Student progress – Why it’s best to assume the worst

Colin Foster makes the case for why assuming students will struggle is actually the most positive approach teachers can take in the classroom…

- by Colin Foster

When teaching, always assume the worst!

No, that’s not some world-weary call to pessimism, but actually a positive strategy for supporting students in the classroom. Because consider the problems that can arise when you don’t do this, and instead take as your starting assumption that things are probably, basically okay:

Teacher: Did you get on all right with the homework questions? Student: Er, yes… Teacher: Are there any you want to go through? Student: Er, no – it’s fine…

What’s going on here? The student clearly feels that ‘yes’ is the expected answer to the first question, but having said that, they’re then more or less forced into answering ‘no’ to the second. Any problems they might have experienced are buried, and consequently go unresolved.

The student saves face, and the teacher may genuinely think that all is well, and so move on – but learning doesn’t happen, and is in fact blocked. It’s akin to quickly asking a class, ‘Any questions?’, pausing for a microsecond and then saying ‘No? Okay, good!’ before swiftly moving on.

It’s usually unproductive, and simply ensures that any potential difficulties are swept under the carpet.

Here comes trouble

A much better approach is to assume the worst, to the point of setting up total failure as the starting point. Then, if necessary, the student can be in the happy position of bringing you good news, which gives the impression of placing them in a more powerful position.

Let’s imagine that same exchange again:

Teacher: Those homework questions were hard. Did you manage any of them? Student: Yes, I did the first one, but I couldn’t do any of the others. Teacher: Okay – do you want to go through the others? Student: Yes please.

This time, we’ve made it easy for the student to admit their difficulties. There’s no pretence around everything being fine when it isn’t, and no shame in the student admitting to having problems, as that’s clearly the teacher’s starting assumption. It takes no longer to frame things this way round, but makes it so much easier for the student to be honest.

Paradoxically, it’s also much more positive in that the student is constantly exceeding the teacher’s expectations – ‘You managed question 1? Well done! Now, let’s look at the others…’

High expectations

We’re often told of the importance of setting high expectations. While there is certainly truth to this, if it simply means living in an alternate reality (‘I’m sure you all managed those questions without any problems, didn’t you?’) then what does it achieve?

It’s far better to set challenging tasks and assume students will struggle with them (‘If it were easy, I wouldn’t have bothered wasting your time by asking you to try them’).

There’s no point in framing the situation with positive, leading questions that give the teacher a false sense of security regarding their students’ capabilities, only to then have that façade come crashing down once the next controlled assessment takes place, or when those skills are tested in some other context.

Every counsellor knows that if they ask a client ‘Did you have a good week?’ they’re more likely to get a positive response, even if their week was actually horrendous, because it’s a leading question that doesn’t communicate a strong interest in hearing the truth. Instead, a more neutral question like ‘How was your week?’ is much more likely to elicit an honest response.

The same applies in the classroom. We want to avoid fakery and being told what we want to hear. Instead, we have to probe for the problems, the difficulties, the things that make no sense to the student, and make it easy for them to tell us those things.

Instead of asking ‘Any questions?’ we could ask, ‘What questions do you have?’ so that it’s clear from our entire stance that questions are something we welcome, not an inconvenience. Only then will we put ourselves in a strong position to help students move forwards in their learning.

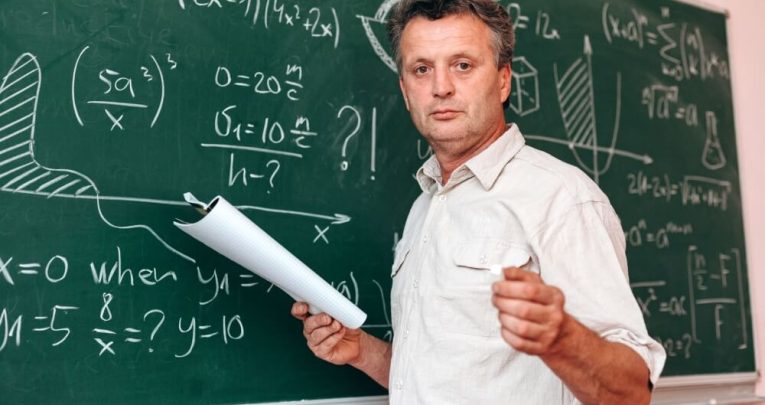

Colin Foster (@colinfoster77) is a Reader in Mathematics Education at the Mathematics Education Centre at Loughborough University. He has written many books and articles for mathematics teachers – find out more at foster77.co.uk