‘Fake News’ Is An Old Story, But Today’s Students Might Need Different Skills To Spot It

Pupils need to look beyond the social media echo chamber, says Andrew Shenton

In March 2017, the BBC reported comments made by Andreas Schleicher, the director for education and skills at the OECD. He had drawn attention to the importance of schools teaching young people about how to identify so-called ‘fake news’ and the need for pupils to look beyond the social media ‘echo chamber’, where they may see only views like their own.

Mr Schleicher’s intervention helps raise the profile of two issues that are particularly challenging but his words perhaps imply – quite incorrectly – that schools have yet to give an appropriately high priority to the skills and practices involved.

It has long been recognised that a research assignment should require pupils to consult sources that expose them to contrasting perspectives, and the importance of emphasising the need to evaluate information rigorously has been a consistent message for many years.

As far back as the early 1980s, Michael Marland argued that pupils should consider a range of selection criteria, namely the information’s scope, suitability, relevance, authority, reliability, up-to-dateness, accuracy, bias and level, when examining individual resources.

Marland’s ideas were very influential, laying the foundations of principles that would underpin information skills teaching programmes for the next two decades.

The frameworks exist

More recently, evaluative skills have assumed added significance with the arrival of the internet, which provides easy access to much untrustworthy material, and with the growth of social media.

Today, frameworks teachers can employ with pupils to appraise information include the 5Ws of Web Site Evaluation and the CRAAP Test. My experience tells me that principles which can be assembled in a succinct abbreviation or irreverent acronym are more likely to be remembered by pupils.

There is, though, a danger that youngsters who embrace such frameworks then impose them mechanically, in all independent learning activities. Let us ponder on some pertinent scenarios.

Whilst in most circumstances pupils should seek material that is free from bias, on occasion they may be looking into the arguments of a particular pressure group and information preaching a certain viewpoint may be welcomed. Inaccurate content, too, may be sought if the reader is looking to determine the prevalence of a misconception.

There may also be instances where old, apparently outdated material is needed in order to gain insight into man’s state of knowledge at a certain time. The challenge for the youngster lies in applying the fundamental evaluative principles suitably in a given situation. As well as adopting particular quality criteria, pupils will give thought to relevance factors which may be equally important in their own circumstances.

Keep them critical

In addition to assessing specific examples of flawed information and isolating its deficiencies, pupils can learn much from ‘textbook’ cases of how individual authors have evaluated the information presented by others. However, attempts to abstract the key criteria and derive new frameworks from them are often too rooted in the original context, and pupils should think of further concerns that need addressing in different scenarios. If we are to encourage true critical thinking on the part of pupils, we must seek to promote critical thinking in relation to the tools available.

Whether the teacher’s concern lies in fostering ‘critical thinking’, addressing the problem of ‘fake news’, countering the untrustworthiness of social media posts or responding to the lack of quality controls on the web generally, many suitable frameworks already exist for evaluating information.

Even some of the old models retain their relevance today as pupils strive to uncover ‘the truth’ in the situations in which they find themselves. The long established evaluative skill of comparing material from different sources is as important today in exposing ‘fake news’ as it has ever been.

The key tasks for the teacher lie in presenting their preferred framework in relevant modern contexts, perhaps framed in terms of a current news story, and devising imaginative activities that engage youngsters on several levels.

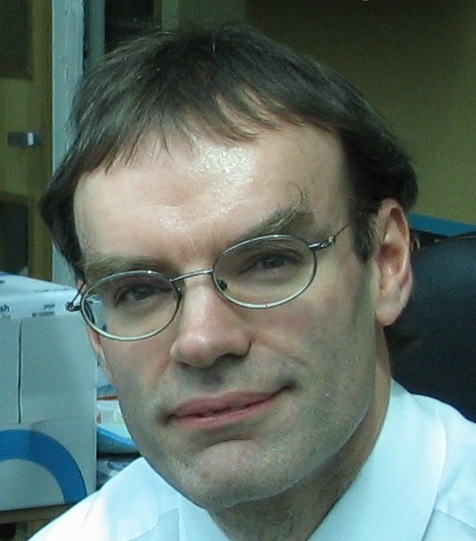

Dr Andrew K Shenton has taught primary and secondary aged pupils and lectured to undergraduate and postgraduate students at Northumbria University.