Ofsted Inspection Framework – Pros, cons and advice from experts

The Ofsted Inspection Framework allows schools to take fundamental steps forward in developing best practice, but are there downsides too?

- by Teachwire

What is the Ofsted Inspection Framework?

The Ofsted Inspection Framework, also known as the Education Inspection Framework (IEF) lays out how Ofsted inspects England’s schools, academies and early years settings.

When was the new Ofsted Inspection Framework introduced?

The Ofsted Inspection Framework has been in use since September 2019.

JUMP TO A SECTION

Ben Fuller, lead assessment adviser at Herts for Learning, explains how the Ofsted Inspection Framework allows schools to take fundamental steps forward in developing best practice…

For a number of years, in many schools, assessment practice was driven by one key question: ‘What does Ofsted expect us to do?’. And more often than not, this led to the word ‘assessment’ being seen as synonymous with ‘data’.

The 2019 Ofsted Education Inspection Framework represented some real shifts (for the better) in the inspectorate’s approach to assessment. It opened the door for schools to take some fundamental steps forward in developing assessment practice.

Assessment

There are a number of key paragraphs in the School Inspection Handbook that relate to assessment. I shall explore a few that I think are particularly significant. Firstly, regarding the implementation of the curriculum:

“The most important factors in how, and how effectively, the curriculum is taught and assessed are that: teachers check pupils’ understanding effectively, and identify and correct misunderstandings… teachers use assessment to check pupils’ understanding in order to inform teaching.”

In relation to the school’s use of assessment, the handbook states:

“When used effectively, assessment helps pupils to embed knowledge and use it fluently, and assists teachers in producing clear next steps for pupils.”

Looking at these points, we can see a clear emphasis on what is going on in the classroom. So we need to ask ourselves the questions, how well are teachers using formative assessment techniques to:

- find out what children already know so that they can build on this

- unpick children’s misconceptions

- check learning within (as well as at the end of) lesson

- provide effective feedback to move learning forwards

Evidence

In addition to these points about classroom assessment, the handbook says that inspectors will use to gain evidence about curriculum implementation “discussions with curriculum and subject leaders and teachers about… their view of how those pupils are progressing through the curriculum”.

So we also need to ask this additional question: how do teachers (and subject leaders) evaluate whether children are where they should be in their learning journey through the school curriculum?

In answering that last question, though, we need to take note of the key message that data collection and analysis should not create excessive or unnecessary workload.

It’s not that practices such as tracking pupil attainment over time need necessarily disappear altogether, but they must be proportionate and purposeful. More on this later, but for now let’s keep the focus on the formative.

Formative assessment

The first four of the above questions are all about formative assessment, while the fifth focuses on the summative. For me, that ratio of 4:1, formative to summative, is a good guide to how we should be investing our assessment energy.

Overwhelmingly, we should focus on the formative, as that is where the greatest benefits to learning will lie.

There is plenty of evidence that formative assessment, or ‘assessment for learning’ (AfL) if you prefer, can have powerful impact on learning, when its core principles are at the heart of teachers’ practice.

“We should focus on the formative, as that is where the greatest benefits to learning will lie”

But AfL can sometimes be misinterpreted when it comes to classroom practice or school policy. It can end up being distilled into a set of strategies or rules that might be somewhat divorced from the core principles. As an example, let me focus on one area: feedback.

Feedback

Effective feedback, whether it be written or verbal, should move the learning forwards. It needs to identify what has been done well, what needs improving and how that improvement can be achieved.

In some schools, marking/feedback policies might dictate particular practices, such as using particular colours of highlighter pens, or giving ‘three stars and a wish’ comments.

But I would argue that all of those things are peripheral. The most important thing to consider is the impact of the feedback: has it caused thinking to take place?

The content of the feedback is crucial, as is the timing. It should be focused on the intended purpose of the learning, and the more immediate the better.

And it’s important to note that feedback might need to look different according to the learner.

“The most important thing to consider is the impact of the feedback”

So let’s not worry unduly about consistency in terms of what things look like. School policy can, and should, dictate consistency in terms of the principles to which all staff are expected to adhere, but should allow the flexibility for teachers to use their professional knowledge of the child.

This is so they can give the feedback that is going to be of greatest benefit to that individual at that point in time.

Feedback to a novice learner may very well look quite different to that which is given to a learner with a more advanced understanding of a particular concept.

For some learners, a coaching approach might be hugely beneficial, although a learner already needs a pretty good grasp of where they are in their learning and where they want to get to for a coaching approach to be effective.

Prior knowledge

To return to my earlier questions, effective techniques to gauge children’s understanding of subject content prior to teaching a unit of work, during the teaching and at the end are also very important.

Knowledge organisers, concept cartoons, mind maps, true/false quizzes and so on can all be useful tools to use as starting points for class discussion. They can illuminate areas of the subject where:

- knowledge is already secure

- misconceptions lie

- the knowledge is lacking

Such techniques are particularly useful when there is a spiral curriculum in place. For example, children will have learnt about the topic of ‘animals including humans’ during KS1. They’ll then likely revisit this topic at various points in KS2. It’s important to ascertain what has been remembered from the previous teaching when planning your next unit.

You can’t rely on a simple record of what was taught, or even what appeared to have been understood, in a previous year as a guarantee that those concepts made it into the long-term memories of all the children.

Good classroom assessment techniques play a vital role here.

Hinge point question

During teaching, the idea of the ‘hinge-point question’, is a hugely powerful strategy. It enables you to make evidence-based decisions about the direction of the lesson.

Time spent devising really good hinge-point questions to use in lessons is particularly worthwhile. As Dylan Wiliam explains, the trick to devising good multiple choice hinge questions is to consider the possible misconceptions that different learners may have.

The wrong answers should be those typically given when common misconceptions are held. The question should be designed so that it is extremely unlikely that someone could arrive at the right answer but for the wrong reason.

End-of-unit assessment

In terms of end-of-unit assessment – the means by which you seek to determine how well the students have learned the material – think about:

- the particular areas of knowledge, skills and concepts that we wish to assess

- the range of approaches that we might use as vehicles for the children to demonstrate their learning.

On the first of those points, this is where curriculum mapping is essential. Across your school, is there a clear map in place that shows in which year groups you expect children to learn key concepts?

Are there particular milestones, in terms of skill progression or areas of knowledge?

For example, which key skills do you expect children in Y4 to develop in art? How does this build upon their Y3 learning? What are the expectations of a Y1 child in geography? These will vary from school to school.

Tim Oates encourages us to teach fewer things in greater depth. Each school will make different choices about what to prioritise in its curriculum.

The curriculum choices you make will determine the key milestones upon which your summative assessment should focus. They will probably also determine the choices you make about what data to collect.

Flexibility

In terms of the range of approaches, the only limit is your imagination. Whether you ask your children to produce a dramatic presentation, a cartoon, a poem, a website, a poster, a podcast, an assembly, a piece of writing or even to take a good old-fashioned test, one thing we do need to ensure is that we are maintaining the integrity of the subject.

Cross-curricular work can be wonderful, but we need to be clear about the focus of our assessment. If we ask our children to write, for example, a diary entry or letter from the perspective of a particular historical character, are we assessing it from a literacy perspective, or looking for accurate historical knowledge? Or both?

Supporting role

There is a real opportunity here for us to refocus our thinking on the assessment that goes on in our schools. Its place is to support and inform our teaching of the curriculum, not to drive it.

Our curriculum should not be determined by what’s going to come up on a test. The curriculum must come first and should be the master. Assessment should always be the servant.

“The curriculum must come first and should be the master”

Summative assessment

So what of summative assessment and the extent to which subject leaders in schools need data to be able to demonstrate the progress pupils are making across the school?

The School Inspection Handbook indicates that inspectors will consider whether data collections are:

- proportionate

- represent an efficient use of school resources

- sustainable for staff

Crucially, any data collection should serve a purpose – it should inform clear actions. For example, it should indicate areas of the curriculum that require greater teaching focus or a professional development need. It might indicate a groups of pupils that need further support, and so on.

I encourage school leaders to think about your current data collection practice and carry out a quick cost/benefit analysis. Consider how much teacher time and energy goes into each data collection, and consider what benefits they bring. Do the benefits justify the costs?

Data drops

The handbook mentions that inspectors will evaluate how assessment is used to support teaching. However, they will also be looking to see that assessment practice is not substantially increasing teacher workload. The Making Data Work report recommends a maximum of three ‘data drops’ per year.

It is particularly important to note the following, from the handbook:

- Inspectors will not look at non-statutory internal progress and attainment data

- Inspectors will be interested in the conclusions drawn and actions taken from any internal assessment information, but they will not examine or verify that information first hand

This is significant. In the past, data has been used for multiple (sometimes conflicting) purposes. But if the internal data is exactly that – internal – we can encourage teachers to be brutally honest in their assessments without worrying how it might look to others.

Indeed, we need this brutal honesty. The fundamental point of the assessment is to provide an accurate basis for decisions.

“We can encourage teachers to be brutally honest in their assessments without worrying how it might look to others”

If boys’ standards in maths in Y4 are slipping a bit, or girls’ progress in reading across the school is not as strong as you would hope, then leaders need to know about this. They can then consider what actions may be required. This might be resourcing, training, targeted support, and so on.

Of course, understanding how well a subject is taught across the school is far deeper than just analysing numerical data.

Observing the teaching, talking to the pupils about their learning and looking at the work they produce are all essential.

Teacher wellbeing policies

Ofsted’s Inspection Framework recognises teacher welfare, but how can you gauge whether your policies are fit for purpose? Dawn Jotham from EduCare investigates…

The 2019 Ofsted Inspection Framework had three key changes from its predecessor. These were a greater focus on equality and diversity, expanding the curriculum to educate the ‘whole’ child, and an emphasis on teacher and staff wellbeing.

Significantly, the latter heeded the call from those in the education sector about unmanageable teacher workloads, stresses, and detriment to teacher welfare.

The result? An expansion on wellbeing from pupils to also include teachers and staff – a move that hopefully made inroads to addressing the teacher recruitment and retention problem.

This was undoubtedly a welcome addition to the inspection framework. But these changes also pose some challenges for schools.

Namely, how can you improve staff morale as well as effectively gauge, demonstrate and evidence to inspectors that you have stringent measures in place to support teacher wellbeing or improve staff morale?

Criteria

The Ofsted inspection handbook says that teacher wellbeing is judged as part of the leadership and management criteria. Those striving for an ‘outstanding’ rating will be assessed on the following basis:

- The school meets all criteria for good in leadership and management securely and consistently

- Leadership and management are exceptional

- Leaders ensure that teachers receive focused and highly effective professional development. Teachers’ subject, pedagogical and pedagogical content knowledge consistently build and develop over time. This consistently translates into improvements in the teaching of the curriculum

- Leaders ensure that highly effective and meaningful engagement takes place with staff at all levels and that issues are identified. When issues are identified, in particular about workload, they are consistently dealt with appropriately and quickly

- Staff consistently report high levels of support for wellbeing issues

Duty of care

Schools must demonstrate that staff are protected from bullying and harassment, and that teachers’ workloads are effectively managed.

To implement best practice, pastoral care specialists and senior leadership teams should regularly conduct reflective exercises that help identify key strengths and weaknesses with regards to teacher wellbeing. This should highlight areas for improvement.

“Schools must demonstrate that staff are protected from bullying and harassment”

Questions to consider

With this in mind, the following questions will help improve your provision of staff and teacher wellbeing, and strengthen your evidence base during inspections:

- Are there robust policies and procedures in place that protect staff and pupils from bullying and harassment?

- Clear guidelines are an effective way of communicating your school’s values and code of conduct.

- Formal policies and procedures provide a tangible way of demonstrating the steps taken to support teacher wellbeing.

- Does your school have an in-depth induction process?

- An in-depth induction process supports the policies and procedures that establish school norms and safeguarding processes.

- The central record which Ofsted will look at during inspections should include a list of staff who have completed their induction.

- Does your school provide teachers with a mentoring programme?

- Mentoring programmes encourage knowledge sharing and best practice among staff.

- Extend mentoring beyond staffing peers to increase engagement and guidance with governors.

- Do staff feel listened to and involved in shaping initiatives from the senior leadership team?

- A key judgement from Ofsted assesses the ways in which leaders engage with their staff.

- Clear lines of communication between leaders and staff fosters mutual respect and encourages greater engagement.

- Do teachers feel safe?

- Ofsted will assess whether schools have created a positive and respectful culture.

- This references spikes in bullying, peer-on-peer abuse and discrimination.

- Establishing robust policies and procedures will help teachers feel safe and provide clear reporting instructions.

Convincing and evidenced

The wellbeing of teachers and staff in schools is obviously central to the efficacy of the learning environment for pupils and sustainability of the broader school community.

Leaders not only have a duty of care to make sure teachers and staff are well supported but also that schools are compliant with Ofsted’s EIF and ready to demonstrate they are adhering to the guidelines in the most convincing and evidenced way possible.

Dawn Jotham is the education product development lead at EduCare. She has held the positions as head of year and lead for pastoral care, and has a masters in childhood and youth studies.

Criticism of the Ofsted Inspection Framework

Frank Norris MBE is a former senior HMI responsible for framework development at Ofsted. He thinks that Ofsted needs to do some soul-searching to make its inspection framework genuinely helpful…

When the Times Education Commission published its ‘Bringing Out the Best’ report in June 2022, I welcomed the damning statements about the inspectorate from a wide range of voices.

These included Dame Alison Peacock, the chief executive of the Chartered College of Teaching. She compared Ofsted to a reign of terror. Professor Tim Brighouse felt the inspectorate had ‘effectively created the equivalent of a sheepdog which is eating their own flock’.

Done to schools

Despite modifications to the process of inspection over time it is still largely done to schools. Any shift towards greater collaboration between the inspectorate and those it inspects would probably need to include reform of the grading and regularity.

I’ve thought for some time that HMI undertaking short, planned visits to schools every three or four years where they share their observations in a short note would suffice. The assumption should be that all schools are effective, unless we find out otherwise through inspection.

The short note would indicate whether a full inspection might be helpful in securing further rapid improvement. I believe that less than 10% of existing inspection activity would be required under this system.

“The assumption should be that all schools are effective”

The Commission also proposed that Ofsted works more collaboratively with schools to secure sustained improvement. It also proposed that Ofsted uses a wider range of measures such as wellbeing, school culture and attendance to determine effectiveness. This could be done via a ‘report score card’.

This suggestion is helpful. But it needs to include a sufficiently wide range of reliable data and robust information to help parents and carers understand the strengths and relative weaknesses of the school.

Right now, despite slight changes to the DfE standards website, it remains too heavily weighted towards some factors that are not entirely in the control of the school.

The new report score card, on the other hand, would enable parents to select the aspects of school life they consider to be most important. This is rather than largely relying on an overall Ofsted grade.

Implementing recommendations

So, well done to the Commission. It produced a more ambitious and thought-provoking statement on the future of education in England than the government’s 2022 Schools White Paper.

Its recommendations for improving inspection are timely but it will require some real soul searching at Ofsted to embrace them.

Any review of the inspectorate needs to consider its negative impact on recruitment and retention of staff including school leaders. It also needs to consider the impact on the culture of ‘Ofsted-centric’ schools and on innovation and curriculum change. It should also consider the broader impact on schools facing the most challenging circumstances.

Frank Norris MBE was the CEO of the Coop Academies Trust for six years. He is currently the education adviser to the Northern Powerhouse Partnership. He’s also the independent chair of the Blackpool Education Improvement Board.

Deep dives

Education consultant and former Ofsted HMI Adrian Lyons discusses whether subject ‘deep dives’ betray the government’s curriculum priorities…

Ofsted predicates its curriculum discussions on the principle that choices must be made, and that a rationale must always be given for how those choices are ultimately arrived at.

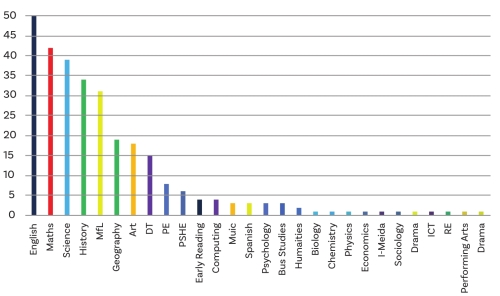

So what is Ofsted’s rationale for its curriculum deep dive choices? Research carried out by former HMI and Ofsted senior leader Adrian Gray sought to show which subjects Ofsted focused on the most during the autumn of 2021.

Largely, individual lead inspectors made those curriculum choices, with little to no centralised strategic thinking behind them.

Where there has been direction from the centre, it has largely resulted in a narrowing of the subjects that can be chosen for Ofsted enquiries into quality of education.

So it was that in January 2022, Ofsted quietly dropped both PHSE and citizenship from the pool of subjects that it could potentially inspect under its quality of education judgement.

Causing problems

The rationale for this is difficult to pin down. The organisation’s argument is that PHSE already plays an important part within an inspection’s personal development judgement. It also isn’t a national curriculum subject.

That may be true, but then neither is religious education, which is subject to deep dives (albeit rarely, as shown in the graphic). On the other hand, citizenship is a standalone national curriculum subject that schools have sorely neglected over the past decade.

I fear that the relative lack of RE deep dives in secondary schools is due to the strong probability that statutory requirements wouldn’t be met. This would then cause problems for the whole quality of education judgement.

I used to joke with other HMI that if you wanted to be sure of getting evidence for an ‘inadequate’ judgement in a secondary, you’d select RE, PHSE and citizenship for deep dives.

All three have become overlooked, yet nonetheless vital subjects for preparing young people for life in modern Britain.

“If you wanted to be sure of getting evidence for an ‘inadequate’ judgement […] you’d select RE, PHSE and citizenship for deep dives”

Narrow spectrum

Internally, the range of subject areas considered ‘worthy’ of Ofsted’s attention has been steadily reduced. The upshot of this is that in 2020, the highly popular secondary school curriculum area of economics, business and enterprise was axed altogether.

It’s not simply the case that an over-emphasis on knowledge to the exclusion of other skills has been controversial. The problem is more that the knowledge selected forms a very narrow spectrum. In this ongoing battle between ‘knowledge’ and ‘skills’, important aspects of personal development have lost out.

I agree entirely with Her Majesty’s Chief Inspector, Amanda Spielman, that a child growing up in Grimsby should have the right to the same curriculum as a child growing up in Chelsea.

I would, however, argue that powerful subject knowledge only forms part of a good quality education, and not – as Ofsted has been so keen to promote since 2019 – the whole of it.