Teaching politics – satire gets students engaged, but the subject requires more

Satire provides an easy ‘in’ when engaging students with the study of politics, says Robin Hardman, but it risks undermining the subject’s most profound lessons

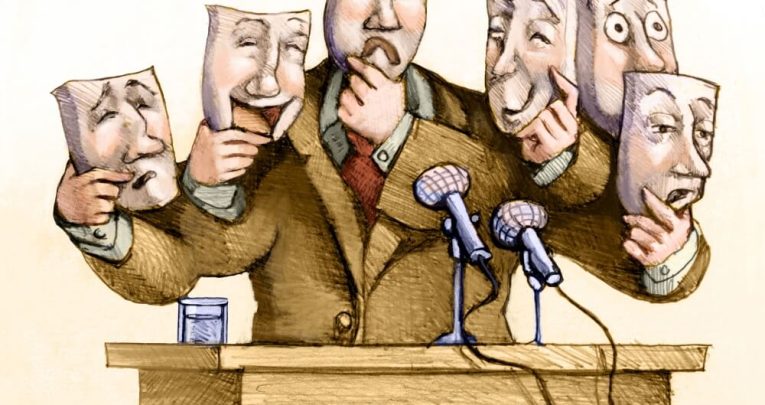

In an era when our politicians sustain panel shows and the meme industry by embroiling themselves in scandals on a near daily basis, it can be tempting to engage teenagers with politics through the medium of satire.

Sharing laughter and despair with our pupils at the depths to which our representatives have lowered themselves and our democracy can take on a cathartic quality, as well as helping to engage them in politics as an academic discipline.

‘Selling’ politics

But teaching politics isn’t like teaching any other subject. While all teachers have a responsibility to look beyond the narrow requirements of their curriculum and exam specification – formalised in references to fundamental ‘British values’ in inspection frameworks – this task weighs especially heavily in the politics classroom.

That’s because we’re helping to mould not just A Level pupils and future undergraduates, but active, engaged, and well- informed citizens who can enrich our democracy. Alongside guiding success in public exams, that must be our aim.

The Victorian critic John Ruskin famously deplored architectural short-termism with the waspish maxim, ‘When we build, let us think that we build forever.’ Well, when we teach politics, let us think that we teach politics forever.

In practical terms, this means infusing our teaching with opportunities for developing the knowledge and skills fundamental to meaningful democratic engagement – such as criticality of thought, dexterity of expression and deep, empathetic listening. It also means that we have to think about how we ‘sell’ politics, both to prospective pupils and when explaining to those who have already chosen to study the subject why our lesson content matters.

A wider significance

Politics may be by turns amusing and dispiriting, but we do our pupils and the subject itself a disservice if we neglect the wider significance of what we’re teaching. We’re teaching students about power, corruption, trust, policy, inequality, hope, truth, deceit, the histories of different societies and our planet’s future.

If our pupils are to become the active, responsible citizens we want them to be, then they will require an understanding of how these components interact with one another. They will need an awareness of how power can corrupt. They should be mindful of how the past can be appropriated to serve future goals, and be sensitive to the ways in which deceit can be disguised as the truth.

Rather than protecting our pupils from politics by indulging merely in satire, let’s instead unleash its full impact upon them. Teach students about suffering, and those policies that work compared to those that don’t.

Could you help save democracy?

Show them how powerful ideas can stimulate change. Impart the instinct to question at every turn. Explain that all opinions should be respected equally, but with the expectation that they should be substantiated with robust evidence. Organise debates; model attentive listening and mature rebuttals.

Encourage writing not just as a mode of assessment, but as a tool for self- expression and the development of reasoned thought. Analyse speechmakers’ intentions while appraising their delivery. ‘Why is she saying this to him?‘ ‘Why use that word rather than this one?‘ ‘Why even deliver that speech at all?‘

In doing so, you’ll soon encounter opportunities for satire – probably many, if our politicians carry on as they have been. You’ll find that your lessons see plenty of laughter and engagement, but also deep and meaningful learning.

You’ll observe your pupils developing the capacity to think for themselves, while also becoming adept at interpreting sources, constructing arguments, and defending their own opinions. And most important of all, you’ll hopefully find that one day, in the not-too-distant future, our democracy will have been enriched by your efforts.

Robin Hardman is head of politics at a school in south-west London and a freelance writer and author – his latest book, The Writing Game, is available now (£15, John Catt); follow him at @MrRobinHardman