Creating Books for Children Lets you say Important Things to Them – and their Parents

Creating books for children offers an unrivalled opportunity to say important things to them – and to their parents, suggests Ed Vere…

- by Ed Vere

The first books I liked, and got properly absorbed in, were Richard Scarry’s. I adored them; the pictures were wonderfully rich, and there were so many narratives and lives you could imagine. It was a beautiful world to enter, for a very young child.

Later, when I was six or seven, I devoured The Wind in the Willows, and as an older reader I was gripped by the exploits of the Famous Five, and addicted to Willard Price’s Adventure series. I hoovered that stuff up.

But what I remember most of all about my childhood literary experiences is my father sharing the nonsense poetry he loved with me. He was a very good, theatrical reader, and read Lear and Belloc with enormous relish and a dangerous sense of fun. He died a couple of years ago, and I can still hear him declaiming the tale of ‘Jim – who ran away from his nurse and was eaten by a lion’.

I was lucky, in that I was raised in a house where books were massively valued, by parents who read themselves and to me. That kind of influence makes a huge difference; which is why what BookTrust does, in terms of getting books into the hands of children who might not otherwise have access to reading materials, is so powerful.

My book Mr Big was chosen as a Booktime title in 2009, and went out to 750,000 four- and five-year-olds. According to research, three out of ten of those kids would never have been read to by their parents – and for 57% of them, Mr Big would represent the first book they’d owned.

I’ve done a lot of work with the charity since then, and honestly, I cannot overstress the significance of what it does. Opening a book gives you access to so many incredible worlds, and it’s a gateway to all kinds of learning.

It’s such a simple act, to read to a child, and not doing it is such a tragedy. It’s not a question of blame – there are many reasons why reading at home doesn’t happen, including parents never having been read to themselves. BookTrust tries to break that cycle.

Increasingly, as I look around, I see how enormously vibrant the children’s books scene is, and it’s a privilege and a joy to be a part of that. But I do feel a real sense of responsibility as an author and illustrator within that rich ecosystem.

I think we should take seriously what we do, because the truth is, the books we experience when we are young can be foundational to our thinking.

I never want to be didactic, absolutely not; at the same time, though, I believe it’s right that I should be trying to present good messages about how to be – not only because stories can stay with children for their whole lives, but also because when I write a picture book, it’s not only for the child.

It’s also for the grown up who will read that book to the child, and who might have a very different world view from me. I do a lot of events, at schools and literary festivals, and the ones I enjoy the most are those where I have the parents along, too.

At least 50% of what I say is directed at them; and it’s interesting, because when you are entertaining someone’s child, talking and drawing with them, and allowing them to enter the world of books, the normal boundaries between two adults are broken down. You are almost a member of the family; and you can say important things in that space.

Not all of my books have an obvious ‘message’ (and frankly, The Getaway is positively amoral!), but the latest, How to be a Lion, is definitely my most explicitly ‘purposeful’ story so far.

We’re living in an age where certain things need saying. I was doing a book tour in the US in September and October 2016, at the height of the Trump/Clinton presidential campaign. Everyone I met was highly embarrassed, and reassured me that Trump would never actually win – but of course, we’d just had the Brexit vote in the UK, and I couldn’t be so confident.

I saw that Trump was actually appealing to people, despite his odious tactics. His belligerent, bullying voice was drowning out all the others, and I found it horrifying. Especially that this voice would eventually filter down to children.

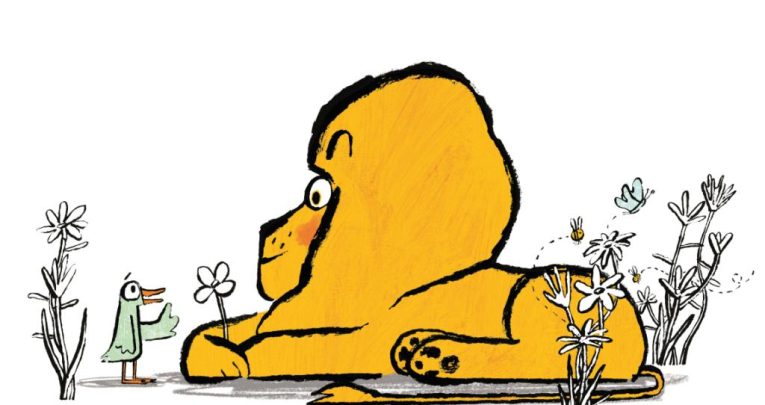

How to be a Lion is my attempt to counter that and demonstrate that you don’t need to act that way in order to be heard; and that gentleness and compassion aren’t weak traits. I want that message to go to everyone, but in this age of ‘toxic’ masculinity, I’d like it to be heard particularly by boys.

There can be a narrow view of masculinity offered to boys. Leonard, my protagonist, is a lion – so he is strong and powerful, but also sensitive and emotionally engaged. He offers an alternative example of how to be a complete and rounded person. He shows the importance of thinking for yourself, and standing up for who you actually are. I hope children and parents alike enjoy getting to know him.

How to be a Lion, by Ed Vere, is published by Puffin (£11.99).