Use local history to give students a sense of identity

Uncovering the stories that shape where they live can help young people develop powerful historical skills and a strong sense of identity, says Gemma Hargraves…

Identity is a funny thing. Both a modern concept and deeply rooted in history, it can be complex to unfold – and never more so than for young people trying to understand who they are, or with which community they most identify.

Local history may hold the key to unlocking these issues; which is just one good reason why it should be included on the KS3 curriculum, and beyond.

Not only to capitalise on the good work done by primary schools, and to prepare pupils for a historic environment study at GCSE, but because local history also has clear academic value.

It can provide a depth study in a way that would be impossible with a national topic, utilising and developing pupils’ source skills and knowledge, as well as offering clear benefits in terms of nurturing empathy and identity.

Themed focuses such as LGBT History Month or Black History Month activities are great to raise awareness and representativeness in schools’ history curricula, but studying local narratives can take us further (see outstoriesbristol.org.uk as an example of LGBT history research at a local level).

Setting out

It can be difficult to know where to start, though, especially if neither teacher nor pupils live in the locality. The best way to begin, is by observing your surroundings and orientating yourself.

Take in your school demographic, finding out what interests the community, or has the potential to do so.

Orientate yourself locally and nationally – if you are not yet aware of local history, kick off your research with the suggested websites in the ‘useful sources’ panel on these pages, or local archives.

By initially linking your study to the pupil demographic and their interests you will anchor it in their own identity, be that migratory or Anglo-Saxon.

This is also a key time to enlist the support of your geography department, who may have helpful migration resources, and access to online mapping software through which you can investigate the changing landscape over time.

Consider Historic England’s Heritage Schools initiative for more structured support.

Additionally, war memorials can be a superb starting point – there are more than 100,000 in the UK, with most communities having at least one.

However, they often go unnoticed, so War Memorials Trust can be useful to locate your local memorial (and even contribute to its conservation). Aerial and vintage photographs are also invaluable as you embark on any study.

A closer look

After observing and orientating, the planning can commence. It is important to start with an overarching question, then be prepared to narrow down to people and focus points such as buildings or roads.

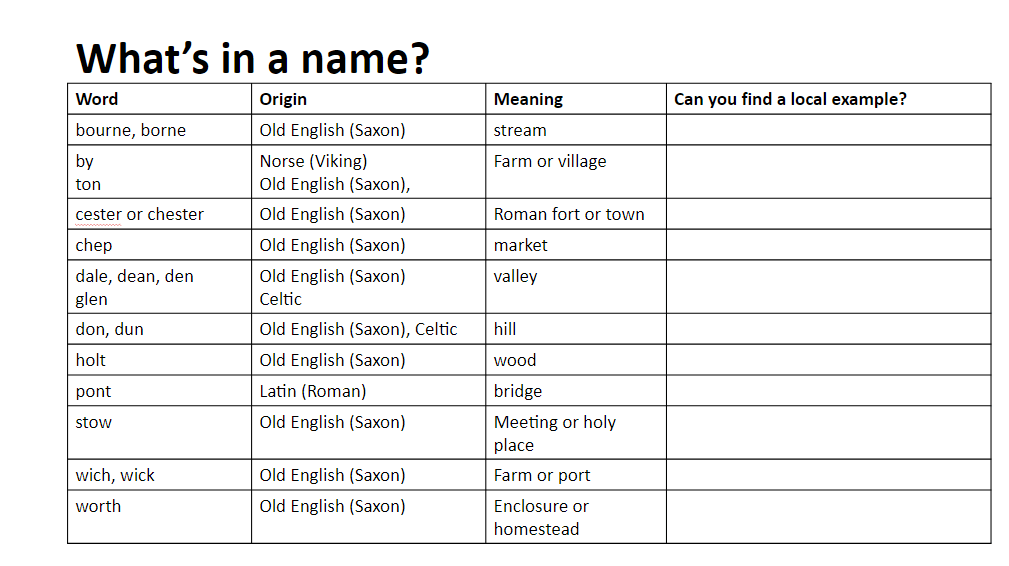

Street, suburb and even pub names can offer fascinating historical insights (see the linked resource available here).

Consider why some streets or buildings may have been neglected by traditional local history narratives and you could uncover some hidden gems of knowledge; equally, your local history study may fit neatly in to existing KS3 topics such as British Empire, Victorians or Suffragettes.

Utilising the websites already mentioned, pupils could complete a data analysis task for homework, with the additional benefit of numeracy and cross-curricular links.

For a social focus, consider the National Archives Census database from 1841-1911, which could be perfect for any Victorians topic, or as background for the famous 1911 Suffragette census boycott.

Trade directories were also published from the Victorian era onwards and provide detailed evidence about particular areas. These also often have advertisements on the back, providing an intriguing glimpse of everyday life at the time.

Old newspapers are of course valuable, and many are now digitised.

In terms of differentiation, there is an opportunity to consider oral history if your school is located in a community where families have lived in the area for generations.

Cemeteries are also a fantastic resource. And do not be afraid to enlist the help of your local history society – one of its members may already be conducting research around your question.

Local museums may be a wonderful source of artefacts, and some even offer ‘takeaway’ boxes to bring your local history in to the classroom.

Diverse perspectives

Local history can also be international and more diverse than you may imagine; consider the London Olympics as a study in twentieth century change and continuity (1908, 1948 and 2012), or the Commonwealth Games in London (1934), Cardiff (1958), Edinburgh (1970, 1986) Manchester (2002), or Glasgow (2014) to explore local economic history in the context of the Empire.

This could be extended to consider the Paralympics (Stoke Mandeville 1984), or Special Olympics GB (Liverpool 1978, 2021) and Leicester (1989, 2009), again offering interesting opportunities to study change and continuity both socially and economically.

Surely it is clear that there is an opportunity here to develop pupils’ sense of identity, and an engagement with ‘British Values’.

Local archives and museums can be utilised to ‘do history’ in a real way rather than relying on textbooks, with the added benefit of building skills for those facing the historic environment study at GCSE.

For a medieval or early modern focus, the GCSE historic environment studies currently focus on Restoration England or earlier, and pleasingly, following publication of Miranda Kaufmann’s Black Tudors book, many archives are now prepared for requests about BAME people in the past.

For a more recent focus on BAME history, the ‘Windrush Strikes Back’ project aims to ‘research the presence and perspective of African Caribbean people and their entangled histories’ throughout the Midlands.

The theme of race here could also be useful background for those studying an American history course at GCSE or A Level.

Thus, a local history study can help build empathy and respect, as well as shedding light on traditionally neglected histories – with the potential added benefit of developing conceptual awareness ahead of examined courses.

Real rewards

The challenge is to make a local history study meaningful and responsive, rather than token or prescriptive. Be flexible, establish bite-sized targets, and do not be afraid to be academically rigorous.

Prepare for setbacks, and treat them as a lesson in resilience as pupils overcome them. Hopefully it is now clear that local history need not be a discrete topic, but could instead add depth and a local element to an existing scheme of work, or serve as preparatory work for examination classes.

And there are ways for your students’ work to be recognised and rewarded, too; history teachers will no doubt already be aware of the Young Historian Project and the awards they offer for individual work at KS3 and GCSE on any local history theme.

With all these benefits on offer, then, the argument in favour of considering a local element in your history curriculum is a pretty compelling one; and, with May being Local and Community History Month, now is the perfect time to get planning!

7 useful sources for local historians

- Census Records

- Find your local archives

- Heritage Schools

- LGBT+ – Bristol

- Special Olympics

- War Memorials Trust

- Windrush Strikes Back

Gemma Hargraves teaches History at a girls’ school in the Midlands and is currently embarking on her own archival study of local politics in mid-18th-century Gloucestershire.