Why Do So Many Children’s Books Kill Off The Parents?

Looking through classic and modern texts for orphans can encourage children to think more deeply about whose story they are reading, explains Huw Powell

- by Huw Powell

Why do so many children’s books feature orphans?” This is a question that I was asked by a group of writers in Bristol. As I stood in front of the microphone, my initial thought was that this was a generalisation, that it was simply not true and that there were plenty of children’s books with strong parental characters. However, the more I considered the question, the more I realised how many novels do feature orphans, or at least the authors have found a way to remove the parents. Think of five classic children’s stories. Where are the parents or guardians? Do they play a significant role? This is certainly not the case in many popular tales, such as Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe.

Thankfully, there are some stories with prominent parental characters, especially picture books and chapter books for younger readers. However, parents feature far less in middle-grade and young adult novels. The Swiss Family Robinson and The Borrowers are rare examples of stories about families working together.

The need for autonomy

In children’s literature, the list of orphaned characters is surprisingly long – ranging from the classic Oliver Twist and David Copperfield to the more modern Alex Rider and Cassie Sullivan. And it’s not just books; this trend is echoed across comics, film and television. In particular, superhero orphans, such as Superman, Spider-Man, Ironman, Captain America, Batman and Robin.

Why do so many authors remove the parents? According to Wikipedia, one definition of an ‘orphan’ is a child bereft through “death or disappearance of, abandonment or desertion by, or separation or loss from, both parents”. Is it their tragic backstory that makes orphaned characters popular, because it encourages sympathy with the reader?

I feared that I had written a cliché with my Spacejackers trilogy. I reminded myself that my main character, Jake Cutler, may not be an orphan, because his father might be alive and waiting for him in the stars. But I had still found a way to remove the parents from the plot, by having Jake abandoned on a remote planet and raised by cyber-monks. Why had I done this? Was it subconsciously related to the death of my own father when I was a child, or perhaps something to do with becoming a father myself?

The answer is far simpler.

A child character cannot act autonomously in the presence of their parents. In literature, parental figures represent rules and order, therefore it’s only when they are removed that the children are free to step up. For a child to be the main character, they need to be thrust into the driving seat, so that they can take control and make their own decisions. But this freedom comes at a price, because a family can also offer comfort and support, meaning that a ‘parentless’ character can find themself unanchored and exposed, which was taken to the extreme in Lord of the Flies. In most stories, the more challenging the situation, the more the reader can share the main character’s elation when they overcome the odds and achieve their goal.

Unconventional heroes

Think how different some books would be if the main characters had not been orphaned. It’s hard to conceive Oliver Twist not meeting Fagin, or Tarzan growing up in a boarding school, or Paddington Bear remaining in darkest Peru. In Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince, Harry reflects about how different his life would have been if his parents had lived. Aboard the Hogwarts Express, he imagines “a scarless Harry who would have been kissed good-bye by his own mother, not Ron’s.” But would this have made such a gripping story for readers? It’s unlikely that Harry would have experienced such dangerous adventures under the protection of his parents.

“Harry’s status as orphan gives him a freedom other children can only dream about,” elaborates JK Rowling in an interview for Salon. “No child wants to lose their parents, yet the idea of being removed from the expectations of parents is alluring. The orphan in literature is freed from the obligation to satisfy his / her parents, and from the inevitable realisation that his / her parents are flawed human beings.”

It’s worth noting that many children do not come from a conventional family unit as portrayed in the books they read. However, we’re starting to see new authors move away from traditional stereotypes and embrace a more diverse definition of family. In the Twilight trilogy, for example, Stephenie Meyer promotes a strong sense of family, but this is explored within different contexts, such as divorced parents, fostered vampires and a werewolf pack.

Whatever the definition, the main character must still be allowed to experience their own adventure and fight their own battles, which is often not possible with their parents in the room. So, while it’s not essential for children’s authors to ‘kill the parents’, the removal of parents or guardians forces a child character to stand on their own feet and become the hero of their own story.

10 iconic literary orphans

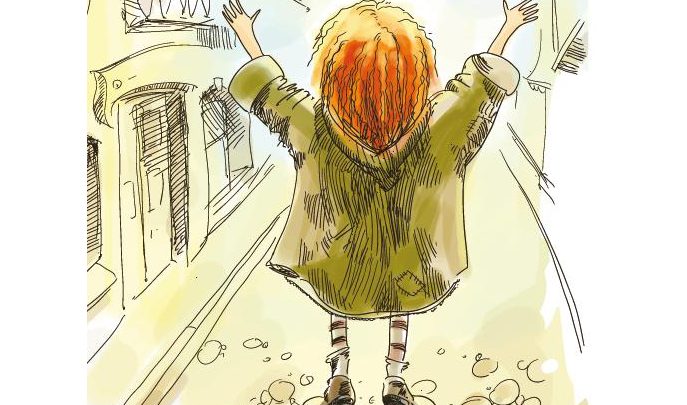

1. Oliver Twist – the unfortunate boy who experiences the cruel streets of London in the 19th century. 2. Peter Pan – the lost boy from Neverland who refuses to grow up. 3. Harry Potter – the tragic trainee wizard who embarks on a magical education. 4. Mowgli – the feral boy raised by wolves in the Indian jungle. 5. Dorothy Gale – the farm girl from Kansas who meets the wonderful Wizard of Oz. 6. James Bond – the charismatic secret agent who works for MI6 as codename 007. 7. Tarzan – the lord of the African jungle who was raised by apes. 8. Anne Shirley – the spirited girl who is mistakenly sent to Green Gables farm. 9. Pollyanna Whittier – the optimistic girl who transforms a dispirited Vermont town. 10. Paddington Bear – the marmalade-munching bear from Peru who moves to London. Can your pupils think of any more?

Huw Powell is the author of the Spacejackers series (Bloomsbury)