Combine Mathematical Problem Solving With Real-World Scientific Contexts With These Activities

Maths + Science = ?, Alan Cross and Alison Borthwick lead the investigation

It’s hard to detect many differences between the abilities required in learning science and those of learning mathematics. Both subjects are about perceiving what is going on in the world, establishing relationships, making things predictable and using this to either expand knowledge and understanding or in other ways improve life.

Science provides the ideal context to harness the skills learnt through mathematical problem solving, but in a real-life setting – and combing the two subjects creates more opportunities to practice the skills needed to be successful at both. Mathematics, for its part, provides science with a means of describing, quantifying and articulating ideas and relationships.

We are not advocating that every mathematics or science lesson adopt full integration, however, we will show through these activities that there are many opportunities where connecting the subjects is natural, adds value to the learning and makes sense.

1 Rapunzel’s garden

This activity challenges learners to plan and make a garden for Rapunzel. However, Rapunzel has certain criteria that must be followed. Her garden needs to include:

• Colour • Plants to eat • Grass • A surprise

The mathematics part of this challenge is to use knowledge of fractions to ensure the whole garden is used and the proportions all total one (garden). The science aspect of this activity is to learn more about plants and flowers, including some of their names and how they grow.

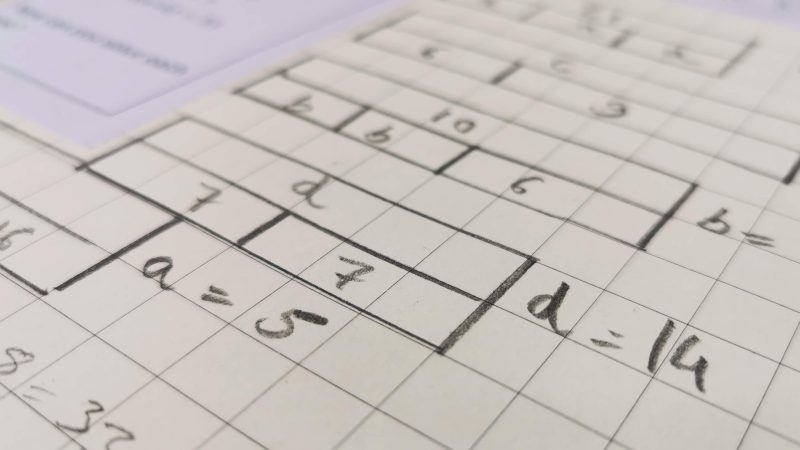

Ask learners to plan their garden on paper first before planting it out in containers. They must decide how much of the garden to give each section. For example, they may decide to divide their garden into tenths or thirds. However, you could also encourage a mixture of fractions. Learners in one Year 2 class decided to divide their garden into eighths and quarters and were very successful in planning their plants, flowers and grass.

Discuss with learners what makes a garden colourful. Explore different flowers and their names. Which flowers do they prefer? Rapunzel also needs to grow plants she can eat. Make a list of plants they could include, such as carrots, lettuce, cress, onions, parsley or basil. The surprise section is for them to use their creative skills. To support learners in deciding which flowers and plants to include, try, where possible, to have real-life examples. This also provides opportunities to use hand lenses to observe flowers and plants in detail, which combines important ‘working scientifically’ skills. Encourage children to compare and contrast the different plants and flowers.

Once learners have planned their gardens on paper, they can plant them out in containers or in a patch of the school grounds. This allows the activity to be extended over several weeks, as learners need to discover what their seeds and bulbs require in order to grow.

2 Centipede’s shoes

Mathematics-led activity This activity is based on the story Centipede’s 100 Shoes (Ross, 2003). Begin by discussing different types of invertebrates that learners know about and ask them how many legs they think the animals have. Record this information, but do not reveal the answers yet, as this is the science activity coming up.

In the story, the centipede hurts his toe and so decides to buy some shoes. He buys one hundred shoes as he thinks he has this many feet. As a class, decide how many legs your centipede will have.

Let’s choose 58. Set learners a number of challenges based on this centipede. For example: 1. If the centipede has 58 feet, how many pairs of shoes do we need? 2. How many shoes and socks is that altogether? 3. If we bought 100 pairs of shoes, how many would we have left over?

These questions allow learners to use their reasoning skills to convince each other about the number of shoes needed but also use their fluency skills to see relationships between numbers. For each question, ask learners to think how they will record their information, provide a reason for their approach and solution, and ultimately solve the problem, all of which support them in working mathematically.

Science-led activity Do all invertebrates have the same number of legs? Return to the information children provided on how many legs they think each of the invertebrates has, and research how many legs each creature actually does have. You could do this using live invertebrates (ensuring the pupils treat them carefully), picture books or the internet.

Once learners are armed with this information, take them outside to become explorers. Ask them to look for invertebrates. They may start by observing signs of plants being eaten, or habitats in which invertebrates live. If they find an invertebrate, take a photo of it. Back in the classroom, discuss where learners found them. What does this tell us about the habitats they choose?

3 The king has lost his crown!

King Arnold has lost his crown, and he’s asked the class to design and make a new one, but there are several rules they need to follow:

1. The crown must have a circumference of 62 centimetres. 2. It must be made of at least three different materials. 3. It must include different-shaped jewels which need to be organised in a symmetrical pattern. 4. It must be waterproof. 5. Each child will be given £5 with which to buy the jewels. 6. Five smaller jewels can be exchanged for one larger jewel. 7. The crown must be suitable to wear all year round.

Each rule draws on aspects of working scientifically and mathematically. For example, ensuring the crown must be waterproof will require learners to gather data about different materials, while using different-shaped jewels utilises understanding of pattern within problem-solving skills.

4 Snail trail

Introduce your class to live snails, stressing the need for personal hygiene once handled and care towards the creatures, particularly the need to pick them up very gently by the shell and that the body and eyes are very delicate. Can the children describe the shell and skin? Can they estimate length, width and mass? Measuring snail length can be difficult, as they rarely stay still. With care and a magnifying glass can they observe the snail’s mouth?

In order to observe the snail’s foot operating, place the snail carefully on transparent plastic and slowly turn it upside down – children can then see the waves of muscular action on the foot that propel the snail. Place this sheet on squared paper to measure the snail’s length and distance travelled in 30 seconds or one minute.

Once learners have measured distance travelled in 30 seconds or one minute, ask them to calculate the distances travelled over five minutes, 10 minutes, an hour, a day, etc. Consider the need for repeat readings. Ask learners to measure the distance travelled by three snails so that they can calculate the mean, mode and median. Can they look at a local map and its scale to see where the snail might reach if it travelled in a straight line?

These activities were taken from Connecting Primary Maths & Science by Alan Cross and Alison Borthwick, published by McGraw Hill Education

Dr Alan Cross is a senior teaching fellow at the University of Manchester.

Alison Borthwick is a mathematics advisor for Norfolk Local Authority, UK, and chair of the primary group for the Association of Teachers of Maths and the Mathematical Association.