Boost Literacy Learning with the Power of Picturebooks

Picturebooks are often perceived as a step into reading for our youngest children, but exploring them with KS1/2 pupils can lead to some powerful literacy learning, says Charlotte Hacking…

Whom do Year 5 children think picturebooks are for and why do they believe we have them on our shelves?

Some know that they are “for anyone, young or old – because it gives us all a message”, but others have the impression that “picturebooks are for people that can’t really read. That’s why the pictures are there, to give them an idea of what the book is about”.

What can we do to make sure children read a range and breadth of texts, including picturebooks, graphic novels and film? How can we support teachers to show that this reading has a positive impact on the progress and outcomes for pupils?

When national organisations only show examples of Y6 children reaching age-related expectations through reading short stories and novels, this becomes even more important.

Why are picturebooks so important?

For the last six years at the CLPE, we have been conducting a research project into the use of picturebooks throughout the primary years.

We have collected concrete evidence that shows that teaching children how an author/illustrator conveys meaning through words and pictures supports the development of visual and critical literacy skills.

Our research shows that children need time and opportunities to enjoy and respond to the pictures and to talk together about what the illustrations contribute to their understanding of the text. But what should we look for when reading? Here are just a few things to begin to investigate…

Facial expressions and body position

Sometimes this can be marked and obvious, as in the representation of the cats’ initial suspicion and fear of the dog in Viviane Schwarz’s Is There a Dog in this Book?.

These cats, whose expressions turn from love to loss and back to love are drawn with dramatic, very physical reactions which children can easily relate to.

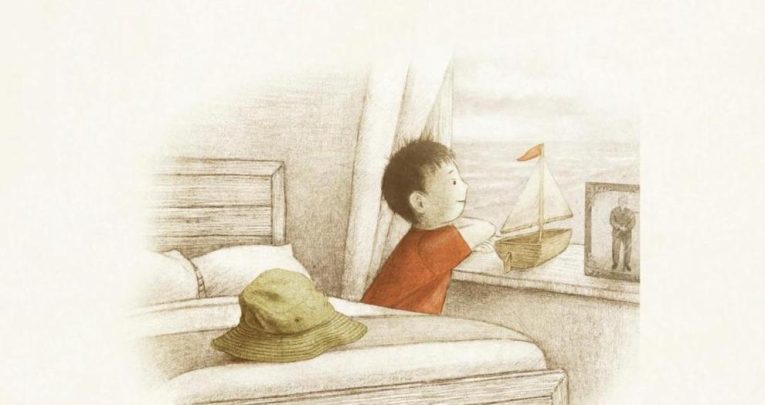

In some texts, such as Benji Davies’ The Storm Whale, this is more subtle; the tilt of a head, the twist of a foot or the removal of the mouth can say huge amount about the personality, emotions or reactions of a character.

Props and visual links

The props that an illustrator draws with their characters increases the reader’s understanding about them.

In Grandad’s Island by Benji Davies, Grandad is dressed in a smart buttoned up shirt, tie and sleeveless jumper on his top half, with pyjama bottoms on the bottom.

What might this suggest about his character?

In the first half of the text, we learn most about the character not through the words on the page, but through the objects and items in his home.

He carries a walking stick at the start of the story but discards this in the middle of the text as he finds a new freedom on the island he journeys to with his grandson.

Colour

Colour palettes can be specifically chosen for texts. For example, Chris Haughton’s books are all defined by their distinct choice of colour from the vibrant orange, red and pink of Oh No, George! to the contrast between the cool blues and vibrant greens, pinks and yellows in Ssh! We Have a Plan.

At other times colours can be used to symbolise, signify a change of mood or period in time, as is beautifully evidenced in the Fan brothers’ Ocean Meets Sky where sepia tones are used to represent memories and the text moves into richer colourful spreads when the main character journeys into a fantasy world of his imagination.

The journey

Lines on the page and directionality of characters can tell us a great deal about how a story progresses or the emotional turns a story may take.

One of the most famous examples of this is in Maurice Sendak’s Where The Wild Things Are. From the point where Max gets sent to his room, his body faces forward, leading us on to turn the page.

He turns back to face the sea creature as he arrives at the place ‘where the wild things are’, but the boat lurches forward as if to throw him forwards into continuing the journey and the bowsprit of the boat points him forward at each step of the way.

In the last scenes of the rumpus, his body turns back, signalling the steps to his return home.

Framing, layout and separation

In texts such as Croc and Bird by Alexis Deacon, pages and spreads are used in different ways for different effects on the reader.

The use of frames signals the passing of time and sequential series of steps, vignettes are used to focus on characters and their relationship, without background elements distracting.

Spreads where there are pictures but no words force us as the reader to make meaning from what we see, those that have words but no pictures force us to visualise and empathise.

Discussions about illustrations include all children and help to make a written text more accessible. Time spent focusing on illustration contributes to children’s ability to read for meaning, express their ideas and respond to the texts they encounter.

Everybody in the class brings their own ideas and prior knowledge to the discussion and this is an important and engaging way of developing critical thinking, vocabulary and the ability to think from different points of view.

Studying pictures in detail helps us to build powerful readers.

Find out more about the Power of Pictures project, including videos of authors working, research summary and free teaching sequences so you can use picture books in Early Years, Key Stage 1 and Key Stage 2 at clpe.org.uk/powerofpictures.

5 to share with older readers…

Croc and Bird by Alexis Deacon (Red Fox)

Older readers may discuss themes of nature and nurture, what it means to be a family, being alone, growing and changing and having to make choices, and how an illustrator uses layout and colour as part of the storytelling.

Grandad’s Island by Benji Davies (Simon and Schuster)

Older children may pick up on themes of dementia, bereavement, and talk about how an illustrator uses colour, props and visual links as part of the storytelling.

Is There A Dog In This Book? By Viviane Schwarz (Walker)

Older readers will engage with the graphic style of the text and be able to discuss how illustrators convey emotion through facial expression and body position. They will also be able to challenge perceptions of characters based on appearance.

Wild by Emily Hughes (Flying Eye)

Older children may discuss themes of nature and nurture, freedom and responsibility, the rights of children and human impact on the environment, and will be able to investigate how an illustrator uses colour, facial expression, body position and page layout as part of the storytelling.

How To Be a Lion by Ed Vere (Penguin Random House)

Older readers could make links with current day concerns such as toxic masculinity and community cohesion, and investigate how simple shapes, lines and backgrounds can be powerful in focusing our attentions on characters and their story

Charlotte Hacking is the Learning Programmes Leader at the Centre for Literacy in Primary Education (CLPE). Along with author illustrator Ed Vere, she devised CLPE’s new project The Power of Pictures, designed to explore how a focus on picturebooks throughout the primary years can develop children’s inference, deduction and reader response as well as teaching them about the craft of writing in words and pictures.