The problem of perfectionism – What happens when students chase unrealistic expectations

Rob Lightfoot explains how a ‘perfectionism literacy’ intervention can benefit everyone…

Do you have a student who struggles to call a piece of work ‘finished’? Who would rather hand in nothing at all than something they’re not 100% happy with?

I’m sure every secondary teacher knows many students like this. Some may have even once been that student themselves. Most of us can relate to these traits in at least one sphere of our lives, whether it’s the feeling that we’re letting our team down when we don’t perform to our perceived best, or the sleepless nights when we consider ourselves to have fallen off the Parent-of-the-Year pedestal we’ve set our sights on.

Yet while most of us will have admit to being ‘a bit of a perfectionist’ at some point, perfectionistic traits are in fact widely misunderstood – and an area of growing concern for our young people.

Over the past few years, the National Association for Able Children in Education has partnered with a team of researchers headed by Professor Andrew P. Hill at York St John University, focusing on perfectionistic characteristics in highly able learners. This has developed our understanding of the potentially harmful impact of high levels of perfectionistic characteristics, their increasing prevalence, and the capacity of schools to make effective interventions.

What’s the impact?

When students are perfectionistic, they place unrealistic expectations on themselves and others, or report experiencing pressure from others to be perfect (Hewitt & Flett, 1991). These expectations might pertain to academic achievement, appearance, sporting achievements, or indeed any area of life they consider important.

Being perfectionistic is common among students, and research suggests that it’s increasing, with young people more perfectionistic than ever before (Curran & Hill, 2019). The onset of the pandemic will certainly have done nothing to lessen these increasing levels of perfectionistic characteristics in our adolescents.

The consequences of perfectionism on performance are complex. On one hand, there’s evidence to show that students who are perfectionistic can outperform their peers academically. On the other hand, there’s also evidence demonstrating that students who are perfectionistic may find setbacks particularly difficult to deal with, causing their motivation and performance to suffer in the longer term.

The consequences of perfectionism for mental health and wellbeing are much clearer. Students who are perfectionistic are generally likely to be more worried and anxious, and more vulnerable to a range of mental health and wellbeing difficulties.

‘Perfectionism literacy’

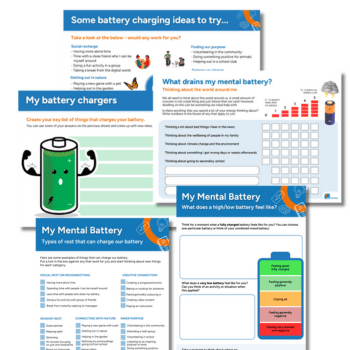

One way of supporting these students is to increase their ‘perfectionism literacy’ – that is, the ability to recognise the features and origins of perfectionism, and the differences between perfectionism and trying one’s best. Tied in with this is giving students knowledge of the help available, and encouraging their willingness to seek it out.

Our aforementioned collaboration with York St John University sought to evaluate the effectiveness of a single classroom-based lesson specifically designed to teach these skills. Following the lesson, the students reported having more knowledge of perfectionism and could recognise the importance of seeking support if needed.

The lesson was found to provide an easily implemented, preventive intervention for schools to help reduce the negative effects of perfectionism, from which we would made the following recommendations:

- A perfectionism literacy lesson can be a valuable addition to activities based around safeguarding, mental health and wellbeing.

- Teachers should consider the degree to which current classroom practice might be inadvertently encouraging perfectionistic thinking in their students. Unrealistic expectations, frequent or excessive criticism, anxiousness over mistakes, and public use of rewards and sanctions can all reinforce perfectionism.

- Schools ought to ensure that teachers can recognise the development of difficulties associated with perfectionism. Increasing perfectionism literacy among teachers may therefore be a useful way of supporting student wellbeing.

The resources developed for the perfectionism literacy intervention are freely available to all schools, along with guidance on how to use them and lesson materials for staff and students. For more details, visit nace.co.uk/perfectionism.

Rob Lightfoot is CEO of NACE; for more information, visit nace.co.uk or follow @naceuk