Axel Scheffler – Use the art of illustration to help pupils with character development

Could the art of illustration help your pupils with character development in their writing? TR&W spoke to Axel Scheffler, in search of the inside story…

- by Axel Scheffler

- Illustrator best known for his work with author Julia Donaldson Visit website

TR&W How early in the story development do you get involved, as the illustrator?

AS Not until it’s absolutely finished. For example, when I’m working with Julia [Donaldson], she sends the text to the publisher to be edited. Then the editor, Alison Green, sends me the final text, plus some notes. And then it’s over to me. I don’t have any say in the plot – quite rightly so! It’s always been that way, and it works very well. Sometimes there might be little notes from Julia, saying what she imagines, but that’s very rare, actually. Alison and her art director, Zoë Tucker, work out how the text should be divided up into separate pages, and they give me some suggestions on the page design to get me started. Then I begin developing the characters. I start sketching first, then there are conversations with Alison and Zoë about which way it might eventually go.

So, does the final appearance of a character often differ greatly from your original version?

Yes, sometimes! With the Gruffalo, I started sketching without thinking very much (as usual!), and I made him really quite scary, with tiny eyes and huge claws and fangs. Alison suggested that I should probably tone him down a bit, which is why he ended up being a rather more lovable monster than the one I first imagined. The old lady in A Squash and a Squeeze went through some alterations, too. I started out by making her very elderly indeed, and quite spiky, with a pointed nose and so on. After some nudges by the editor she became rounder, kinder and less wrinkly. So there are compromises; but publishers do tend to know what they are talking about (most of the time, at least), and I tend to listen to what they say. I still draw what’s in my mind, but I know there are some broad rules you need to follow, and a few taboos to avoid.

Over the years you’ve been asked to develop characters who are human beings, farm and wild animals and sea creatures… not to mention giants, witches and other fantastical beings. Do you find it easier to start with someone or something that already exists in the world, or from scratch?

I suppose it’s more fun to create a character from scratch – but of course, even when you are coming up with images of fantastic beasts and magical figures, there is often a whole range of culturally transmitted images that you need to take into consideration. For example, British readers would expect a witch to wear a pointy hat, but in Germany, she would more likely be in a headscarf.

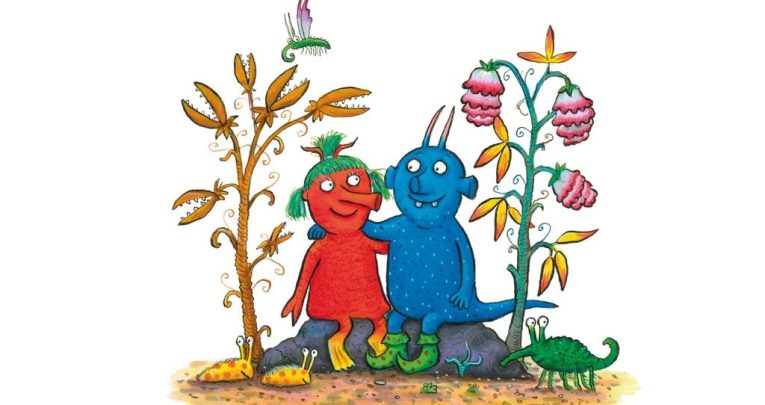

In your latest collaboration with Julia Donaldson, The Smeds and the Smoos, there are very few textual clues as to the characters’ appearances – so how did that process work?

That’s right, there were only a couple of attributes in the text for each type of alien: wild hair and sleeping in beds for the Smeds; wearing shoes and jumping like kangaroos for the Smoos. So I had a few constraints – I would normally draw aliens with eyes on stalks, which didn’t work when they needed to have hair – but other than that I had free rein. I did lots of sketches before deciding on a direction, and it was nice to have such freedom.

Do you think, if you’d chosen different sketches to take forwards, it would have changed the story, even if the words stayed the same?

Different illustrations can absolutely result in different stories. Every time I’m approaching a new concept, I can see endless possibilities. When I do talks at schools I always show my original Gruffalo sketches, and talk about how I have to make decisions as an illustrator. From a very brief description, you can come up with a whole range of appearances for a character, and each one might highlight different qualities.

What advice do you have for primary school teachers who would like to make more use of drawing in their literacy teaching?

Just as reading lots of books can help with writing, being exposed to all kinds of different illustrations can inspire children to draw – and give them an understanding of drawing. It’s a good idea to get children to look at work by different illustrators and talk about what they do. You could discuss the various techniques and media they use – collage, watercolours, pencils – and encourage children to try them for themselves. It’s important to think about how the illustrations work with the story – what are the overlaps between the text and the pictures? Is there anything that’s in one and not in the other, or vice versa? And don’t forget to introduce them to fine art – because really, that’s illustration, too!

Try it in your classroom

Four Axel-inspired ideas to help children make links between illustration and writing

- Read out a very short description of a character to your class, then ask them to draw the person or creature you have been describing. Collect in all the pictures, then hand them back out again, randomly. What differences do the children notice between their own work, and the illustration they are now looking at? Has everyone been true to the original description? What additional information has been added, and how?