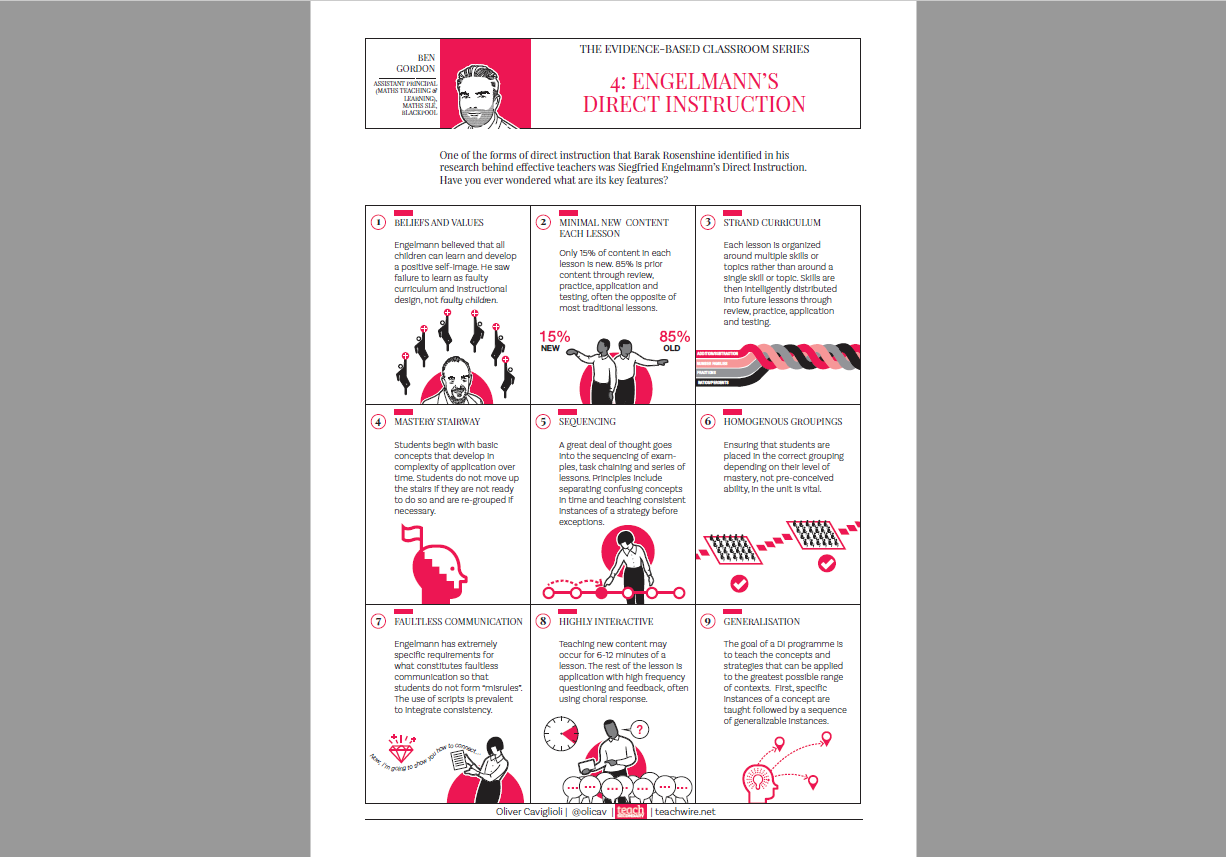

PDF poster

KS3, KS4

Years 7-11

Find out all about direct instruction in teaching and download a CPD poster for your staffroom covering nine of its key features…

What is direct instruction in teaching?

Direct instruction focuses on the expert transferring knowledge to the novice.

Siegfried Engelmann developed the first type of Direct Instruction (with capitals). It concentrates on the idea that we should build teaching on well-developed, careful planning.

Teachers should break down learning into small chunks consisting of clearly defined and prescribed learning tasks.

Barak Rosenshine introduced the second type of direct instruction (lowercase) in the late 70s. He used the term ‘direct instruction’ for an approach to teaching that led to optimal learning known as the Principles of Instruction. These continue to serve as the basis for the pedagogical approach in many schools.

Benefits

A huge misconception about direct instruction is that it makes learning boring. In actual fact, direct instruction has positive effects on learners in terms of progress and wellbeing.

Parents are more positive about it, teachers feel more confident using it and researchers have shown that it has a positive effect on learner attitudes, confidence and behaviour.

When it works well, direct instruction provides students with a highly interactive learning experience, built on a theoretical framework based on evidence-informed practice that includes superb examples of explanations, reducing cognitive load, sequencing of content, high success rates, interleaving and distributed practice.

Why don’t more schools use direct instruction?

Despite research clearly showing Direct Instruction to be more effective than other educational programmes, it is still not very widely used in schools.

If we look at the history of education in the 20th century, Engelmann’s ideology had some heavy opposition through Piaget, Bronte and others, who were selling a more naturalistic, progressive ideology of learning.

Engelmann’s highly structured programmes were seen as inferior to these naturalistic views, which were based on students learning things like speech and facial recognition very readily through social interactions. The education system believed that this was the way forward in the classroom.

However, ‘biologically primary’ learning is natural and mostly effortless – learning your mother tongue, for example, come naturally from social situations and constant exposure.

‘Biologically secondary’ learning, in contrast, is effortful and unnatural – such as decoding text and maths.

Most of the subject content that we want students to learn in school is biologically secondary, un-naturalistic and sometimes abstract, which requires expert teaching and instruction to help form concepts and understanding over time.

Alternative to DI

Discovery learning is a technique of inquiry-based learning that’s often classed as a ‘constructivist’ approach to education.

It’s an approach that utilises exploration; student aren’t provided with exact answers, but are instead given the materials they’ll need to find the answers.

In some contexts, the power of discovery can be a hugely motivational addition to a lesson. When used in conjunction with elements of DI, learners can build incredibly strong schema.

Thanks to Adam Riches and Ben Gordon for their help with this article. Adam Riches is a senior leader for teaching and learning. Ben Gordon is an assistant principal.

Engelmann’s Direct Instruction CPD poster

Our direct instruction poster, by information designer Oliver Caviglioli, covers the following key features of direct instruction:

- Beliefs and values

- Minimal new content each lesson

- Strand curriculum

- Mastery stairway

- Sequencing

- Homogenous groupings

- Faultless communication

- Highly interactive

- Generalisation