Trans children – How teachers and schools can support pupils

With the rapid rise in gender dysphoria referrals to the NHS among young people, it's time schools become more aware about the issues involved. Let's make a change…

- by Teachwire

What do you know about gender dysphoria? A little, probably, maybe even quite a bit, but how much training have you had in supporting trans children?

As far back as 2016, ATL (now NEU) was raising concerns voiced by teachers about the lack of meaningful, informed discussion surrounding gender identity in schools.

Part of the problem, of course, is that we’re still in the early stages of the conversation surrounding the subject.

JUMP TO A SECTION

- Where to find support and advice

- Case studies from teachers and parents

- Real students’ experiences

- Useful videos

‘Just a phase’

There remains a great deal of ignorance, naivety, fear and intolerance. Most of which comes simply from a place of unknowing. We’ve all heard the objections: boys are boys and girls are girls; it’s just a phase; ignore it and it’ll go away.

That same year, when a question on the entry form for Brighton primary schools was reworded, asking which gender (if any) each child most identified with, Conservative MP Andrew Bridgen called the move ‘ridiculous’. He argued that ‘schools should be teaching kids to read and write, not prompting them to consider gender swaps’.

But for many, this kind of thinking is not just outdated, it’s potentially harmful. The statistics for trans children and young people make for grim reading.

Pace, the LGBT charity, conducted a four-year study that found 48% of the young transgender people polled had attempted suicide. The report also noted that 59% of participants had thought about suicide, and 59% self harmed.

Around one in 100 children deals with gender dysphoria in some form, and the number of child referrals to the NHS is rapidly rising. In 2018-19 there were 2,590 referrals to GIDS.

This is not a remote or abstract issue; it affects many young people in schools who need our help.

A positive difference

Rather than waiting for a child, their parents or a staff member to come forward, there are calls for us to be proactive in educating staff and children about the diverse array of people in our world.

“It’s almost as if schools are frightened of the recriminations, so they try to sweep gender dysphoria under the carpet,” says Susie Green, Chair CEO of charity Mermaids UK.

“Half are good, half are appalling – there doesn’t really seem to be any middle ground. The good schools are fully behind it, while the bad ones often take a stance of ‘we’re not going to address this’.

“They’re dealing with a difficult situation that they’ve never come across before, and they probably aren’t aware of the legalities.”

Susie is always ready to step in should schools find themselves, knowingly or unknowingly, on the wrong side of the law.

This included correcting one headteacher who told the parents of a transgender pupil that if they insisted on letting their child present as a different gender, then the school would have to write a letter home to all the other parents, letting them know there was a transgender student in their son or daughter’s year group.

“I had to write to the school to tell them that would be illegal,” she explains. “It would not only be breaking data protection, but actively discriminating against this young person because of her gender identity.”

Miles apart

She also dealt with one case with two primary schools that were just a couple of miles apart in distance, but many miles apart in terms of their support of students.

“The child had been expressing as male since he was four, but his school refused to use his new name unless the mum got a deed poll done,” Susie says.

“But she couldn’t, because that would require her ex’s input, and she didn’t want to contact him because he was abusive. He hadn’t seen the children for years and she didn’t want him in their lives.

“So the mum started talking to the other nearby school, which said that not accepting the child for who he was would be damaging, and that if she wanted to bring him to their setting, he would be accepted completely.”

Schools should be aware that the Equality Act is very clear about this – any child dealing with these issues has the right to be known as, and to be accepted as, the gender with which he or she affirms.

“The bottom line is that if you have a child who has gender dysphoria, he or she does not need to have had any sort of treatment, or diagnosis,” says Susie.

“By denying trans children the ability to live and present as who they need to be, you’re telling them that something that’s so much a part of them is not allowed – that there’s something wrong with them.

“It’s essential that they are accepted, supported and loved, no matter what.”

Where to find support and advice about trans children

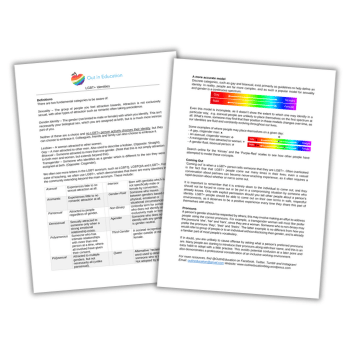

- GIRES – the Gender Identity Research & Education Society has a range of useful resources on its website, including a PDF about law and good practice for the transition of a pupil in school, and a map of organisations supporting trans and gender diverse people.

- Stonewall – check out Stonewall’s advice and resources for supporting trans children and young people.

- Educate and Celebrate – offers bespoke webinars on how to welcome trans, non binary and gender diverse people into your school.

- My Genderation – this film project celebrates trans lives and trans experiences.

- Mermaids – this charity offers offer gender-diversity training to schools and a range of useful resources, including the below video, which shows an assistant headteacher talking about how staff training, gender neutral uniforms and putting gender identity on the curriculum can help create a safe environment for trans children.

- NHS – take a look at the Gender Identity Development Service’s guidance for schools and hear from trans children about how they cope in school

Useful articles

- Understanding children’s atypical gender behavior

- What should I do if I think I might be transgender?

- The facts about transgender kids

- Name change letter if a parent is absent

Non-fixed mindset

So, how can we move into a position of acceptance and understanding? A good place to start is with the term gender dysphoria itself, which isn’t just “I want to be a boy/girl”.

It’s the opposite of euphoria, and so refers to any discomfort felt at the difference between your sex and gender. In other words, gender identity is complex and varied.

A 2012 report from Bath University on transgender adults found that 40% of participants had a constant and clear gender identity as a woman, and 25% as a man. But 23% considered themselves to be non-binary, while 3% said ‘other’, and another 3% ‘no gender identity’. 6% said ‘unsure’.

Kirstie McEwan, a psychosexual therapist who specialises in gender and sexual diversity, says that children start to exhibit gender dysphoria or variant behaviours as their self awareness develops, around the age of four.

“There aren’t many reliable statistics, but children who display this behaviour can go a number of different ways, especially by the time they start puberty,” she says.

“They may transition completely to the opposite sex, they might not. They may become more variant and fluid or remain as gay adults, rather than those with gender difficulties.”

Early stages

But even with the possibility that a child’s dysphoria might be temporary, this is no reason to disregard it as a phase, says Kirstie.

“The key is to support the child or young person at every stage to decide how they feel in moving forward. And in the early stages you’ve got to let a gender-variant child choose.

“In the early stages you’ve got to let a gender-variant child choose”

“And they may not know which way they want to go, and swing backwards and forwards, but if you try to force them into a new gender, that can be as harmful as keeping them in a gender.

“We’re going through a period in society at the moment where the binaries of male/female and man/woman are being thrown out the window. So, you need to be flexible and supportive of the choices that child makes, while educating the adults and children around her.”

What’s in a name?

Considering gendered language is another important factor. It can pigeonhole trans children, and reinforce stereotypes, as Rose Wheatley (name changed), head of an Oxfordshire primary, found through staff training with Educate and Celebrate.

“The support we received challenged a lot of our perceptions of the gender-specific language we use, such as ‘good girl’ and ‘good boy’. It taught us to be more diverse in the way we handle children,” says Rose.

“Gender-specific language fuels stereotypes. And we do this in schools all the time. We break out into gender groups, we provide sports based on gender.

“Now, I think we’re becoming much better at preventing ourselves from doing that, so the session was a really positive experience.”

“Gender-specific language fuels stereotypes”

Making mistakes

Rachel Dalloway (name changed), a head in another Oxfordshire primary, provided similar training for her staff through the charity Stonewall.

“We try to avoid saying ‘boys line up here, girls line up here’ or things like ‘I need a couple of good strong boys’ if something needs moving.

“But the biggest lesson for me is that you will make mistakes – you will use the wrong pronoun, for instance. You can get very anxious about this, but the important thing is to ask the child what they want, how they want to be treated and what they want to be called.”

This might be difficult at first, gender pronouns are ingrained in our lexicon. And we don’t really have a suitable neutral pronoun to use without sounding like a robot.

One nation, however, has solved this same problem. Rather than ‘hon’ (she) or ‘han’ (he), Swedish people can now use ‘hen’, after it was added to the dictionary in 2015.

This makes it possible to talk about or to a person without revealing gender – whether it’s unnecessary information, whether it’s unknown information, or if the person in question does not identify solely as one gender.

Transition

Even the word ‘transition’ has raised some debate. Think about it, if someone feels that they are a different gender to their biological sex, and wants to present as that gender, they probably don’t feel like they’re transitioning at all, merely presenting their true self.

We may still be heading into relatively unknown territory as a society, but at least this conversation is starting to take place in schools, businesses and in mainstream news.

And there are some incredible organisations and charities out there doing great work, where you can go for advice, resources and information.

Whatever fears we have of getting things wrong, this conversation must go on. It must get louder and it must get deeper.

And the only way we do that is through understanding and educating ourselves and others. Gender is varied, gender is fluid, and people are people. And all of us deserve acceptance, support and love.

Trans children case studies from teachers and parents

1 | Thomas, by Rose Wheatley

Amelia had considered herself a boy since the age of four. So, despite presenting as a girl – and being a girl on all our official documentation – Amelia returned to school after the summer break having transitioned to Thomas.

SLT informed all of the staff, and discussed with the class teacher how best to tell the children. We were conscious that it had to be low key, without fuss and that it was important to stick to the facts.

The children weren’t fazed at all. They were quick to adapt to Thomas’ new name and pronoun. A few parents of pupils from other years questioned what was going on, but the staff soon put a stop to any gossip.

“We were conscious that it had to be low key, without fuss”

We made no overt announcements, and this understated approach really helped to draw attention away from Thomas.

The Educate and Celebrate training on LGBGT+ introduced us staff to the appropriate language and all words on the gender identity spectrum, and it also challenged our views on stereotyping and the use of gender-specific language and colours.

Ten months on it is noticeable how little is mentioned of Amelia who became Thomas.

2 | Aaron, by Emily Edwards

My son, Aaron, is five now. He was born a boy, and is still a boy, but a lot of the time he wants to be a girl.

Ever since he could play dressing up he always wanted to be princesses, all his friends were girls and he was always playing with ‘girly’ toys. But halfway through Reception he started to be a bit more vocal about saying, “I want to be a girl”.

My initial reaction was shock, partly at myself for not having realised it. How could I not have seen this before? I spoke to his teacher, who is also the SENCo, and with whom he has a great rapport, and he’d told her the same thing.

“The school has been brilliant”

She immediately said that the school is absolutely accepting about any differences among students and she was very supportive.

Right now, a year later, he describes himself as ‘a girly boy’. We haven’t moved towards transitioning, and he doesn’t say he wants to go to school as a girl, or wear a girls’ uniform – beyond wearing a cardigan.

He tends to choose more girly clothes outside of school, or for non-uniform days, and it’s been no big deal.

The school has been brilliant. I said to staff that I very much feel like this is a journey. It might come to nothing, it might just be that he’s slightly more interested in ‘girly’ things.

It might remain fluid or it might lead to him eventually fully transitioning. For me, it’s just about emotionally and socially supporting him; the most important thing is that my child is happy.

3 | Olivia, by Lena Parker

When James was due to join our Reception class, his mum Lizzie came in to speak to me about how he was showing signs of gender dysphoria. At that point we knew absolutely nothing about it, but it’s been an incredibly positive story.

James was very focused on playing with girls and dressing like girls out of school. By the end of Year 3, he started talking about himself in terms of ‘she’.

What we didn’t know was that James had been living as a girl most of the time at home. Lizzie told us that things were bursting at the seams, and that her daughter wanted to come to school as her true self.

When James arrived on the playground as Olivia, I saw a huddle of children gathering and whispering, and feared the worst. But I soon realised I had no need to panic.

These children were asking a teacher if they could get some bits to make welcome cards for Olivia.

“It was just the most life-affirming thing”

Later in the year we knew things were going well when she put herself forward for school council election and her peer group voted her in.

For LGBT History Month, we did a thing in the playground where children dress in different colours to form a rainbow. And there was Olivia, holding a rainbow flag, just bombing up and down the playground while mum and dad watched.

It was just the most life-affirming thing.

Children’s names have been changed, as have those of some of the adults where noted.

Real students’ experiences

Trans sixth form pupil Morgan Rush, from Surrey, explains why making space for LGBTQ+ pupils in school is so vital…

We live in a time where support for the transgender community, and the LGBT+ community, is not only louder, but more tangible in its impact than ever before.

Many of us have the privilege of real, not theoretical, legislative and social change – but there are pitfalls, too.

Communication technologies have opened up avenues for support and education on things like gender identity, sexual orientation, transgender rights and discrimination at school that generations before us could never have imagined.

But they have also opened the door to a whole host of anti-LGBT+ hate and enabled the spread of ideologies that make it hard for young LGBT+ people such as myself to exist today.

Positive representation for trans children

The other hard part is figuring out that you’re LGBT+ in the first place. My rocky path towards realising I was not only transgender, but also a gay man, was one paved with self-doubt and hatred, fuelled by the world around me.

I heard horror stories about trans children my age being kicked out of their homes. I read reports concerning the murder of trans women around the world. There were constant reports about human rights violations in countries not so far away.

These, combined with my own experiences of hate crime, gave rise to a storm that followed me around, and closeted and displaced me from communities I wanted to participate in.

Helping others

I believe that the best way of helping LGBT+ young people is to use schools as a place of empowerment.

Participating in the Leaders in Diversity group at my school – an initiative that was rebranded and revamped with help from our most vocally supportive teachers – has enabled me to help other school students like me, and consolidate the pain I’ve associated with my own experiences of coming out.

Being one of the first trans students to come out at my school meant that, for all of the positive aspects of my school’s help, there were still teething issues with other students.

Allowing myself to help kids going through what I went through has been validating for my own experiences, while also giving kids access to help I didn’t have at their age.

Less education, more empowerment

Events such as School Diversity Week and LGBT History Month increase the visibility of LGBT+ role models like me and my friends within schools, among students and teachers alike. They show that there’s a place for us in the world.

Creating such spaces for young people like me is increasingly less about education, and more about empowerment. In a world that makes it easier for us to hide who we are, we need spaces where we can be whoever and whatever we want to be, without consequence or judgement.

Schools don’t always get it 100% right. But the act of making that space, of indirectly saying to LGBT+ students that there’s a place for them both within their own community and the world around them – that not only empowers us, but truly saves lives.

“That not only empowers us, but truly saves lives”

Showing support for LGBT+ students, even without full understanding of the issues they face, and being willing to learn and adapt to their needs, will help create the support and environments we need to thrive.

I’m glad that it’s easier to be an LGBT+ young person now than ever before – but it’s still not easy. With schools and students working together, we can create better environments for these students – ones that at many schools barely exist at all – and empower LGBT+ people as never before.

Joel Groves, who is transgender, explains why schools play such an important role in allowing pupils to be themselves…

Overshadowed

Looking back at primary school, I remember a mostly happy time. They’re some of the best days of our lives, after all. But for me, and so many other people like me, the joy of learning, making friends, story time and play are overshadowed.

You see, I’m transgender. I was transgender at primary school too, though I didn’t understand that fully yet. I’m well into my 20s now, and as an adult I love being transgender.

I love the pride I feel in myself and my community, I love being able to educate on trans inclusion, and I love being able to push for social change.

Being transgender is integral to my identity – it’s a big part of what makes me, me. I’m old enough now to embrace those things, and to meet the challenges that being an openly transgender person can bring.

Confused and scared

But when I was at primary school, I was none of those things.

I wasn’t proud, I wasn’t understanding of myself, and I certainly wasn’t equipped to face transphobia or social exclusion. I was just a confused and scared little boy trying desperately to pretend to be the little girl everyone else saw me as.

At home I was very lucky – my parents never tried to push traditional gender roles on me. I was allowed to wear what I liked and play with what I liked, and I was happy. But my experience in the classroom was less accepting.

Lack of inclusion

I loved my teachers and friends, but it was confusing yo-yoing from an environment that encouraged me to be myself, to one where everything was rigid and gendered.

My co-ed school felt highly segregated. Everything was ‘boys’ or ‘girls’, never either or both. I felt like a fraud when I was made to join the girls’ groups.

I have one very distinct memory of playing with dolls in the classroom one day and declaring confidently that I was going to be a daddy when I was older.

All the girls I was playing with laughed and my teacher corrected me: “Don’t you mean a mammy? Girls grow up into mammies, and little boys grow up into daddies.”

That left me feeling incredibly confused and ashamed. I certainly never said anything like that again.

Speaking up

It might sound like a small comment but I know that the following 15 years of my life could have been quite different if the response had simply been: “Really? OK!”

The message from everyone and every story book at school was clear: it doesn’t matter how you feel inside, you must be a girl. And I believed it.

Because of this, I didn’t have any understanding of being trans, nor the confidence to speak up and come out until I was 21, which is a really long time to hide such a significant part of who you are.

How to be an ally

But it didn’t have to be like that, and still doesn’t. I really believe teachers are incredible people who have the ability to transform young trans people’s lives. You don’t need to be any kind of expert either – you just need to be an ally.

One thing you can do is discourage unhelpful gender stereotypes. Being told repeatedly by peers and teachers at primary school that I should behave in certain ways because of my perceived gender was really damaging.

Segregating us by gender didn’t help either.

“I really believe teachers are incredible people who have the ability to transform young trans people’s lives”

It also would’ve been incredible for younger me to have been able to read books that feature gender-diverse children. The charity Just Like Us has a recommended reading list that might help you.

Diverse families

Talking about diverse families, such as having same-sex parents or a trans sibling, would’ve helped me loads too. And perhaps even organising some kind of Pride celebration during School Diversity Week, so that all pupils feel safe and welcome.

Your allyship won’t just help trans young people, but all children, to be equipped for our diverse world and show them that they can be themselves in school – no matter their gender identity or how they express it.

This will help ensure that when pupils reflect on their time at your school when they’re my age, their memories are nothing but shining and bright.

Joel Groves is a volunteer ambassador with Just Like Us, the LGBT+ young people’s charity that runs School Diversity Week, celebrated by thousands of primary and secondary schools every June.

Useful videos

BBC News’ Victoria Derbyshire speaks to two young trans children, to get an insight into what their lives are like and what help and support is available for other trans children in their position.

Leo, who is transgender, has experienced bullying in the past. Here are his top five tips for coping with bullying.

This video focuses on parents’ of trans children and their personal struggles to understand their child’s needs and find support for both themselves and their families.

In this heartfelt TED talk, Norman Spack explains how he helps trans children become who they want to be…