GCSE revision – Maximising potential from KS3 onwards

Preparing for exams can be a daunting task, so here’s how to help students cultivate effective study habits…

- by Teachwire

- Classroom expertise and free resources for teachers

As exam day draws nearer, we look at how to help students utilise their remaining time wisely. We also explore the importance of starting GCSE revision early by laying a foundation of strong habits during Key Stage 3…

What should students’ preparation priorities be?

Counting down the weeks to exam day? Meera Chudasama looks at how to help students make the most of the time they have left…

As students embark on the final leg of their GCSE journey, our teaching practices will naturally change to support a different rhythm of learning.

Students will increasingly focus on identifying gaps in their existing knowledge. This means that as teachers, we must pay careful attention to what their individual learning needs now are.

Here, I’ll seek to share some effective practice that can facilitate students’ revision. This includes exercising memory recall and finding ways of making exam practice less repetitive. It also includes ensuring that students are clear as to what they need to do in order to attain their final goals.

Removing the scaffolds

One key change in our teaching practice during revision season is the removal of embedded scaffolds. Taking away those firmly established scaffolds and removing some of the chunking we do in the classroom will enable students to grow and become more independent learners.

This is an important step in their learning journey. It confirms their transition from looking to the teacher to deliver content, to instead relying more on themselves for what Luis C. Moll et al. refer to as ‘Funds of knowledge’.

Here, I will share some revision activities ordered by what each sets out to do, and what the students want to achieve.

Gaps in knowledge

I like to start with a SWOT analysis. Get students identifying their strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and any threats to them achieving their GCSE goals.

These don’t necessarily have to be subject-specific. Support with student-friendly mark schemes and course outlines. Students should come up with a range of points. This might be a focus on what exam questions will likely come up. Or it might be specific skill areas that may need addressing or methods for further improving those skills.

Another way of getting students to identify gaps in their knowledge can be through checklists, or ‘pit stops’ via the schemes of revision you’re delivering.

Memory recall

Embedding effective retrieval practices will help students transfer relevant content from their long-term memory to their working memory.

Useful strategies here can include quizzing, getting students to re-teach subtopics or even through the re-reading of class notes.

Consider the different ways in which you can get students regularly retrieving the sorts of information exam questions will demand of them.

Try modelling how you would approach meeting exam questions yourself. Try a ‘beat the teacher’ activity. This is where you directly compete with students to answer an (unseen) exam question under timed conditions.

Exploring different ways of exercising working memory with students will help to show them how much they know. It will prompt them to think about how they can best demonstrate this to the examiner.

Getting creative

Get creative with the way revision is presented, developed and exercised in the classroom. Consider the different methods by which students can revise for your course’s various assessment objectives.

It may be that rote learning will work best for some students. However, on the whole, it’s good to encourage students to approach their revision more broadly, creatively and freely. This is so that they can develop stronger links between the different areas of information and assorted skills they’ll need to exercise in each exam.

Some ways of getting creative with revision content might include:

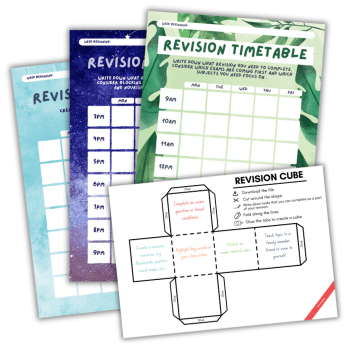

- Using design software or services such as Canva to create tailor-made revision materials

- Creating visually appealing revision posters that contain summaries, keywords, quotations and other important details

- Producing flashcards labelled with key concepts, ideas and keywords

- Making ‘revision cubes’ to help decide between subjects and topics that need revising

These creative tasks could be undertaken independently, in pairs or in groups. Giving students the chance to exchange knowledge and advice with their peers can create powerful collaborative learning spaces.

Creative tasks such as these can, admittedly, take a little time to initially set up – but once students have the right resources to hand, and possess a good understanding of the processes needed to achieve their end goals, creative tasks can become an enjoyable and valuable part of your exam preparations.

The revision poster and flashcards tasks can be helped along by providing students with lists of key terms, information sheets and other materials in advance.

Setting students resource creation tasks where the information is ready to be summarised and synthesised can reduce time spent on procrastination. It also lets those students with gaps in their knowledge get on with the business of filling those gaps quickly, potentially with help from their peers.

Timed practice

As students get closer to their exams, focusing their revision efforts on timed practice will be essential for their success.

There are many reasons why students may not feel they can excel in the exam hall. For some, simply being sat in the exam hall will be off-putting. Others may be dreading the need for them to focus their full attention on one exam question at a time.

We might not be able to make those anxieties disappear completely, but we can certainly increase students’ confidence in their ability to do what will be asked of them.

Get students regularly practising smaller, marked exam questions as a starter. Support them in peer- or self-assessing their responses with a student-friendly mark scheme.

Another way of getting students to write lengthier exam responses can be to practise writing composite answers in pairs.

Begin by pairing up students you think will work well together, then set the exam question (and if needed, model how you want the question to be answered).

The students then take it in turns to plan alternating paragraphs. Once each paragraph has been planned, have the students write paragraph-length responses using each of their partner’s plans, rather than their own.

Time this ‘response writing’ portion of the activity, and with the aid of a student-friendly mark scheme, ask each pair to consider if there’s anything else that can be added to their combined written answer.

Working in pairs like this can be a good way for students to confront tricky exam questions with support from peers.

The activity can also equip them with the means to assess the quality of their planning, train them in writing clear and coherent responses, and help them more accurately identify the assessment objectives of any given exam question.

Student-friendly mark schemes

Student-friendly mark schemes can support students’ understanding of precisely what they need to do for exam questions.

They can be created by breaking down a standard marking criteria and re-writing it so that each specific criterion is phrased as a straightforward question, instruction or statement.

My own approach when doing this is to ensure students can easily identify strengths, weaknesses and any areas for improvement.

I’ll colour code different areas of the mark scheme according to which assessment objectives each part applies to.

It’s important to use strategies that facilitate students’ revision of existing knowledge; prompt them to practice exercising this knowledge under exam conditions; and help them understand what they must do to achieve their final goals.

Some of these strategies may be better suited to the earlier stages of revision, whilst others should be reserved for the final run-up to exam day.

Remember that many students will fear the exam hall, and find exercising their existing knowledge during an exam extremely difficult.

Try to therefore provide different options during your lessons, and present students with a range of revision tools that can help them become more independent learners.

Meera Chudasama is an English, media and film studies teacher with a passion for design and research, and has developed course content for the Chartered College of Teaching.

Start encouraging better exam habits from Y7

If you want to ingrain good GCSE revision habits among your students, the real work should begin at KS3, advises Charlotte Lander…

Every teacher will be wearily familiar with the way some students in successiveb cohorts demonstrate the same bad GCSE revision habits and practices, year on year.

Could the key to tackling problematic GCSE revision habits lie in better preparation and instruction at KS3? Though if so, given the absence of any formal assessments between Y7 and Y9, how might this be built in, given teachers’ existing curriculum tasks?

Consider the synonyms for ‘revision’ you’ll find in a typical dictionary – ‘cramming,’ ‘rereading’… and cue the eye-rolling. Many, if not all teachers will at some point have taught students with an emotional attachment to their highlighters. You will have also taught others who preferg a more passive approach. This is usually signalled by a worrying lack of GCSE revision notes, cards – or indeed any preparation at all.

At its core, revision is the act of preparation. Successful GCSE revision, however, is both disciplined and purposeful. As teachers, we know that revision is ultimately a skill that we need to teach, model, practise and hone, just like any other. So it follows that the sooner we can start explicitly teaching those effective revision habits, the better.

Introducing our expectations

The question we then need to ask is when we should introduce our expectations for revision. If we stop to think about it, what does effective revision in a school setting actually look like? We might call to mind a Y11 student doing GCSE revision – creating mind maps and testing their peers on key information with the aid of flashcards. Or they might be quietly tucked away, busily jotting down knowledge from memory.

Yet both scenarios miss something important – the opportunities there are for students in KS3 to draw links between low-stakes retrieval quizzes, and the long-term retention of key subject knowledge needed for the exam room.

For many years, teachers have widely used retrieval practice in the classroom to improve learning through recall. Further to this, we continue to model metacognitive awareness; teaching students how to actively reflect upon their own thought processes in response to a task.

We explicitly teach these and many other effective classroom tools. However, we often leave revision to sit patiently waiting in the student’s toolbox until we’re finally ready to put it into action at KS4. This is alongside the assumption that students already have a cognitive blueprint for how to use it.

Strategy, mindset and behaviour

Often, one of the biggest challenges at KS4 (and KS5) is how to address the behaviour of students who rely on a brief last-minute scan of their notes. Or those who believe that cramming the night before is the key to success.

By this point, it’s usually too late for students to adopt and commit to a new way of revising. But if we can teach our Y7s that the recipe for successful revision incorporates strategy, mindset and behaviour, then we’re helping to build the foundations of long-term retention skills.

Possessing both the knowledge of how to revise effectively and the skill needed to put this knowledge into practice will enable students to experience a genuine sense of achievement in their learning.

A good starting point for this could involve organising workshops. Groups of KS4 students could, for example, organise and deliver revision-focused workshops to their KS3 peers across a range of curriculum areas.

These sessions might see the older students modelling their own revision habits and sharing their personal experiences. This might be how to:

- summarise topics

- identify keywords in a question

- maximise the capacity of their working memory

- use their knowledge organiser effectively.

If we can place explicit emphasis on students taking an active and effortful role in their learning, we can establish an important bridge between accountability and outcomes.

Revision redefined

If we could could start presenting revision as a form of ‘disciplined preparation’ that requires students to actively process, familiarise, decode and rehearse information, we’ll be creating multiple opportunities for students to ‘revise’ long before KS4. This is all without explicitly using the term itself.

Then again, we could argue that the term ‘revision’ is actually one that should be more commonplace in KS3 than it is currently. The naive assumption that revision is simply the act of ‘cramming the night before an exam’ or ‘rereading and highlighting notes’ can discourage students from applying the kind of (considerably more helpful) strategies they already employ daily in the classroom, all because of those limiting connotations often attached to the word ‘revision’.

Using the structure of Cornell Notes, you could task students in a Y7 English class with completing ten minutes of independent revision. Let’s say you prompt them to recall their knowledge of Stave 2 in A Christmas Carol.

They can spend five minutes retrieving their knowledge onto their notes sheets. Pupils can then spend the next two minutes familiarising themselves with the key events.

They can then spend the final three minutes reflecting on any knowledge they’ve missed and adding this to their sheets. Essentially, the students will have engaged with ten purposeful minutes of revision.

The activity itself might not be especially new or ground-breaking. However, it shows how straightforward the process of redefining students’ understanding of ‘revision’ can be.

Recognition and recall

While it’s all well and good prompting students to create mind maps or use flashcards at any Key Stage, if we aren’t teaching students how to actually engage with the content itself, then the blueprint will remain unfinished. More than this, we should expose students to the why.

Circling back to metacognitive awareness, it’s crucial for students to begin drawing links early on between what, how and why. We should expose them to why it’s so important to revisit knowledge often, and why transferring key information to flashcards will then allow them to use these at a later date as a cue for retrieving further relevant knowledge.

It’s one thing to create consistent opportunities to engage with effective revision habits. It’s quite another for students to understand why these are so valuable within the broader learning process.

Effective GCSE revision

A key aspect of effective revision is that it requires the student to take an active role in their learning. The goal is ultimately for students to distinguish between information they recognise and information they can recall. The latter will indicate a far greater sense of understanding.

The creation of ‘desirable difficulty’ is a fundamental element of good revision practice. It’s one employed in commonplace teaching strategies like spaced practise and interleaving.

Yet it can still feel much more comfortable for students to revise information they already understand. This creates a false sense of reassurance through the avoidance or dismissal of more challenging topics.

We must expose and confront these types of misplaced and ineffective revision habits at an early stage. We can model this self-awareness throughout KS3. This is by equipping students with the ability to hold themselves accountable for how to plan and structure considerably more effective revision habits.

Given that lack of formal examinations at KS3, it may feel too soon to introduce your students to revision-based approaches and strategies.

Yet if we want to capitalise on the success of independent study, then we should want our students to feel that we’ve equipped them with the tools and blueprint needed to actively implement much healthier revision habits. Ideally at a far earlier stage than the night before the exam…

Charlotte Lander is a teacher of English and psychology, and specialist in Talk for Learning.