Why Children Will Never Fall Out Of Love With Dogger

Nikki Gamble recalls the picture books we just can’t leave behind – and suggests new ways to share them in your classroom…

- by Nikki Gamble

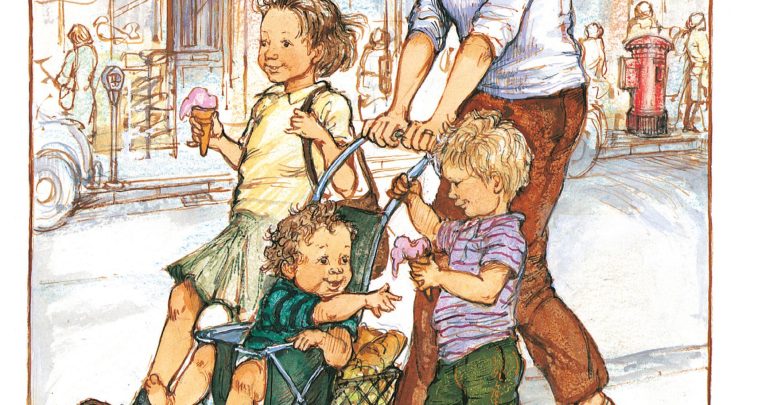

Ask a room full of teachers which books had the most impact on them when they were young children and you can guarantee that both Dogger (Shirley Hughes) and Each Peach Pear Plum (Allan and Janet Ahlberg) will be cited at least once.

Earlier this year, Shirley Hughes was awarded Book Trust’s Lifetime Achievement Award, with Diane Gerald, Book Trust’s CEO commenting that “Shirley’s characters are imprinted on the memories of two or three generations, a recognition of their enduring charm.” More recently, Allan Ahlberg was honoured by his peers including Brian Wildsmith, Shirley Hughes, Quentin Blake, Chris Riddell and Raymond Briggs for his outstanding contribution to children’s books over the course of a career which has inspired children, parents and teachers, as well as a new generation of authors and illustrators.

Dogger and Each Peach Pear Plum were published within a year of each other, and both were awarded the prestigious Greenaway medal. When the Library Association conducted a poll in 2007 to discover which books in the history of the medal were the public’s favourites, those two unforgettable books were awarded first and second places, with just 1% of the vote separating the pair. Why is it that these stories, along with a handful of other, iconic picture books, continue to delight young – and importantly, not so young – readers, decades after they were first published? What is their enduring appeal?

Heart to heart

From an initial glance it isn’t easy to see what the connections might be: Dogger is a straightforward, realistic family story about the loss of a favourite toy, while Each Peach Pear Plum is a playful fantasy populated with familiar nursery story characters. However, what does connect them – and the other books mentioned in this article – is an indefinable quality that might be called ‘soul’. There are many accomplished, clever and beautiful books, but the classic is marked out by having a deeper layer which comes from emotional authenticity, thrown into focus and consummately rendered through words and illustrations. Dogger is so powerful because it taps into universal feelings of loss in an accessible way so that it can be understood by a young child just as powerfully as a grown-up. Children and adults respond to these classic books at the ‘feeling’ rather than ‘thinking’ level, in the same way that a particularly soulful piece of music might raise a tear or a smile. Didacticism and moralising have no place – these stories do not seek to teach or lecture, though many lessons will be learnt from reading them.

It is part of their essence that classic picture books appeal simultaneously to adults and children. They are, as Victor Watson describes them, ‘love stories’ concerned with the love between an adult and a child. This operates at a profound level, much deeper than the plot.

So for example, The Very Hungry Caterpillar and Where the Wild Things Are can be seen as aspirational stories; they deal, albeit metaphorically, with growing up and inevitably leaving childhood behind. At the same time the authors ascribe a state of grace to childhood, which the adult sharing the book recognises and responds to as something precious that cannot be recovered, only relived through memories. Some books achieve this sensibility through playfulness and invention; Each Peach Pear Plum, with its memorable rhyming text based on a traditional nursery rhyme, is deliberately nostalgic. The Ahlbergs present a technology-free nursery world, where familiar characters are spotted as the pages are turned. It is this ‘drama of the turning page’ (Ahlberg) that makes Rosie’s Walk such a thrilling experience for a young child (many EYFS teachers will be familiar with the excited gasps of anticipation that this story generates). Similarly in We’re Going on a Bear Hunt, adults and children are implicitly invited to enact the story together and Helen Oxenbury’s masterly illustration, which shows Dad fully participating in his children’s playful adventures, reinforces the adult/child shared experience.

The qualities of the classic picture book allow for many re-readings. Dealing with themes of love, loss, redemption, acceptance, carnival, growing-up and so on, they reflect what is best in humanity – and as already suggested, the books will resonate with readers in different ways each time they are revisited. Although many children will have experienced these stories before they start school, they should be visible in classrooms and school libraries, and used for whole class shared reading so that children develop and deepen their responses.

Classic ideas

Here are a few suggestions of ways you and your pupils can breathe new life into some favourite picture books:

Where the Wild Things Are (1963)

Max visits the place of the Wild Things in his imagination. Have the children create their own imaginary landscapes using a range of art materials. Encourage work on large scale by having big rolls of paper as well as individual sheets available.

Mr Gumpy’s Outing (1970)

Create a drama based on Mr Gumpy’s outing. Assign animal roles to each of the children – you could make animal masks beforehand. Then improvise the trip down the river; as the boat sinks lower into the water, how do the animals react? When the boat finally tips, everyone swims to the shore and shakes and squeezes the water from their fur and clothes before settling down for a lovely afternoon tea.

Dogger (1977)

Invite the children to bring favourite toys into school (you may want to stipulate ‘soft toys’ to avoid games consoles, etc.). Bring one of your own and tell the children all about it. Have pupils draw their toys and write a few words about why theirs is so special. Sit in a circle and share the children’s words and pictures. Together, summarise some of the reasons why toys might be important to us.

Rosie’s Walk (1968)

We never find out what Rosie and the fox are thinking, or what they might say. Give the children some blank speech and thought bubbles and have them write down their ideas. Share the different versions and invite the children to explain their choices.

Gorilla (1983)

This third person story is told from Hannah’s point of view. How would it be different if it were told from the Gorilla’s (or Dad’s) perspective? Who is the Gorilla? Where did he come from? Why does he visit Hannah? What does he do after his visit to Hannah?

The Snowman (1978)

The Snowman is completely wordless, but you can tell the story. Allocate different parts of the narrative to pairs of children. Ask them to work on voicing their ‘chapter’ in an exciting and expressive way. Bring everyone together in a storytelling circle and invite the children to retell the whole story in their own words. You may want to record their version to accompany the book in the school or class library.