7 surprising things we know about maths

Poking around in education research can throw up some unexpected discoveries – and take your teaching in new directions – says Lucy Rycroft-Smith…

Picture this: one minute you’re a maths teacher, the next you get offered the chance to get paid to read maths education research and write about it for other teachers.

Dream or nightmare?

Privilege or responsibility?

Would you do it?

Of course there’s more to this story (and it didn’t happen quite so instantaneously!). But for me, my job in Communication and Research at Cambridge Maths takes me to as many mental happy places as it does international conferences.

I’m over the moon to be so immersed in the world of maths education research, but always make sure I have an eye on translating it for teachers and thinking about the central idea of a dialogue (and sometimes fuzzy identity boundaries) between teacher and researcher.

You can read some of our Espressos at cambridgemaths.org/espresso – we take a question in maths education (usually across sectors and age groups) and write about the research, classroom implications, and key ideas, including a specially-designed infographic and hyperlinks to original sources.

You may have noticed the ‘we’ there – I have the joy of working with a team of experts here at Cambridge Maths, as well as getting to collaborate with a veritable smorgasbord of maths education celebrities in the UK and beyond.

So how can reading about maths education research help you? That’s for you to decide, of course.

But one of the benefits I’d suggest is the ‘knowledge is power’ (France is bacon) argument – while research can’t (and shouldn’t) tell you what to do, it can empower teachers to take charge of their own professional development, give an impetus for experiment and innovation, and provide rationale for pushback against dodgy policies.

Here are a few of the most interesting and useful things I’ve found from maths education research over the course of writing Espressos:

1 | The gender trap

Males tend to overestimate their own mathematical abilities; females to underestimate them. This is from a study done by Hassmen et al (2002) on adults, although there has been some replication, some with children.

This seems to resonate with teachers, who tell me this is what they find in their own classrooms.

2 | Hard times

Pupils are least accurate at the 12 and 8 times tables; then 7, 6, 9, 4, 11, 3, 5, 10 and finally 2 and 1.

This was a large study (232 children in KS2) but not in a scientific journal (collaboration between the Guardian and tech company in 2013).

The zero times table was not included, which is a shame in my opinion – and I don’t know of a similar study among adults – please send me one if you see it!

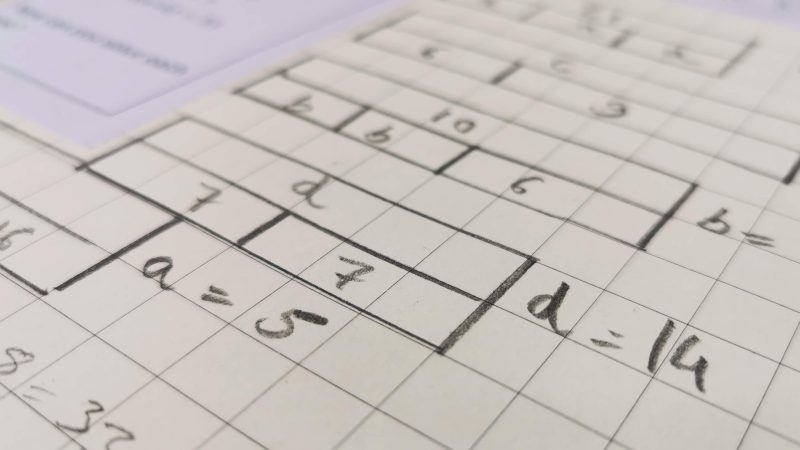

3 | Defining features

When asked to weight these definitions of mathematics (the question was “Give each statement a percentage, so that the sum of the three percentages in each section is 100’’) maths teachers came up with the following (% are mean weightings):

- A given body of knowledge and standard procedures; a set of universal truths and rules which need to be conveyed to students 45.2%

- A creative subject in which the teacher should take a facilitating role, allowing students to create their own concepts and methods 29.3%

- An interconnected body of ideas which the teacher and the student create together through discussion 25.5%

This is from a Swan (2002) paper about teacher beliefs and I particularly like the weighting idea, as it gives room for overlapping definitions; however, this was a small study of only 64 FE maths teachers. How would you answer?

4 | Four is more

One-year-old infants can consistently distinguish between (and choose the larger of) two and three objects, but not two and four objects.

This is from a paper by Feigenson, & Carey (2003), and highlights the interesting way our brains are quite good at ‘seeing’ one to three objects almost from birth, but find that four seem to blend into a more general conception of ‘more’ until we learn to count.

5 | Quality counts

In a meta-analysis of studies (not confined to maths), Schacter & Thum, (2004) looked at three things that might represent teacher ‘quality’ and found:

- Teacher education beyond first degree: 8% of studies showed positive correlation

- Teacher years of experience: 29% of studies showed positive correlation

- Teacher test scores (eg subject knowledge, verbal ability, teaching knowledge tests etc): 42% of studies showed positive correlation

Does that surprise you?

6 | New order

There’s a type of research-based mathematics curriculum where algebra is introduced earlier than number (see Dougherty & Simon, 2014). It was developed in Russia in the 1960s by a researcher called Davydov and is still being widely discussed today.

7 | Title sequences…

Maths education research paper titles (and I’ve read quite a few) can be a source of great joy, amusement, or even the odd pun.

A small selection of my favourites: for pure poetry, I like ‘Tornado-shaped curves’ (Martinez et al) and Cumber’s ‘Waggling conical pendulums and visualization in mechanics’, as well as Wares’ ‘Looking for Pythagoras between the folds’; titles that made me smile included ‘Algorithms Alcatraz: Are children prisoners of process?’ (Huntley & Hurst), ‘Flip or flop? Students’ perspectives of a flipped lecture in mathematics’ (Novak et al); and I very much enjoy a pun title, such as ‘It’s about time: the relationships between coverage and instructional practices in college calculus’ (Johnson et al).

Finally, some of the most intriguing ones (that I simply had to read, even if they weren’t relevant to my work at the time) include: ‘Loving and Loathing: Portrayals of School Mathematics in Young Adult Fiction (Darragh), Schukajlow & Achmetli’s ‘Multiple solutions for real-world problems and students’ enjoyment, and boredom’ (it’s the slight pause before the final two words that I particularly loved here) and, perhaps most intriguing of all: ‘Zombies: a simple discrete model of the apocalypse’(Abernethy).

If that doesn’t get you Googling, I’m not sure what will.

As always, reading and using education research comes with several caveats: nothing is guaranteed to work; teacher knowledge and expertise is valuable and important too; and theories are just that – theories – until we test them, improve upon them, and refine them by considering their interactions with the real world of the classroom.

Please feel free to send me your interesting finds from maths education research at @CambridgeMaths or lucy.rycroft-smith@cambridgemaths.org.

Lucy Rycroft-Smith works in Research and Communications at Cambridge Mathematics, a Cambridge University organisation designing a digital, research-based Framework for mathematics education.