How do we Ensure Every Student Really Has Understood?

Students are rarely the best judges of what they actually understand, which is why we need clear strategies to find out what they really know, insists Emma McCrae…

- by Emma McCrea

One in three things a student will have learnt by the end of a lesson will not be known by any other student.

Graham Nuthall uncovered this incredible finding in his lifelong exploration to discover what really goes on in classrooms.

To compound this, he discovered that the remaining two things a pupil learns are learnt by no more than three or four of their peers – despite our carefully planned and well-intended learning objectives.

Given these astonishing findings, it is vital for us to find out what our students know – and more importantly, what they don’t know.

How we do this is difficult. Students can suffer from a cognitive bias called the Dunning–Kruger effect which describes how novices (those with less knowledge and experience) can lack the understanding required to be able to correctly assess whether they understand or not.

This means that some of our young people may think they understand, when really, they don’t.

Faced with questions such as ‘Everybody got it?’, ‘Do you understand?’ and ‘Are we all happy with this before we move on?’, students suffering from the Dunning-Kruger effect are likely to nod along, providing us with inaccurate feedback.

Problem solving

If we want more reliable information, a general rule of thumb is to avoid questions like these that have yes/no answers, along with other, supposedly more effective methods for checking understanding – including self-assessment strategies such as thumbs up/down, 1–5 rating using the fingers, and traffic lights (red, amber, green or RAG).

While these techniques do provide us with information, we need to be very careful when making judgements about student understanding which have arisen from self-assessment questions.

That isn’t to say there is no place for such questions, just that we need to be mindful of the Dunning–Kruger effect and the subjective nature of the responses.

These methods are actually assessing student confidence, not competence, but too often they are used as a measure of the latter.

Instead, to gather information we can rely on, we need to pose problems to our students.

For example, if in maths we have shown learners how to expand brackets, such as 2(x + 5), we could give them a similar problem to solve, such as 2(x+ 6) or 3(x+ 5) or 2(y + 5).

This approach is preferable because it leaves no space for the Dunning–Kruger effect or subjective responses – the students can either solve the problem or not. The most effective way to do this is by using mini whiteboards so that all responses can be checked.

In my humble opinion, mini whiteboards are the single most powerful resource we have to hand. They allow us to make knowledge and, more importantly, lack of knowledge visible.

Assuming we ask the right questions, they allow us to easily assess if students understand or not. That said, for them to be effective, we must ensure we build good routines for their use and respond appropriately to the information gained.

Prompt questions

Another powerful strategy for unpicking what students know and don’t know is student self-explanation.

Imagine you are on a professional development course. The trainer is talking and you are taking notes which list the main ideas in a way that helps you to understand (rather than writing word for word what the trainer is saying).

You are listening to the trainer, analysing the content and summarising the ideas.

Notice that you are not explaining to a colleague sitting next to you or answering a question the trainer has asked.

You are self-explaining, the goal of which is to make sense of what you are reading or hearing – an important part of the learning process.

Unfortunately, students do not tend to self-explain on their own.

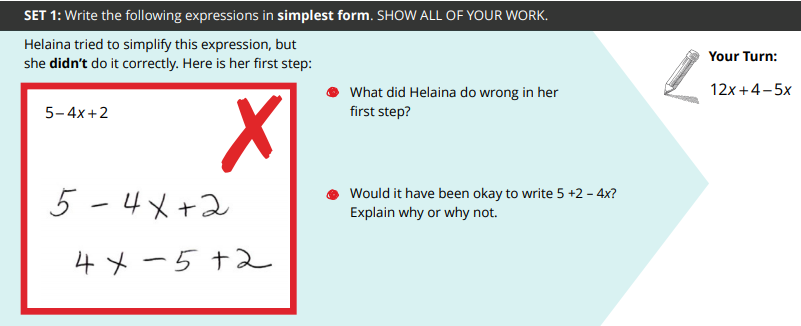

Thus, we need to provide scaffolding. Asking students to annotate a worked example (a problem that has already been solved for the student, with every step clearly shown) or their solution to a problem is one way, while another is to provide prompts when they are faced with worked examples.

© SERP Institute

For example, you could share the incorrect worked example above with the students, whereby the prompts used to encourage students to self-explain are:- What did Helaina do wrong in her first step?

- Would it have been okay to write 5 + 2 – 4x? Explain why or why not.

The first prompt focuses on identifying the error – what did Helaina do wrong?

Pair these types of prompts (often beginning with what: what is wrong? What mistake was made? What is the correct solution?) with those that encourage the students to elaborate and explain their reasoning – explain why or why not is used here.

Prompts beginning with why help students to do this: why did Helaina rewrite the expression in this way?

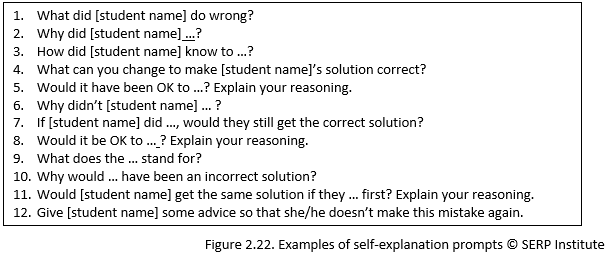

The panel below lists some example self-explanation prompts including my favourite, ‘Give Helaina some advice so that she doesn’t make this mistake again.’

These kinds of prompts can be used with every type of worked example, including correct and incomplete worked examples.

It is best to get the students to write down their responses – the key to this strategy is to self-explain, not explain to a peer or teacher.

For inspiration and freely downloadable resources check out the excellent AlgebraByExample and MathByExample materials which harness the combined power of worked examples and student self-explanation.

Exit tickets

Lastly, we can use exit tickets at the end of our lessons to take stock of what students know and don’t know.

This helps to inform subsequent lesson planning. To create their content, identify a couple of problems relating to the learning objective that we want the students to be able to solve, or use worked examples with self-explanation prompts.

The students solve these problems on a piece of paper and hand them in on their way out of the lesson. Be flexible – lessons don’t always go to plan and you may need to change the problems you had planned to use.

Exit tickets don’t needing marking in the traditional sense. Examine each ticket and place them into piles – for example, two (correct and incorrect) or three (incorrect, some correct, all correct).

The size of the piles can then inform your next steps, which will vary from speaking to an individual student, creating a relevant starter to highlight an issue or reteaching part of the lesson.

Finding out what students really know is crucial. Asking better questions, encouraging students to self-explain and using exit tickets are three strategies that can help unpick this in the hope we can make every lesson count.

Emma McCrea is author of Making Every Maths Lesson Count (Crown House), and a teacher educator. She tweets @MccreaEmma.

Excerpts from AlgebraByExample used with permission of SERP. © Strategic Education Research Partnership serpinstitute.org