English literature – How to banish those GCSE exam fears

There’s fear in the air ahead of this year’s English literature exams which we need to dispel, writes Jennifer Hampton…

We’ll often discuss fear in English literature classes – but as students across the country embark on the first full set of English literature papers since 2019, before COVID transformed the landscape, that fear has escaped the texts and burrowed into the minds of teachers and young people alike.

Depending on the exam board, teachers may have not recently taught either poetry, the modern text or the 19th century novel. For their part, students may have learning gaps, or be less resilient readers, having experienced learning in lockdown during Y8 and Y9.

This year, both literature papers are to be sat a week apart in May. An Ofqual statement made in September 2022, announcing the return of pre-pandemic grading, has additionally sent shivers down the spines of teachers and leaders (though students will be ‘protected’, if grades are lower than normal, by senior examiners acting on prior attainment data and grades achieved by previous cohorts).

Our task is to therefore try and eradicate those pre-exam fears plaguing our students, our colleagues and ourselves – but how should we do that?

Little wins

If a certain type of exam response has become a threatening behemoth, break it down. Learn a set of quotations in class around a specific theme or character, perhaps with the aid of mini whiteboards, pair talk, timed conditions and/or buckets of praise.

A set of short quotations firmly lodged in students’ heads equals a win, and with every win we feel more successful, more empowered and less afraid.

We practise a similar approach when it comes to verbs that explain effect (‘emphasises’, ‘highlights’, ‘reinforces’, ‘creates’ etc.) and phrases relating to social and historical context. We can do it with adjectives that describe character, or indeed many aspects of the complex responses our students will be required to give in the exam.

Active revision modelling

Beware those pretty notebooks and flashcards that haven’t yet become grubby through continual handling and flipping. It’s worth reflecting on how many of our students see their studies and exam preparation as a solitary, inactive and ultimately passive activity.

I myself now know that the hours I spent studying for both GCSE and A Level exams could have been utilised so much more productively had I known just how ineffective my 1am note copying sessions really were.

As Pie Corbett – the brilliant teacher, trainer and poet behind Talk For Writing – says,‘If you can’t say it, you can’t write it’. That’s certainly something I need to consider more in my own practice.

Emphasise to your students that their beautifully neat notes are next to useless unless they’re also kept securely in their heads.

Immersion and joy

All of us will have different opinions on the texts we teach, the selections we’ve made and the factors governing those choices.

We need to recognise that at some point, we have to acknowledge the value and worth offered by even our most loathed set texts. Select the best chapter, best act or best online poetry reading of the texts in question, and then just read and/or listen to them – potentially for the duration of a whole lesson.

Invite your students to identify their own favourite lines, or pick out a work’s most humorous moments or haunting sentences. Try to recapture that moment when your fresh- faced Y10 students were first presented with a text’s then-new words, long before assessments, mocks and feedback began to eat away at its appeal. Relax, immerse and do your best to help everyone enjoy those well-written texts as if PETER paragraphs had never been invented.

Pair writing

How can we turn the demands of assessment objectives on responses inside out? One way is to outline what these actually are, and ask students to co-write a single response. Two brains, one paragraph/essay.

By doing this, we’re not only facilitating the exposure of different writing styles and different interpretations, but also different sets of notes.

Needless to say, this is an activity in which students will need be matched carefully, and for which ground rules will need to be laid down. Both students must physically contribute to the actual writing. Both sets of notes/resources will need to be accessible, and both should actually understand what it is they’re writing.

Once the activity is complete, invite your students to look back over their responses and take the best phrases and ideas from both. Yes, it can take practice and monitoring to get this right, but even the inevitable minor disagreements between partners will help to develop their knowledge and expression.

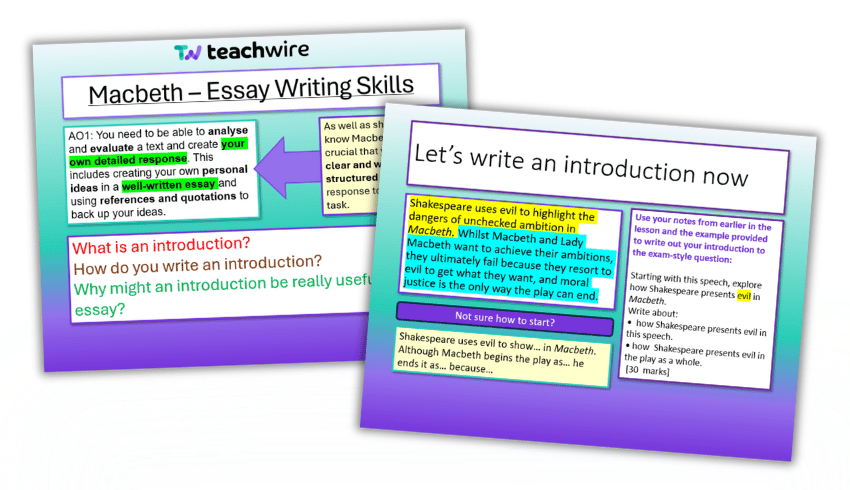

Macbeth essay writing resource

This free, detailed Macbeth essay two-lesson resource pack contains two comprehensive PowerPoints which will support KS4 students in constructing coherent and clear essay structures for an exam-style question.

Tentative language

‘Could’, ‘maybe’, ‘possibly’, ‘perhaps’; such tentative language (often heavily demanded at undergraduate and Master’s level) can give nervous students a renewed sense of confidence, especially when faced with previously unseen texts.

Model sentences that contain these words. Encourage their use in verbal responses during class discussion. Explain how they’re frequently employed in academic writing, and emphasise how they can raise the intellectual bar of our writing while also, fabulously, giving us an insurance policy if we’re perhaps a little bit off….

Comprehension and the basics

As evidence mounts that students’ comprehension skills often aren’t as developed as we think, it’s worth checking to see if they really get it – especially when it comes to unseen poetry.

How often have you watched students spot a simile prior to reading the whole poem? Most of us will also have seen the detrimental effects of not truly understanding a text when devising language responses. I sometimes wonder if we’ve successfully trained students in identifying language to the detriment of comprehending texts in their entirety, and what they’re actually about.

Equally, when it comes to other studied texts – notably Shakespeare – do students know what’s happening in any given scene and that scene’s purpose? Sequencing and summarising exercises, quizzes, and ‘true or false’ questioning will help reveal misunderstanding.

I hate the phrase, ‘We’ve got this’, but in this case, I really think we do, and that our students should be told. Perhaps not in the booming personal trainer voice those words evoke in my head, but in myriad little ways; in every lesson, with every small win, and alongside every positive change in habit and chunk of confidence gained.

It’s not like we haven’t made the hitherto unfamiliar known, and therefore not threatening to our students before – remote live earning, TAGS, the list goes on. We don’t need to be afraid.

Making revision effective

- Take time in lessons to demonstrate self-testing (even the old ‘look, say, cover, write, check’).

- Show students how to map a theme or character via colourful mind-maps, or by using images accompanied by text.

- Remind students that they can use their omnipresent phones to record verbal notes after watching online revision videos, or themselves talking through an essay before writing it.

- Encourage students to test each other, or have a family member step in. It doesn’t matter if nan doesn’t know the novel – give her a list of points on paper, and ask her to make sure you’ve said them all.

Jennifer Hampton (@brightonteacher) is an English teacher, literacy lead and former SLE (literacy). Browse great ideas to help with GCSE English Language revision.