somebody will write it for you”

Benjamin Zephaniah

It takes skill to write like this, but although tricky to master, it can be a hugely motivating and rewarding skill to explore in the classroom with young writers.

Of the many children’s authors we might turn to for inspiration for this aspect of writing, few came more highly qualified than the much-missed poet and author Benjamin Zephaniah.

In this episode, Benjamin explained how and why he writes and discusses the historical truth behind his novel, Windrush Child. He also shared powerful advice for pupils who struggle to find their voice and make it heard.

Use the free resources pack to encourage pupils to write their own stories featuring a powerful voice – either their own or in role as a character from history.

Activity suggestion

- Think about a story from your own life that would be good to tell – it can be something small or big, funny or dramatic. Jot down ideas on Planning Sheet 1.

- Now think about if there are any stories from history that you’d like to tell. This could be because you know lots about a particular period or think there is a good lesson to be learnt. Use Planning Sheet 2 to make a note of ideas. Think about who would narrate the story – someone who was affected by the event works best. Share your research in groups or as a class.

- Choose either Plan 1 or Plan 2 and write your own first-person story with a strong narrative voice.

Find lots more details and other ideas in the downloadable resource pack.

Writing advice from Benjamin Zephaniah

“What people don’t realise is you never get it right first time. Writing is not about writing – it’s about rewriting. Even when you’ve done that you need a good editor. The best writers in the world have the best editors in the world.

“A good editor can read one of my publications like they’re seven years old, then like they’re 50 years old. It’s an amazing talent and one that I don’t have.”

8 Create magical creatures with Cressida Cowell

Former Children’s Laureate and legendary children’s author Cressida Cowell is the creator of the beloved How to Train Your Dragon series. Her captivating The Wizards of Once books are also full of magical creatures that will terrify and delight children (often both at the same time!).

“It’s not about your handwriting or your spelling, and it’s not a race – it’s about your ideas”

Cressida Cowell

There are few challenges more motivating and exciting than creating brand-new magical creatures and then writing about them. As a task, it allows children to use their imagination and think creatively, with the added bonus that there’s no way they can get it wrong.

This episode, and the accompanying resources, are the perfect way to engage young writers, especially those who perhaps feel that writing isn’t for them.

Use the free accompanying resource pack to give children the chance to create a new magical creature and then write a scene from a story featuring their invention, learning from Cressida Cowell herself.

Activity suggestion

- Explain to pupils that just like Cressida, they’re going to use their real experiences, research and their imagination to invent a brand-new magical creature.

- Use books or the internet to research real interesting creatures and record the details on Planning Sheet 1.

- Next, use Planning Sheet 2 to draw your creature and record your ideas.

- Use Planning Sheet 3 to collect language and ideas to describe the creature.

- Invent some examples of indirect description for your create and record these on Planning Sheet 4.

- Use the planning sheets to help you write a short description of your magical creature, including carefully chosen adjectives, verbs and adverbs for description, similes, metaphors and indirect description.

Find lots more advice and extra activity ideas in the resource pack.

Writing advice from Cressida Cowell

“Writing is like telling a really big lie. The more detail you put in, and the more you base it on a grain of truth, the more it comes alive in your reader’s head.

“If I say my character had a big red beard, can you see the beard in your head? Sort of.

“But if I say Gob had a beard like exploding fireworks or a hedgehog struck by lightning, you can see the beard a bit more clearly because I’ve based it on something true.”

9 Plan a plot with Robin Stevens

An important aspect of great story writing is planning a plot. This is something children at primary school can find tricky.

“If it’s not enhancing the plot, it’s just dead words – even if they’re beautiful”

Robin Stevens

A story can easily end up being a list of things that happen to the main character, rather than a real narrative with a beginning, middle and end.

Luckily, Robin Stevens, author of the award-winning Murder Most Unladylike series is on hand in this episode to offer tips and advice for planning a brilliant plot. Use the free resource pack to help KS2 pupils write their own mystery story.

Activity suggestion

- Work in pairs using Planning Sheet 1 to dream up a new detective character for a mystery story.

- Next, devise some possible settings for your story that fit the detective you’ve created.

- Now think about some different crimes and victims that link to this setting. Share ideas with a partner or in small groups.

- Plan who the suspects will be and what clues might incriminate them, then devise a resolution for the story, focusing on trying to surprise the reader.

- Conclude by writing a mystery story from the perspective of the detective, using all of your previous planning to help.

Find lots more ideas and advice in the podcast and resource pack.

Writing advice from Robin Stevens

“I have days where I feel like I don’t have much inspiration. On other days I’m desperate to write and the words flow out of me.

“I do think it’s important for me to keep going on days that I don’t feel wildly inspired, because a lot of writing is about getting the words out. Then you can go back and make them better later.”

10 Create a supervillain with Liz Pichon

There have been many supervillains in both stories and films – think of the Child Catcher, Bond villains and Voldemort, to name a few. Writers have always created fantastic baddies that we both love and despise.

In this episode of Author in Your Classroom, Liz Pichon discusses her book Shoe Wars. It’s a hilarious story that was inspired by a real falling out between two brothers who made shoes.

“The good thing about villains is that they are great fun to write about”

Liz Pichon

Liz discusses where her ideas for stories come from and why it is so much fun creating villains and the story world that they live in.

Inspired by Liz, give children the chance to collect ideas that they could use to write stories and create their own supervillains.

Use the free resource pack to explore the writing techniques that Liz Pichon uses in the extract from the book that she reads in the podcast, then create your own descriptions of a villain entering a scene.

Activity suggestion

- Use Planning Sheet 1 to jot down ideas for stories. Include things you remember from conversations, things that have happened to you or things that interest you.

- Discuss your story ideas with peers. Are there any that are worth combining to create a great story idea?

- Think about how you can include a villain in your story. Use Planning Sheet 2 to draw them. Add information about how they behave and why.

- Write a scene showing a supervillain making an entrance. Use writing techniques such as alliteration, expanded noun phrases, similes and dialogue.

Writing advice from Liz Pichon

“Get yourself a little notebook. Write things in there and stick pictures in, otherwise it’s so easy to forget your ideas.

“If one of your friends says something funny to you, write it down. If somebody’s got a funny name or you see a funny picture, write it down.

“Those are the things that you can go back to and that might help you to tell a story later on. I do that all the time because I’ve got a terrible memory.”

Author visits to schools

Listening to Author In Your Classroom, and using the accompanying free resources, is like having children’s authors visiting your classroom, but without any of the hassle.

Because the podcast is free, there are also great savings to be made – especially since it can cost anywhere between £400-£750 on average to arrange for children’s authors to visit your school.

Whether you’re looking for special World Book Day activities, something for Children’s Book Week, or you simply want to make the podcast a weekly activity in your classroom, Author In Your Classroom is an excellent alternative if you’re on a budget.