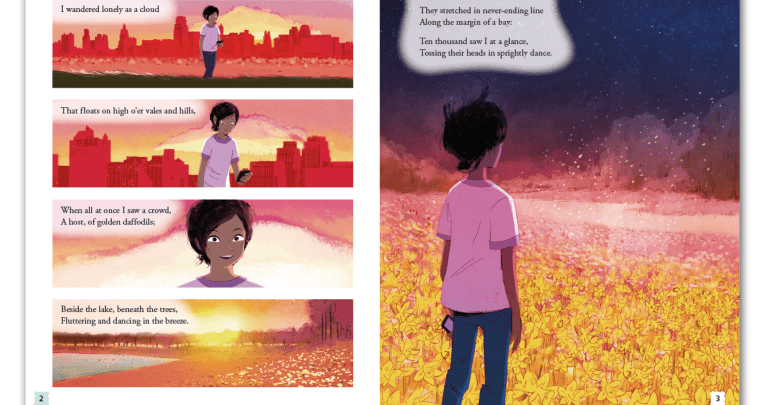

How comics boost reading comprehension

If children are word-reading but not understanding, graphic texts will help make them masters of meaning and inference…

- by Lindsay Pickton and Christine Chen

- Authors, resource creators and co-founders of Primary Education Advisors Visit website

Comics haven’t always enjoyed the same literary status as traditional texts. Even now, they’re frequently seen as little more than a means to get reluctant children (usually boys) reading.

This, to our minds, doesn’t acknowledge the true worth of a form that can literally transform the imaginative lives of young readers, irrespective of their gender.

While it’s true that graphic texts, with their low word count, are unlikely to contribute significantly to a child’s reading speed or stamina, they can have a dramatic impact on reading comprehension (and even written composition) at all levels and so form part of the broader reading diet of all primary age children.

1 | Get back to comprehension

Increasingly, we encounter children whose strong, phonics-pumped word-reading abilities are paired with comprehension skills that are, frankly, lacking.

A great antidote is for children to read a graphic text and then join together to discuss it. This book group-like approach is generally one of the more effective ways of running guided reading, but is essential with comics.

The reason graphic texts work so well for children who struggle with comprehension and word reading is that, although the word count is relatively low, there’s still so much to talk about.

2 | Analyse the artwork

Working with the author, a graphic artist will make similar decisions to a film director when it comes to how each frame will make an impact on the viewer. Thinking about this in the classroom leads to a more advanced level of analysis.

Make sure children notice when there is a close-up – a face, a hand, some inanimate object. What’s the effect of this? Similarly, draw attention to the viewpoint: is a panel drawn as if viewed from above, from below, or perhaps seen through the eyes of a character? Why have these choices been made and why?

As well as the interpretation of what we might call camera angle choices, consider lighting and props. Where is the light coming from and where do the shadows fall? Why has the illustrator placed those documents on that table?

Children’s understanding of the use of viewpoint and the ways in which atmosphere is created in comics can then be extended to more traditional texts. It can even help them to achieve similar results in their own narratives.

3 | Give new vocab context

The way in which illustrations can scaffold the meaning of unknown words is a significant factor in how we (a girl with EAL and a reluctant / remedial boy) became avid and advanced readers. But as we mentioned earlier, these benefits ought to extend beyond those children working at a current deficit. With the right high-quality (but age-appropriate) graphic texts, we can expand the vocabulary of even the most voracious reader.

One option is to look at the growing genre of classics stories retold as graphic texts – Shakespeare, Dickens and Carroll, amongst many others, have received this treatment. To be clear, we are not for one minute suggesting that graphic versions replace the originals (though they may help some children towards them), but a child who is not yet ready to tackle the full Oliver Twist could encounter and grasp challenging vocabulary (and concepts, of course) in the graphic retelling.

Remember also that real reading is not close scrutiny of every word, but rather the understanding of complete pages. The graphic format very much emphasises this – each word contributes to the overall story, and one or two tricky ones here and there can be understood in the context of the whole.

4 | Investigate the spaces between

Dave Gibbons, co-creator of the award winning Watchmen comic / graphic nole, at the passing of time. Does vel, speaks of the need to understand “the white spaces” between the illustrated panels. What isn’t shown?

Investigating this will help build children’s capacity for inference because we are talking about what is implied, rather than known. Look, for exampone panel follow instantaneously from another, or have minutes / hours / days passed?

What must / might have happened in the meantime? Could it be a flashback? Shifts in place should also be noted, or instances when the location is the same, but the viewpoint has flipped.

Once children have reached this level of understanding, draw links between the graphic artist’s manipulation of time and place and the paragraphing of a traditional writer. From here you can ask pupils to think about cohesion and paragraphing in their own writing. Not everything has to be spelled out for the reader and leaping forward in time is often a very effective narrative device.

5 | Become inference experts

Inference is so often the major stumbling block for a young reader, yet the great majority of children are experts at making inferences in their daily lives. They learn to read facial expressions accurately from a very early age and quickly come to conclusions when they look around an unfamiliar room.

Graphic texts require these skills to be exercised on every page, every panel, and most children just get on with it, unaware that they are inferring at all. Capitalise on this by asking them how they know a character is feeling a certain way. How do they know when something bad is about to happen, or what happened the moment before, even though it isn’t drawn or described?

Then, when returning to traditional texts, show them how the same skills apply – though they must see the people and places in their heads by reading and understanding the sentences.

Graphic text resources

If you want to try the ideas in this article, 28 new Project X Origins Graphic Texts for Years 4-6 are available to help children develop higher-level comprehension. Created by 2016 Comics Laureate Dave Gibbons, and comprehension experts Lindsay Pickton and Christine Chen, they introduce sophisticated vocabulary and generate meaningful discussion that develops inference.

Christine Chen and Lindsay Pickton are independent Primary Education Advisors supporting English development nationally. They both grew up as avid readers of comics!