Primary Book Topic – How AF Harrold’s ‘The Imaginary’ Explores Imagination, Memory And Loss

Losing a companion, even a make-believe one, can be hard. Show children how the power of imagination can let them express their feelings, fears and sense of self, says Sue Cowley…

- by Sue Cowley

The Imaginary tells the story of Amanda and her imaginary friend Rudger. Things start to go wrong for them when the evil Mr Bunting and his imaginary accomplice find them. Mr Bunting needs to feast on imaginaries to keep himself alive, and he plans to eat Rudger if he can possibly catch him…

When Amanda is knocked down by a car, and whisked off to hospital unconscious, Rudger finds himself fading. Luckily, a cat called Zinzan helps him find his way to The Agency – the library where imaginary characters can wait for a child to bring them into being. But Rudger doesn’t belong to just any old child; he wants to find his way back to Amanda.

After a series of adventures, Amanda and Rudger are finally reunited and, with the help of Amanda’s mum, they manage to destroy Mr Bunting. Rudger knows that Amanda won’t imagine him forever, but he knows that he will live on in her memory when he has gone. The Imaginary deals with complex themes around imagination, memory and loss, through a gripping and fast-paced story that will keep your children enthralled. Emily Gravett’s powerful and disturbing illustrations offer the perfect companion to AF Harrold’s story.

Introducing the story

The book starts with ‘Remember’ by Christina Rossetti – a poem about loss and memory. Share this poem with your children and encourage them to draw out some of its meaning. What do the children think Rossetti means by ‘the silent land’? Why would Rossetti say that it is better to ‘forget and smile’ than to ‘remember and be sad’?

Now read the introduction of the book to the class. Who do the children think Rudger is, and why is he slipping away? What could the ‘Imaginary’ of the title be?

Amanda

Amanda is a complex character. Even though the story appears to be told from Rudger’s perspective, it’s she who is the central character and the most fully developed. Reread the description of Amanda dealing with her knotted laces (p5-8).

• What can you tell about Amanda from the way she behaves here, and the actions she takes to deal with her laces? • “She, Amanda Shuffleup, was a genius. That much was clear.” What does it make you think about Amanda when you hear her thoughts about herself? • Why do you think Amanda denies treading mud into the carpet? What might this say about her as a character?

Look at the way Amanda treats Rudger after Mr Bunting tries to snatch him during the game of hide and seek. Reread the section from p55-62. What do the children think about how Amanda is portrayed here? Why do they think Amanda treats Rudger in this way?

Dens and destinations

Amanda and Rudger enjoy playing in the den at the end of the garden, pretending it is all kinds of different places.

Reread the description of them playing in the den, on p17-18. Ask the children to imagine they are playing in a den with a real or imaginary friend. What different places would they pretend to go to, and what kind of things would they imagine themselves doing with their friend?

Get the children to write a short descriptive piece, using the phrases ‘One day the den would be…’ and ‘Another day the den would be…’.

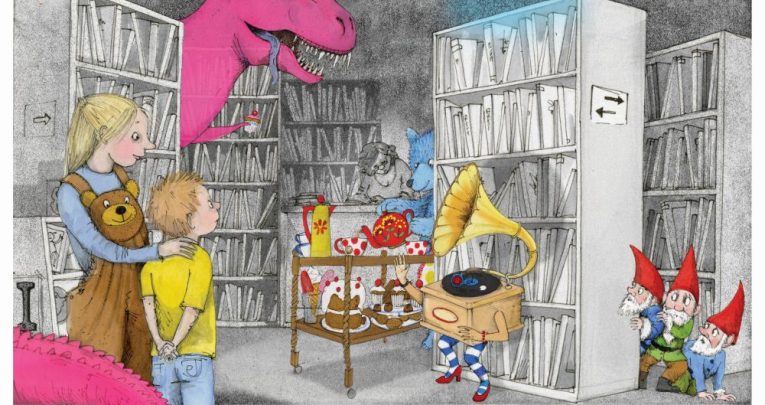

Illustrations and dramatic tension

Emily Gravett’s illustrations add strongly to the sense of fear and dramatic tension in the book. Talk together about the illustrations that are used during the description of Amanda’s game of hide and seek, when the storm causes a power cut (p37-50).

• What is the effect on the reader of the white writing on black pages? • How do the flashes of lightning work to intensify the tension? • Which sentences and phrases add to the sense of drama? • How does the image of the girl’s legs on p42-43 add to the tension? • What is the effect of short sentences, such as “And then the lights went out.”?

Mr Bunting

Look at the description of Mr Bunting, and the picture of his open mouth as he tries to swallow Rudger (p67-69), and read the part when he swallows Emily (p120-122). Talk with your children about the similes, and the images they create in the reader’s mind:

• “unhinged it almost, snake-like” • “smelt like a desert might smell, dry and reddish and rotten with spice” • “like a white-tiled tunnel running off into the far distance” • “stuck, like an insect in amber” • “pulled out like dribbling custard”

Create your own similes, taking the idea of an open mouth as a starting point. Brainstorm words using each of the senses – what might an open mouth smell, taste, feel, look and sound like? What is their open mouth doing and how can similes add to the overall effect? Reread the section in the library where the characters tell the story of Mr Bunting, from the bottom of page 100 to page 103. Why do the characters in the library believe that the story of Mr Bunting is made up? Look at chapter eight (p126) where Cruncher-of-Bones says that Mr Bunting is an urban myth.

What is an ‘urban myth’ and why do these stories develop?

Zinzan the Cat

Although Zinzan only has a small part in the story, the character of the cat is vividly portrayed and he plays a pivotal role in Rudger’s escape from Mr Bunting. Read the description of Rudger on pages 81-82, talking about how the imagery quickly creates a clear picture of the cat’s character.

• Why does Rudger assume he is dealing with a “cat of refinement”, before he sees Zinzan? • Why does Zinzan look so different to how he sounds in Rudger’s imagination? What might have happened to him? • Zinzan is described as “like a cat put together from the leftover parts of several other cats who’d been in a war, all on the losing side.” What kind of images does this simile create in the children’s minds? • What does Zinzan mean when he says that Rudger might be “the answer to a question she got no other answer to.”? What might Amanda’s question have been?

Get the children to draw their own ‘Good Samaritan’ cats that have been through the wars. Ask them to write a description of their cat, using similes to give a strong image.

Imagination and the library

In many ways, this book is a celebration of libraries – a place where imagination lives on inside the covers of books.

• “It’s the best sort of indoors there is for a rainy day. Every book is an adventure.” (p87) • “Look around, this place is like an oasis: it’s made of imagination.” (p94) • “That’s what the reals are for, dreaming stuff up.” (p99)

Talk with your children about their experiences of libraries. What kind of libraries have they visited? What do they like to do when they are in a library? What storybook characters would they most like to bring to life? Ask the children to write a scene in a library, where some of the characters from stories come to life, brainstorming interesting combinations of characters.

Belief and the imagination

The parents in the story, and the children that Rudger meets, all react very differently to imaginary friends. John Jenkins and his family are terrified, believing that he has seen a ghost. Julia is mean to Rudger, while her mother, Mrs Radiche, thinks her daughter is hallucinating and takes her to a child psychologist. But Amanda’s mum seems perfectly comfortable with the idea of Rudger; she had her own imaginary friend when she was young.

• Why do the children think that the different people react differently to imaginary friends? • What emotions cause the children and their parents to behave in this way in the story? • Is it possible to believe in something that you can’t see, even when you are grown up? • Why do people tend to become less imaginative as they get older? • Why do they think Mrs Shuffleup is finally able to see the imaginary beings, when Amanda is in danger in the hospital?

Memory and loss

One of the key themes in the book is that of memory and loss. In chapter two Amanda’s mum has a fleeting memory of Fridge, her imaginary friend when she was young. On p74 we find out that there is a photograph of Amanda’s dad on the hallway wall, but that he died before she was born. Could it be that Amanda’s loss is linked to her need for an imaginary friend? Reread p208-209, where Mr Bunting accidentally swallows his imaginary friend. Mr Bunting says that “Everything he cared for, everyone he cared for, everything he’d known was all long gone”. How do the children feel about Mr Bunting at this point in the story? Does he still seem as evil as he did at the start? At the end of the story, Rudger muses on memory and loss: “Imagination is slippery, Rudger knew that well enough. Memory doesn’t hold it tight, it has trouble enough holding on to the real, remembering the real people who are lost. He was pleased she had the photo, that she’d made the photo, that she had something of him that wouldn’t fade, because one day, he knew, as unlikely as it seemed, she would forget him. It was what happened in time, no one’s fault, just the way things go.” Talk with your children about how this section links with the Emily Dickinson poem that they heard at the start of the book. There are some complex philosophical and religious questions that you could draw out here, particularly with older students, although you would obviously need to be sensitive to your children’s personal experiences. Is someone really gone, if we still have memories of them? How do we go about remembering the people who are no longer with us? Is there anything left of us when we die, that goes beyond a memory or a photograph?

Design your own imaginary friend

Rudger’s appearance changes according to who is imagining him. When he is temporarily in Julia’s imagination, and much to Rudger’s disgust, she sees him as a girl with ringlets of red hair, wearing a dress. In chapter six we see descriptions of all different kinds of imaginary characters, including Lizzie Shuffleup’s old imaginary friend Fridge, the dog. Many of the friends are drawn from what seem to be fictionalised characters, such as Snowflake, the pink Tyrannosaurus Rex. What story characters would the children love to ‘meet’ in real life? Get your children to make up their own imaginary friends. They could:

• Write a description of their friend, using figurative and descriptive language. • Create a character profile of their imaginary friend, in a ‘Top Trumps’ style. • Make imaginary friend puppets, and use them to tell a story. • Create a whole-class collage of a scene in a library, where the imaginary friends meet.

A set of teachers’ notes on The Imaginary can be downloaded as a PDF from the book’s publisher, Bloomsbury

Sue Cowley is a teacher, author and presenter. Her latest book, The Artful Educator, is due to be published by Crown House in early 2017