This New School Only Opened this Year, But Phil Beadle thinks he may have Discovered his Educational Paradise

It’s early days, but Christleton International Studio, which opened in September 2017, is functional and very friendly indeed

- by Phil Beadle

Teach Secondary readers may be aware of the concept of the Overton Window. This idea, which I first encountered in the pages of Owen Jones’ The Establishment, describes the range of ideas that are felt, at any one time, to be of the political mainstream. According to Jones and to anyone else half way sentient, the Overton Window has shifted somewhat rightwards over the last few decades.

Education has its own version of that window: the balance between what might be thought left leaning and right leaning ideas; between teacher as unimpeachable authority figure and teacher as part of the gang; between education as the acquisition of knowledge and that of skills (though this is a dichotomy I’ve summarily failed to understand since skills are complex interlinking pieces of knowledge applied, innit); between rules and rights; between the Devil and the deep blue sea.

Success, strictly

How we respond to and attempt to channel student behaviour is subject to political perspectives of course, and recently, this has been an arena of thought in which the Overton Window (or at least that which exists in sufficiently tangible manner as to have some effect on policy) has also moved, like the majority of currently fashionable educational ideas, rightwards.

How we respond to and attempt to channel student behaviour is subject to political perspectives of course, and recently, this has been an arena of thought in which the Overton Window (or at least that which exists in sufficiently tangible manner as to have some effect on policy) has also moved, like the majority of currently fashionable educational ideas, rightwards.

Influential voices construct superficially convincing, though decidedly Orwellian, rhetorical flourishes along the lines of freedom for students being a version of slavery; that in granting too much in the way of wiggle room behaviourally, we, as institutions, open the gates to our lessons being ignored and, as such, allegedly liberal behaviour policies end up illiberal in practice, as their consequence is working class kids failing.

Interestingly, many of those arguing for a more rigid approach to behaviour are Teach First ambassadors, some of whom may have themselves been educated in establishments in which student obedience is more a given than it was in the school they first started working in, and who, naturally, might seek to import the successful behaviour cultures from, for instance, the independent sector.

However, it is possible to learn lessons from the independent sector that are marginally more nuanced than, “Do what you’re told by your betters.”

An alternative model

Enter Kate Ryan. I first met Kate a number of years ago when she was part of the start up team of an independent school, Radnor House, in Twickenham. It was, and remains, the best school I’ve ever seen.

Enter Kate Ryan. I first met Kate a number of years ago when she was part of the start up team of an independent school, Radnor House, in Twickenham. It was, and remains, the best school I’ve ever seen.

We’ve formed a loosely philosophical friendship over those years, so much so that she has me teaching in her new school for 14-19 year olds this year. It is called Christleton International Studio; it is in Chester, and her philosophy for the culture in the school is influenced by her diverse background in state, independent, international and boarding schools across four different continents.

She’s worked in New York at policy level with global governments, with the OECD and innovative education groups across the Americas, and she combines this experience with a rootsy regional accent reflective of her own education at a comp school in Liverpool.

While Kate’s history takes in being part of corporate leadership in a global for-profit group and having created schools for some of the wealthiest cohorts in the world, her influences come from Freire, Giroux and Dewey.

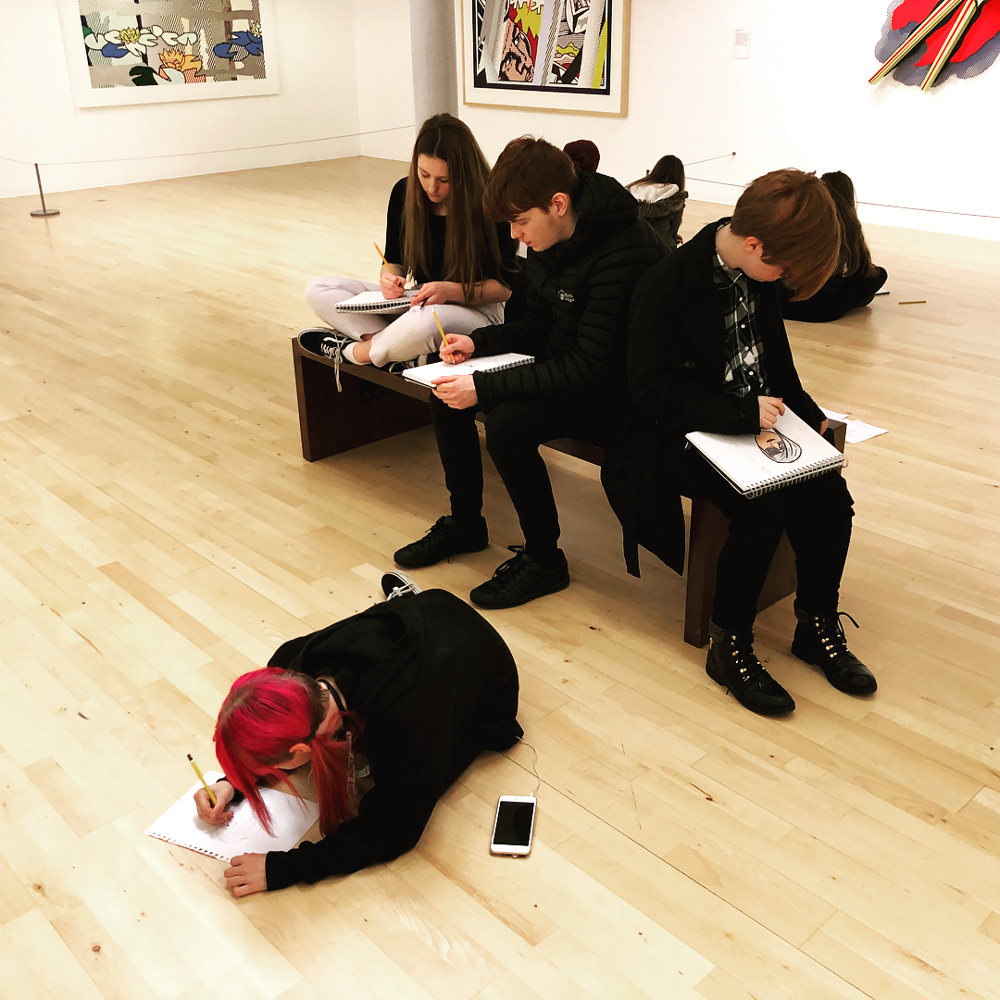

It is this somewhat surprising combination of experience and philosophy that drives what the school is trying to achieve. Kate wants it to offer state students similar levels of opportunity that one might expect from leading schools beyond the UK, and she cites AltSchool and Orestad Gymnasium in Denmark as particularly key influences.

‘Our aim is to offer an alternative to the typical model that is scalable, replicable and sustainable in order to narrow the gap regarding quality education offered to different groups in our society,” she explains.

“We are attempting a paradigm shift that that moves beyond the academic responsibility given to our students to a focus on the tone and depth of their relationships with staff. This must be complementary to high academic standards, and the school achieved full accreditation in the IB in two programmes before opening its doors – a feat unheard of this far.”

Relaxed and purposeful

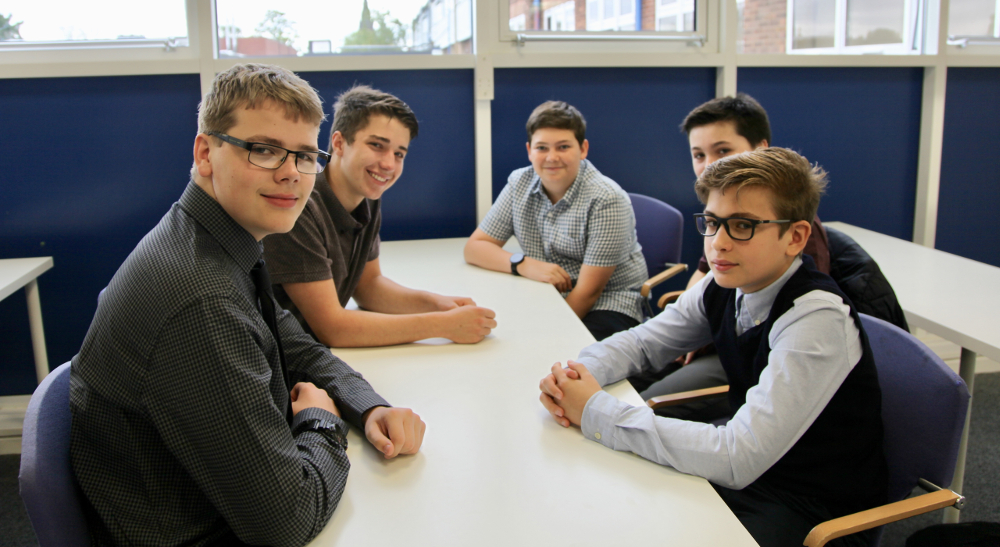

Historically, I’ve always responded to students asking me what my first name is with the answer, “Mister”; and in the first few weeks we all felt a bit weird with the practice, but it is part of a philosophy and once you have become used to it, it feels normal and nice. It places teachers symbolically at the side of students and is a part of the relaxed and purposeful groove of the place.

It is early days. The pedagogic culture is still forming. But after a term there, I’m happy to report that the alleged negative impact of having no identifiable proxies through which behaviour is managed has entirely failed to present itself. The school is functional and very friendly indeed, and student relationships with teachers, while slightly more informal, are in no way less effective or work focused than in normal schools. So much so, in fact, that it leads one to question normality itself.

The headteacher of Ressu Comprehensive in Helsinki, Erja Hovén, whom I interviewed in 2013, reported in these pages that she had been to British schools and had concluded, “It was so strict that even I was a little afraid. Everything in British education seems to be controlled, and being controlled does not make people happy.”

Christleton International Studio is notably happy, and this seems to me a rather sweeter state than being notably controlled. It is no Summerhill. Students follow GCSE and IB courses and are expected to work hard for themselves.

But if the see-saw of educational Overton Window seems to be rather heavily loaded by the idea that external control is just what children need, this school, at least, is attempting to put a tiny pile of pebbles on the side of relative freedom, mutual human respect, dignity and, yes, education as joy.

It is a version of paradise. Oh, and we need an English teacher.

Phil Beadle is a teacher, and the author of several books including Rules for Mavericks: A manifesto for dissident creatives (Crown House).