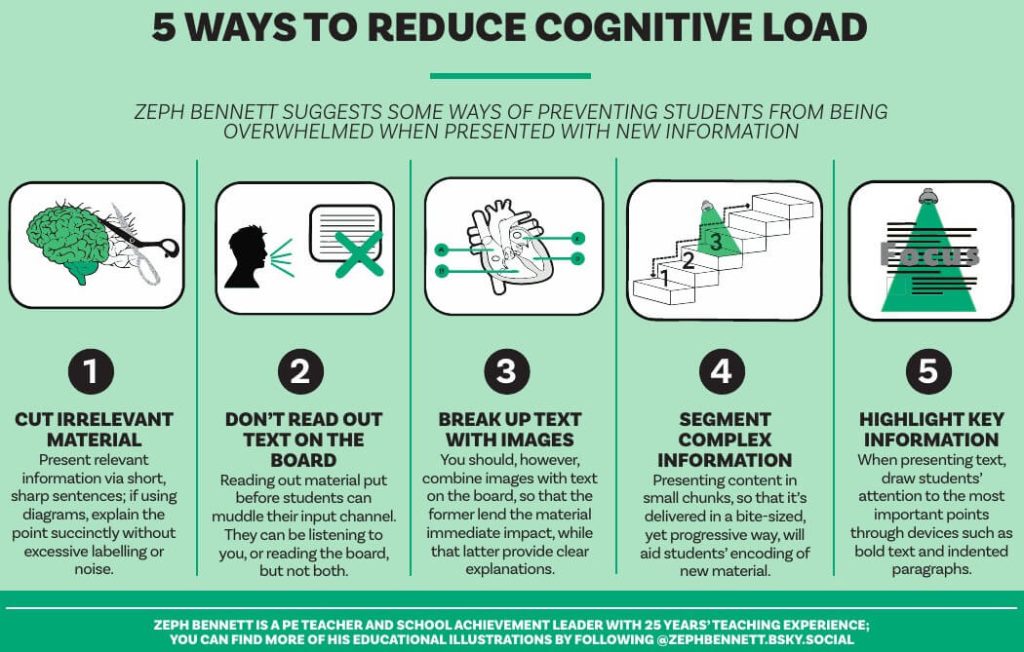

Join us as we explore cognitive load theory – a powerful framework that can help you design lessons that maximise learning by reducing unnecessary mental effort…

What is cognitive load theory?

Cognitive load theory is based around the idea that our working memory can only deal with a limited amount of information at any one time.

It focuses on the significance of how our brains deal with stimulus or inputs. It explains how to feed new information to learners in a way that enables them to process it, without being overburdened.

Who came up with the theory?

Australian educational psychologist John Sweller developed cognitive load theory in the late 1980s.

Sweller identified three types of cognitive load:

- intrinsic – the inherent difficulty of the material itself

- extraneous – ways of presenting the material that don’t aid learning

- germane – elements that actually aid information processing and contribute to the development of ‘schemas’

Sweller’s papers highlight what happens when we overload our working memory and the impact this can have on the completion of tasks, as well as the transfer of information from our short-term, finite working memory to our theoretically infinite long-term memory.

Cognitive load theory allows us to understand how our brains work in layman’s terms. Sweller’s papers do a great job of explaining learning from a psychological point of view, in a way that non-specialist classroom practitioners can easily grasp.

Practitioners versed in the theory will make active decisions when planning to ensure they don’t overload learners with unnecessary inputs and stimulus that may overburden them.

Adam Riches is a senior leader for teaching and learning; follow him at @teachmrriches.

Cognitive load theory’s role in curriculum sequencing

Cognitive load theory informs curriculum sequencing by revealing the role of memory in helping students build the cognitive architecture required to access the curriculum effectively.

As working memory is limited, we need to sequence our curriculum to reduce cognitive load. This can be done by drawing on prior knowledge and logically sequencing episodes of learning so they accumulate in small stages.

It’s about securing understanding at one stage before moving on to the next.

This assists in reducing cognitive load as students can draw more effectively from their long-term memory. This therefore reduces the load for their working memory.

Although activating prior knowledge is an effective method for reducing cognitive load, this needs always to serve new learning.

- Break down subject content when introducing new topics and make time to recap and recall information.

- Present instructions clearly without introducing too much information at the same time.

- Be wary of reducing cognitive load too much – you don’t want the desirable difficulty to be too low.

Classroom example

Take, for example, the idea of introducing the concept of colonialism through a study of the British Empire. Students need to access a working definition of ‘empire’, relying on their understanding of vocabulary such as ‘monarchy’ and ‘reign’.

You provide an explanation of imperialism, with a brief allusion to your previous teaching of Russia the year before. This is polished off with the image of Queen Victoria’s statue that displays the words ‘The entitlement of Great Britain’ underneath.

In this example, prior knowledge functions as extraneous load. Students are left grappling with their working definitions of key terms and their recognition of Queen Victoria. This is alongside a plethora of completely new information.

It’s made even more complicated by your attempts to draw prior knowledge from pupils with very little context.

Retrieval tasks

However, you could instead open the lesson with a retrieval task that prompts students to recall the definitions of ‘empire,’ ‘monarchy’ and ‘reign’.

You can then frame these within the context of the lesson. This makes explicit the connection between Queen Victoria and the British Empire’s role in widespread colonisation.

This way, you’re managing cognitive load and the activation of prior knowledge is purposeful for the lesson.

This results in your delivery being far more cohesive and ensures one idea connects to and informs the next.

Whilst careful sequencing can support new learning by exposing its relationship to prior knowledge, we need to ensure its activation does not contribute to extraneous load.

When sequencing learning we need to judiciously select the knowledge most likely to support and connect to new learning. This is so that we don’t unintentionally hinder students’ understanding.

This requires a systematic, streamlined approach to the activation of prior knowledge with explicit connections between what has been learnt and what is to come next.

This is so that these connections strengthen students’ cognitive architecture, rather than act as an extraneous distraction.

Kat Howard (@SaysMiss) is a senior leader at the Duston School, Northamptonshire. Claire Hill (@Claire_Hill_) is trust vice principal and secondary improvement lead at Turner Schools in Kent. They are authors of Symbiosis: the Curriculum and the Classroom (John Catt).

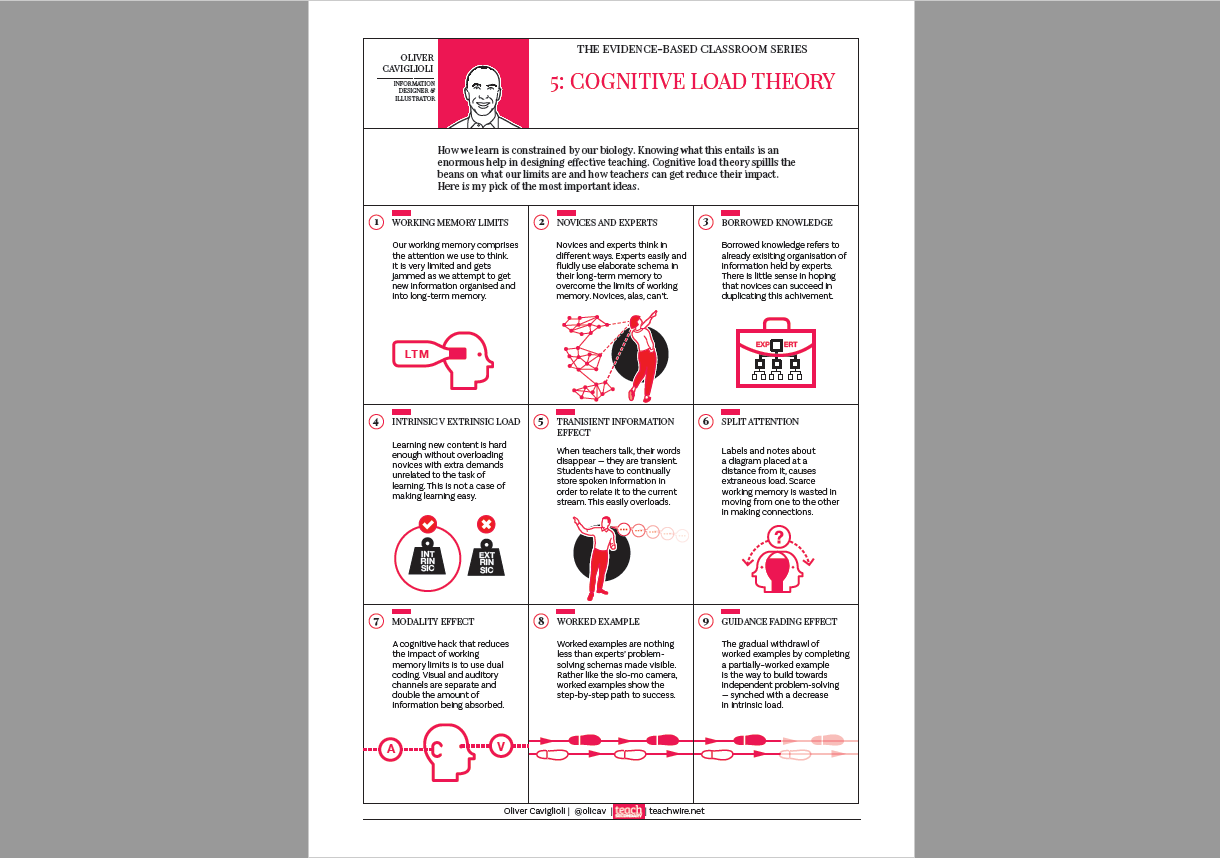

Staffroom poster

Our free poster (available to download at the top of this page) sets out nine important components of cognitive load theory. These are:

- Working memory limits

- Novices and experts

- Borrowed knowledge

- Intrinsic vs extrinsic load

- Transient information effect

- Split attention

- Modality effect

- Worked example

- Guidance fading effect

The poster was designed by Oliver Caviglioli. Find him at olicav.com and follow him on X at @olicav. Take a look at another of Oliver’s CPD posters.