KS2 Book Topic – Oliver and the Seawigs

There’s something in the water in Philip Reeve and Sarah McIntyre’s Oliver and the Seawigs, with mermaids, a talking albatross and some rather strange islands…

- by Sue Cowley

Oliver and the Seawigs tells the story of Oliver and his explorer parents. The family have just returned from their adventures travelling the world and Oliver is looking forward to settling back into their home. But when lots of islands mysteriously appear in Deepwater Bay, and Oliver’s parents go missing, he must head off on one more adventure to get them back.

Your children will love following Oliver’s fast-paced quest to rescue his parents. Along the way they will find out what the Rambling Isles are, and discover exactly what happens at the Night of the Seawigs.

Before reading the book, talk with your children about what it might be about: looking at the cover, what do they think is going to happen in the story? What could a ‘seawig’ be? What do explorers do and why do they do it? What kind of real and mythical characters do they know of that are found in the sea?

1 | Taking flight

Mr Culpepper is a Diomedia Exulans or, in other words, a wandering albatross. The wandering albatross has the largest recorded wingspan of any living bird – up to 3.5 metres – and spends its life on the wing, returning to land only to breed. It nests mostly on the remote oceanic islands and can cover huge distances, because of its great efficiency in the air. Use Mr Culpepper to inspire you to study how the wandering albatross has been depicted in literature.

After Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s poem The Rime of the Ancient Mariner was published in 1798, a number of superstitions grew up around the albatross.

In the poem, the bird leads some sailors out of danger, but after the mariner shoots the albatross, the boat gets stuck in becalmed water. The crew gradually go mad and die from lack of water, leaving only the mariner alive.

The phrase ‘an albatross around your neck’, meaning a weight or burden to bear, is derived from the poem. Read these famous lines from the poem to your class, talking about what they mean and the kind of images they create in the children’s heads.

Ask your children to think about how it would feel to be stranded on a boat in the middle of the ocean, with no water to drink.

Day after day, day after day,

We stuck, nor breath nor motion;

As idle as a painted ship

Upon a painted ocean.

Water, water every where,

And all the boards did shrink;

Water, water every where,

Nor any drop to drink

2 | A little fishy

Stories about half human / half fish creatures have existed for thousands of years. In Greek gods mythology, Triton is a merman, and mermaids are also associated with the Sirens of Greek myth, which lured sailors to their doom.

Some researchers believe that stories of this mythical being may have come from people mistaking sea creatures such as manatees and dugongs for mermaids. (Interestingly, both manatees and dugongs belong to the order Sirenia, more commonly called ‘sea cows’.)

Reread the section of Oliver and the Seawigs in chapter two, where Oliver first meets Iris. Now look at some stories and images of mermaids with your children, including modern day depictions such as Disney’s Ariel.

How are these mermaids different from Iris? Why do they think the authors decided to create a mermaid character who can’t sing very well, is rather plump, and has poor eyesight?

Create some mermaid pictures with your children. You could use painted fingerprints to create the tails. Alternatively, cut out shiny paper scales, and overlap these to create a three-dimensional effect.

3 | Hair-raising adventure

Reread the section in chapter three, where Iris explains about the Night of the Seawigs, which takes place in the Hallowed Shallows.

The winner is the Rambling Isle with the best seawig (literally a wig created from sea debris and worn by the island, which is itself a giant stone being often mistaken for a land mass), who gets to be Chief Island for the next seven years.

Get your students to design a poster to publicise the Night of the Seawigs, to encourage all the Rambling Isles to enter and visitors to attend. The children might like to include their own image of Dambulay, the previous winner, on their posters.

You could also get your children to create some seawig designs of their own, to enter into the Night of the Seawigs competition. These could be drawn or painted, or they could make three dimensional models with various bits of flotsam attached.

4 | The silly isles

In chapter five we discover that Mr and Mrs Crisp disappeared when they went to explore the island called Thurlstone. They felt it was the most interesting island, because of the ruined temple and stone heads on its summit.

They notice that the statues “looked a bit like the famous statues on Easter Island”, and imagine that the ruins are inhabited by “lost tribes, priest-kings and ancient wisdom”.

The Rapa Nui people created the Moai statues of Easter Island between 1250 and 1500AD. Talk to your children about the statues, and how they were created (for more detail, see wikipedia.org/wiki/Moai).

Share some images of the statues on Easter Island. Get the children to create their own Easter Island statues using clay or dough. Add sand or grit to give texture to the models. Find out how to do this here.

First-name terms

When Oliver first meets Stacey de Lacey, he blurts out “But that’s a girl’s name!” Stacey responds by saying that some names can be for either boys or girls, like Hilary or Leslie.

What other names can the children think of that could be used by either boys or girls? Can they think up surnames to rhyme with these names, as in ‘Stacey de Lacey’. Does it matter if a boy has a girl’s name, or vice versa? If the children think that it does matter, ask them to explain the reasons why they think this.

Take action

In chapter six, Oliver says that, “Years of exploring had taught him that you don’t solve problems by sitting around complaining about them. You have to do something.”

He tells the reader that this is how his parents had “saved him from the pterodactyl”. Get your children to write the story about what happened with Oliver and the pterodactyl, and how he was saved in the end. What did Oliver’s parents do to solve that particular problem?

5 | Exploring the illustrations

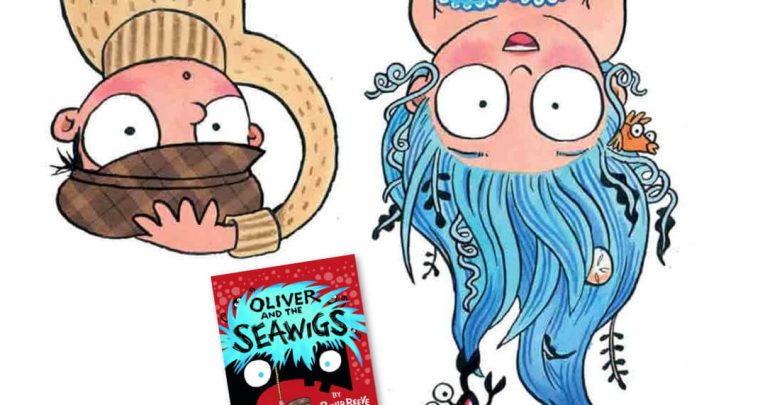

The illustrator of Oliver and the Seawigs, Sarah McIntyre, created the artwork using pen and ink. When drawing in pen and ink, the colour black has to do all the work – whether through using texture, shading, hatching, or areas of white or grey as a contrast.

Get the children to make some pen and ink drawings of their own, perhaps using the sea monkeys in the book as a starting point. You can find out more about pen and ink techniques at art-made-easy.com/pen-and-ink.html.

6 | The heart of the matter

The Wandering Isle called Thurlstone has an ‘empty heart’: both literally, and metaphorically. At the start of chapter nine we see an illustration of Oliver climbing up through the maze of gaps in its centre.

Because Thurlstone is empty, this allows Oliver to drop back inside him and tickle him with the peacock feather, so that he loses his wig. Use this idea of an ‘empty heart’ to explore how some metaphors work. Ask your children:

- When we say someone or something has an ‘empty heart’, what does this mean?

Now explore some other ‘heart’ metaphors: talk about what they mean and get the children to use them in a piece of writing, or in a poem. Ask the children to draw illustrations of these heart metaphors, to show how their meaning is linked to the images within them:

- Heart of stone

Synchronised swimming

Meet the collaborative authors/illustrators of Oliver and the Seawigs, Philip Reeve and Sarah McIntyre

What gave you the idea for the story? PR: I’d been thinking for a long time about writing a sea fantasy, with mermaids and mysterious islands, then Sarah told me she had wanted to be a mermaid when she was little.

How did you work together to create the story and its illustrations? PR: Our books are joint efforts. We come up with the characters and some of the things which are going to happen together, and then I start writing. I’m responsible mainly for the structure, and the choice of words. I read it to Sarah as I go along, and she makes suggestions. SM: After Philip wrote the story, we decided together how the main characters would look. We’ll often sketch out our ideas and compare them, using the best bits of each.

What medium did you use for the book’s illustrations? SM: I used old-fashioned dip pen and a little pot of India ink for the black lines. Then I scanned them and added the blue layer in Photoshop. We were very particular about the paper; we wanted paper that soaked up the ink and felt good between the fingers.

Could you say a bit about drawing the character of Iris? SM: People tend to draw their images from things they’ve seen already, for instance Disney’s Ariel when they think of a mermaid. You can instantly see that Iris doesn’t look like Ariel. She is wonderfully chubby, with amazing coils of hair that loop all over the place.