How to Teach Storycraft in Secondary English

With the right tools, tricks and strategies, every learner can improve their creative writing skills, insist Jon Mayhew and Martin Griffin…

- by Teachwire

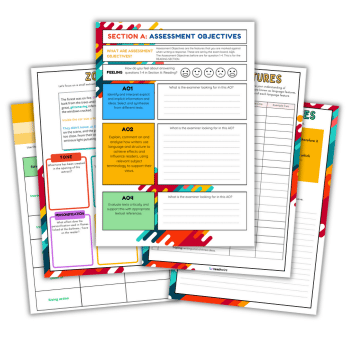

Download a free resource to support some of the ideas in this feature here.

If you have to write a short story quickly and you don’t have time to create a whole world, set your tale during a well-known historical event.

A smug con man tricks his way into a first-class cabin on board the Titanic. Two brothers argue in the trenches of the Somme.

This is just one of the many ways in which we get students to spark ideas for their stories and that are featured in our new book Storycraft: How to Teach Narrative Writing.

We both remember when Storycraft was born. We were sharing our recent experiences over a cup of steaming coffee, and a common theme emerged: the GCSE English language exam.

Delivering writing workshops in schools all over the country, we noticed a spike in the number of requests for creative writing sessions with GCSE groups emphasising quick generation of ideas, encouraging confidence in creativity and preparing students for the demands of narrative writing in the exam.

Teachers were reporting that many students felt anxious about having the skills or the imagination to write a creative piece in 45 minutes. Or were producing uninspiring, low scoring, work.

Finding the words

It struck us that, as experienced teachers and professional writers who had spent hours working closely with editors to craft award-winning novels, working to a deadline and constantly seeking to innovate, we were uniquely placed to create a resource that was of practical value to teachers and students alike.

Storycraftfocuses on getting students writing – putting words and ideas on paper as regularly and confidently as possible.

We picked fifty activities from our own workshop practice that get students crafting narratives regularly, more quickly and with gradually greater confidence.

We also explored the creative process in order to normalise the struggles associated with crafting something from nothing.

We wrote it with a year 11 class in mind but quickly realised that it was a set of tools, tricks and strategies that could be used at any level, be it at KS3 or with A Level students.

The creative process

Experience told us that students cleave to a variety of myths about writing and being a creator; from, ‘I haven’t got any ideas,’ through to ‘you can’t revise for this exam so I can just kick back and see what happens.’

We quickly decided that teachers could debunk these and many more misconceptions by addressing them overtly and providing activities that would give the students the material they need to do their job.

We codify the process that fosters creativity using the acronym, FORGE. This emphasises that good creative thinking requires:

- Feeding: Providing the imagination with fuel through reading, consuming stories, discussion and debate.

Once the material has been forged, it can be crafted into a satisfying form. This process doesn’t have to wait until GCSE, it can begin in Year 7.

The longer the students practise playing with ideas and taking risks, the more confident they will become; sharing the following activities will not only lead to immediate improvements in their writing, but will also help learners to build up a portfolio of storytelling elements on which they can draw any time they are asked to produce a narrative under pressure, including exam conditions.

1 | Characters

You can make up characters to populate your story before you ever set foot in an exam hall. They don’t have to be completely drawn but you should have some major details noted about them. Any characters you create should be flexible.

Don’t dismiss an old lady just because you’ve been asked to write about space travel; she’s unusual, and will make your story interesting; you wouldn’t expect an elderly woman with a knitting habit to be on a dangerous space mission, after all.

- Appearance

Think about what your character looks like. Note down three points about their appearance. Choose a special item of clothing – a hat, gloves or a coat. Give your character a tic, a habit or a catch-phrase. - Wants/needs

Make a note of what your character wants to achieve. This could be minor eg: to finish a jumper she is knitting for her grand-daughter, through to something major, more emotional eg: to forget the death of her husband. Your want or need could be quite innocent to begin with but then you can twist it. What if the knitting space old lady wants to forget the death of her husband because she murdered him? - Create a twist

My old lady might not reveal that she has killed her husband until the last sentence. This will shock the reader and change his or her view of the character. And my old lady who killed her husband could be clicking away on her knitting needles in a spaceship, on a bus or a haunted house. She could travel back in time or go on a safari.

2 | Mood and imagery

Just as with characters, you can prefabricate some imagery for your story and memorise it.

Again, you may have to adapt some of your ideas once you see the exam question, and you shouldn’t force something to fit into a story when it doesn’t really work, but this kind of preparation can cut down thinking time.

Decide on some mood colours and some similes and metaphors to go with them. Write them down and learn them.

3 | Settings

Revise some major historical events that you could use as a setting (remember, though, if you use the Titanic as the setting for your story, readers will know how it’s likely to end).

Revise a song, a mode of transport and a fashion item for each decade of the 20th century and for each quarter of the 17th, 18th and 19th century. This is a great way of instantly adding a dash of historical realism to your writing.

If you must make up an alien world, focus on three or four details eg: sky colour, multiple moons, strange coloured plants. If you’re going to have aliens, make them humanoid or like some kind of creature on Earth; that way you can describe by comparison.

4 | Inversions

Come up with some inversions and add them to your archive of creative writing elements for future use. This may be a character, eg: the friendly vampire or the crooked policeman. Or it could be a setting such as a horror funfair, a deadly school or a hospital where people are killed.

Martin Griffin has taught in 6th form colleges and the 11-18 sector. He’s been a head of English and deputy head teacher. Jon Mayhew has taught English, been a Senco in a wide variety of schools, and written many children’s books. They are the authors of Storycraft: How To Teach Narrative Writing (Crown House), which is due to be published in August 2019 (storycraftbook.com). Download our AQA English Language Paper 1 ultimate revision booklet.