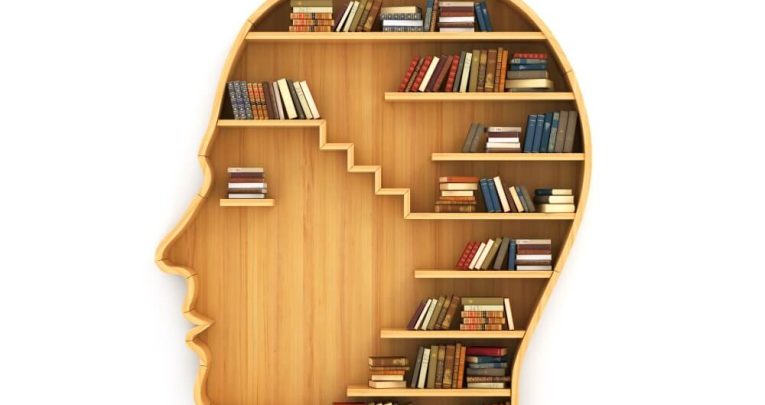

Bibliotherapy – The emotional and psychological benefits of reading

Gordon Cairns explores the practice of using books and stories in schools for therapeutic, rather than simply academic purposes…

- by Gordon Cairns

- English and forest school teacher

Having now been back in the classroom for a while, it’s become clear that the post-lockdown return to school has been somewhat traumatic for some of our students.

I recently found myself having to abandon two separate activities in one class after the young people struggled to stay on task – the class in question having seemingly reset back to how they were when they first arrived from primary school in autumn 2020.

One of the students asked me, “Why don’t we do what we did back at the start of term? You know – when you were reading to us?” This 12-year-old boy will have likely never heard of bibliotherapy (the use of reading materials for therapeutic benefit), but he was still able to recognise that something about being read to helped calm himself and his peers down.

Warmth and security

At present, research within this area is typically limited to why actively listening to a story, or reading quietly in the classroom is good for students’ mental health.

There are overlapping theories which support the feelings held by many practitioners that such activities help to benefit young people beyond their purely educational purpose. Others outside of teaching are also recognising bibliotherapy’s benefits.

Educational psychologist Dr Gavin Morgan believes that a number of elements contribute to the calming effect of reading to a class of students, which can take them back to the warmth and security of their early childhood.

“Bibliotherapy is probably atheoretical, but it does encompass a lot of different psychological approaches,” he says, positing that one of these is attachment theory: “Being read to takes us back to that early stage of our development, and is something we get from our caregivers. We can all remember our parents reading to us, so by its nature it’s a calming, attachment-building exercise.”

Where that attachment with a caregiver is insecure, a student may seek it with other significant adults in their life who can perform that traditional parental role of reading to them.

Morgan adds, “Attachment is vitally important, and for some kids, attachment to a teacher can be really strong where they have an emotional bond – especially if they don’t have a secure attachment elsewhere.”

De-escalation

Morgan goes on to point out that bibliotherapy contains some elements of cognitive behavioural therapy – a talking treatment which aims to reduce anxiety and depression. In his view, literature can give young people examples of life challenges they won’t have experienced yet, which are CBT-like in their potential to help de-escalate those problems and challenges they actually are experiencing.

“It’s all new to them; they don’t have a road map to life, so it takes some time to work things out,” Morgan explains. “However, a good story takes you somewhere else, sparking your imagination as you begin to visualise the narrative. For some children, this can be really effective in enabling them to perceive different perspectives and allowing them to see how people in stories solve dilemmas and work out problems.

“That can be really helpful for some children – allowing them to transfer themselves into situations, seeing characters brought to life solving difficulties.” A good story can further alleviate young peoples’ tendency to catastrophise problems and help teenagers put their personal lives into some sort of perspective.

“We know from working with adolescents that their social life is vitally important, but also the main thing that causes upset. A well-chosen story can show them kids working together to solve problems and de-escalate situations.”

As well as the positives relating to attachment theory and CBT, a book’s ability to take children to a calmer place offers some mental health benefits of its own:

“When we are reading, we are comfortable; we are quiet, we are focused, we are imagining. We are being involved, and we are actively listening. All of this generates that air of calm.”

No easy option

Yet despite all the benefits of active reading as a class, one barrier preventing educational professionals from embracing it wholeheartedly is the notion held by some that reading isn’t really teaching. There’s the perception that it’s somehow an ‘easy option’ – an idea Morgan is quick to refute.

“There is a pressure on teachers to get kids to work towards collecting evidence through reams of writing – but to me, that’s always a secondary issue.

“You can have difficulties with children if all you want from them is ‘product’, as that can lead to flashpoints in the teacher/pupil relationship. There may be no concrete written evidence to show when kids are responding to you and listening to you read, but they are learning.”

Morgan concludes that, “As a teacher, you have to be flexible and need different weapons in your armoury to keep kids on task and learning. Everybody learns in a different way, and reading should be a part of a good teacher’s skillset.”

Tried and tested

Keen to realise some of the wellbeing benefits to be had from bibliotherapy yourself? Start here…

1. Make reading rewarding I’ve come to realise counting is central to my own reading experience, from how many pages I’ve read in a single sitting, to the number of books I’ve read that month.

Target-setting can break long books into more manageable reads, while triggering our internal reward system. By noting how many pages or chapters are read each period, students can be encouraged to feel a sense of achievement – especially those for whom a narrative alone isn’t enough to keep them engaged.

2. Set the tone Try to create an environment that lends itself well to reading – ideally one with subdued lighting, plenty of ventilation and noise reduced to a minimum. If students are reading books of their own choosing, I’ll sometimes let them eat snacks or drink so that they associate reading with a pleasurable experience.

3. Don’t interrupt! Doing nothing might be anathema to most teachers, but for a session of bibliotherapy to work, teachers really have to take a back seat. If reading aloud, fight the urge to break out of the book to explain a teaching point, and don’t add a background commentary of events. Instead, model your own behaviour on that of your ideal cinema companion.

4. Allocate your time carefully I’ve found that it’s best to start a new book earlier in the day, when there’s greater tranquillity in the class unit. Once the narrative has captured their imagination, and they want to find out what happens next, this becomes less important (though creating calm after a PE class with the adrenalin still flowing may challenge even the most compelling narrative)…

5. Don’t prescribe This is one session where teachers can’t be prescriptive. You can’t force someone to enjoy a book, nor march up and down the classroom making sure all eyes are on the text. The pupils have to find the joy in reading naturally.

Gordon Cairns is an English and forest school teacher who works in a unit for secondary pupils with ASD; he also writes about education, society, cycling and football for a number of publications