The Sixth Sense – Proprioception, And Why Your Early Learners Need To Develop It

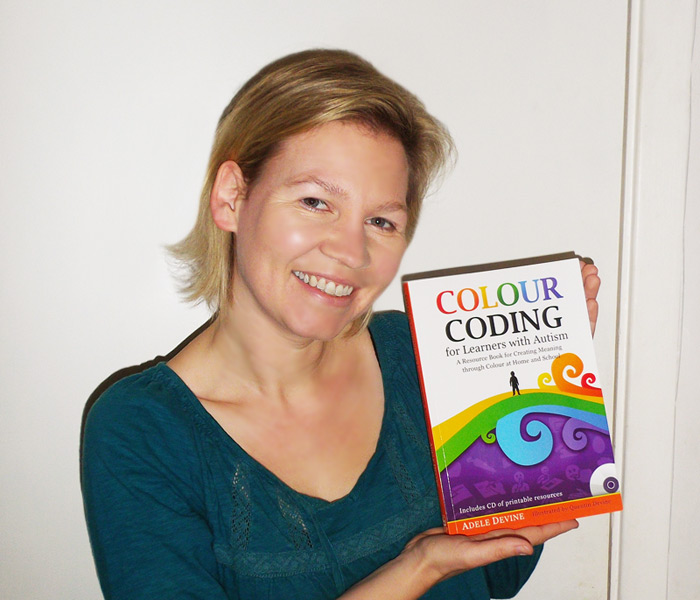

That bouncy child may still be learning where his own body is in space, says Adele Devine…

- by Adele Devine

- Early years and SEN specialist, author, keynote speaker and trainer Visit website

Close your eyes and raise your arms above your head. Can you get your thumbs to touch? Imagine if you couldn’t even get your hands to meet?

What if, through lacking this ability, you misjudged your movements when lifting your cup of tea and soaked your shirt? Or collided with other members of staff as you walked down the corridor?

We all know the five senses – sight, sound, smell, taste and touch – but there is a sixth sense we sometimes forget about entirely; one that our bodies and brains use to gain vital information about the world. This sense is position and movement (knowing where our body is in space), also known as the ‘sense of proprioception’. Imagine how topsy-turvy and confusing the world could seem without this sense to call upon… Babies begin to develop the sense of proprioception from birth, using their hands to reach, to clutch and then explore things with their mouths. This is also the reason that infants often sleep better when securely swaddled. We help develop this sense with activities like baby massage or ‘tummy time’, and by encouraging young children to reach out and experience motion through bouncing, swinging, sliding and turning. But what if that connection in the brain does not develop? If a child seems to lack the sense of proprioception, we must investigate, build trust and support their differing needs.

Issues to be aware of

Carl W. Buehner once observed, “They may forget what you said – but they will never forget how you made them feel.” Be aware of that sixth sense. Note how your children navigate space, perform gross and fine motor tasks, and how they speak. You should seek the advice of an occupational therapist or speech therapist if you have concerns.

In your own setting, ensure that you have sensory integration equipment available, and consider creating a ‘sensory diet’, as described in the case study below, to support individual needs if required.

Case study – ‘Ali’s new Squease’

On the go! Ali was a little whirlwind, running, climbing and leaping about; he needed one-to-one support at all times. The only times Ali was still was when he was in a buggy. He actually didn’t need a buggy, as he was physically very able – but if there was one in class, he would rush to get into it and seem comforted by the support. This wasn’t ideal, but if this was a sensory need, we wanted to try to find a way to support it.

Individual support We tried using a swing, which Ali liked, but it didn’t have the buggy effect. We searched for a type of seat that would offer the same feedback as a buggy, but Ali wanted to be on the move and have the buggy feeling. Over time, we found that Ali liked to be pushed around in our little car. He started to come and take our hands to get us to push him. I gave him a large ‘help’ symbol with a hand on it, which he learnt to exchange with staff to get them to push the buggy – a great step forwards with developing communication through PECS.

Outcomes We knew Ali would eventually outgrow the car, so we decided to trial a pressure vest. The first time I put the ‘Squease’ vest on Ali, he was calmer. He sat on my knee for 15 minutes, then sat on the floor amidst the group of children and stayed for five minutes. We had never seen him do this before. He seemed less anxious, more able to focus on where he was and less bombarded by his surroundings. Could deep pressure do this?

We continued our trial and the positive impact continued. Mum mentioned that Ali was calmer at home too. Recognising and helping to meet Ali’s sensory needs made such a difference.

Case study ‘Sol’s soft-play’

A sensory diet On our first home visit Sol zoomed into the room – and stopped just short of banging his head on a TV unit. It had once caused a visit to hospital, Mum told us, and he knew that it could hurt him.

In class, he explored by climbing on furniture and jumping off radiators. We created an individual sensory diet filled with activities to meet his needs – he had trampoline time, swimming, soft-play, outside play and access to our sensory circuits.

Unexpected resistance Each week we visited a local soft-play centre. We expected it to be perfect for Sol, but when we arrived he seemed genuinely terrified and refused to leave his buggy. We realised we needed to take smaller steps, and started by taking the buggy into the soft-play.

Sol loved the trampoline in our classroom, so we moved the buggy near the soft-play trampoline. Eventually we coaxed him into having a go. These bounces started out short, but became longer each visit.

Real improvement In time, Sol became braver. He still needed to process the surroundings after arrival, but was now was less anxious and more curious. We never forced him, but always encouraged him. It took months and months of soft-play outings, but by the end of the year, Sol was climbing all the way to the top of the big slides and then sliding down (sat on a member of staff) with the biggest, brightest smile on his face.

Get equipped

10 resources that can help develop children’s sense of proprioception…

• Balance beams • Steps • Trampolines • Large therapy balls • Weighted balls • Weighted blankets • Swings and slides • Different floor textures • Soft-play • Dark dens

Adele Devine is a teacher at Portesbery School & director of SEN Assist; for more information, visit www.senassist.com or follow @AdeleDevine