SEND primary school – sensory strategies for the classroom

Whether it’s listening to music, running a lap, or taking a deep breath, we all have ways to calm down and focus. Dr Ivana Lessner Listiakova explains how this can work in schools…

Do you have a child like this in your class?

- Appears to be slow, unmotivated or daydreaming

- Keeps running around, jumping up from their chair, or rocking

- Gets angry at other children out of the blue

- Chews their pencils and bites their nails

- Avoids active participation

Yes? Then this article is for you.

Aside from being problematic to an organised and peaceful classroom, challenging behaviour, difficulties paying attention and problems with emotional regulation may be caused by unmet sensory processing needs, which can result in undue stress on both pupil and teacher, and can get in the way of meaningful learning.

We have seven sensory systems: visual – sight; auditory – hearing; olfactory – smell; gustatory – taste; tactile – touch; proprioception – body awareness; and vestibular – balance. They all play a part in effective learning.

To be able to learn and coordinate our movements, we need our nervous system to process all the information coming through these systems, as well as from our environment. We can then make sense of the information, and use it purposefully in meaningful activities.

For example, writing your name. In order for a child to develop this skill, firstly they need to be sitting still. They need to be able to hold the pencil, apply the right pressure and have muscle control over the shapes.

Only then can they form the letters on paper. At the same time, the child needs to filter out any excess information that is not crucial to the moment. For example, the sounds of chairs on the floor, voices of other children, seeing other objects on the table and on the walls, and feeling their clothes touching their body.

Designing sensory strategies

Managing pupils’ sensory processing needs can go a long way to helping them settle into learning, and sensory strategies are an effective way of doing so.

These are adjustments we can put in place in the classroom to modify a child’s environment or required tasks. However, it’s not always as straightforward as it sounds.

To design effective sensory strategies for the school environment, we need a good assessment of the sensory needs of individual children, and a good understanding of how sensory processing works in general. These starting points enable us to tailor strategies which identify individual needs.

So, when is it a good idea to consider offering a sensory strategy?

Hypersensitivity and hyposensitivity

There are two ends to the range of sensory sensitivity – hypersensitive and hyposensitive. In other words, children who run, jump around and cannot sit still, and children who daydream and are happy in their slower world.

Hypersensitive children let too much information into their sensory processing system and can become easily overwhelmed.

This can result in fight, flight or freeze responses, and pupils are likely to protect themselves against experiences they perceive as threatening or stressful.

This can lead to heightened anxiety, irritable reactions for ‘no apparent reason’ and difficulties in emotional regulation. The response can also become externalised in challenging behaviour such as hitting other children, screaming etc.

When the reaction of the child is not to fight, but rather to escape the situation, they might refuse to do something, which again can be considered challenging behaviour, although it is a natural protective reaction. If children do not have the opportunity to avoid overwhelming stimuli, they can sometimes find themselves in meltdowns or complete shutdowns.

Higher sensitivity (and reactivity) is typical for pupils on the autism spectrum. It is mainly auditory, visual and tactile hypersensitivity (defensiveness), but sensitivity to touch is also typical for children who appear hyperactive – they are often over vigilant because they want to avoid accidental touch.

In contrast, hyposensitive children may need additional input to feed their brain with information that can be processed and used effectively in everyday tasks.

In these cases, it is common to see difficulties in fine and gross motor skills, organisation, planning, and attention, which can sometimes lead to frustration.

To put it another way, it might seem as if a wall exists between the child and the world, and that we need to manually input sensory information to reach them.

This is where the sensory strategies come in. We can use these strategies to provide opportunities for the pupil to experience sensations that are crucial for the development of skills many of us take for granted, such as sitting, writing, drawing, cutting with scissors, using kitchen utensils, getting dressed, playing football etc.

But to do all of this with confidence and without hurting ourselves, we need our sensory systems to be working in unison.

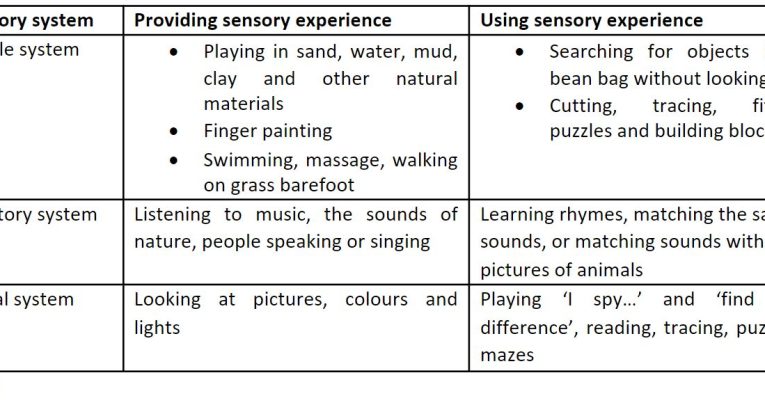

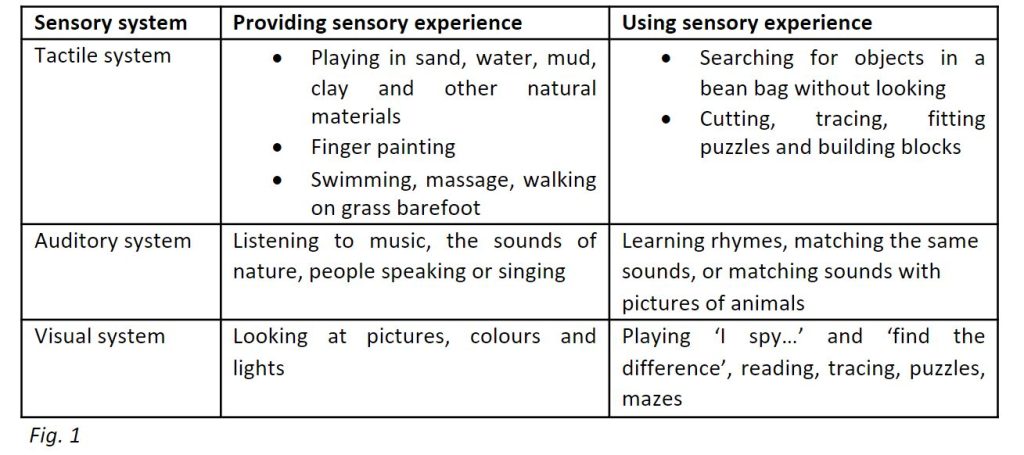

Through providing sensory experience we can design activities that use sensory discrimination. For example:

What can we do in the classroom?

One of the most obvious issues in the classroom is when a child simply isn’t paying attention. However, this could be for a number of reasons.

Our attention, or activity (arousal) level is naturally regulated by vestibular inputs. So, for instance when we want to calm down and fall asleep, slow regular rocking can help.

On the other hand, when we need to wake up, we engage in activities that include movement (especially movement of the head).

Both hyperactive and hypoactive pupils can benefit from the same vestibular strategies. Either way, all children in the classroom can sometimes use a boost and regulation of their attention.

For ‘fidgety’ pupils, we can provide movement breaks or incorporate movement into the curriculum (e.g. squats while doing maths or spelling), encourage active movement during breaks, and not punish children for moving around the classroom.

If you are worried about children becoming agitated, always involve activities that include a lot of proprioception. This regulates the brain, organises and calms, while allowing them to maintain optimal levels of activity.

Proprioceptive activities include muscle work such as climbing, hanging, pushing the walls, or pushing yourself up from a chair; carrying heavy beanbags, backpacks or floor mats; building forts from heavy materials; squats, push ups or wheelbarrows.

In cases of high sensitivity, you could try:

- Removing sensory inputs that bother the child

- Providing the pupil with a sense of control over the situation – eg letting them sit near a wall where they are protected from the back and can see the rest of the room

- Creating opportunities for proprioceptive input

- Giving tools to the child that they can use independently that a) help eliminate the bothering sensation (eg ear defenders, sunglasses, long sleeves/short sleeves), and b) add more proprioception when the child starts getting anxious (eg chewing necklace or pencil top).

Remember, these strategies target sensory processing through fun, purposeful activities that are meaningful to the child because they are part of everyday life, play and learning. I hope they help you support your pupils and their learning.

Dr Ivana Lessner Listiakova is a senior lecturer in childhood studies at the School of Social Sciences and Humanities, University of Suffolk.