Engage Parents In Maths By Showing Them That Numbers Are A Part Of Everything We Do

Getting parents engaged in children’s education is recognised as critical to success, but it can feel like a challenge, especially when the subject is one that makes them anxious

- by Wendy Jones

Put yourself in the shoes of a parent. Your child has brought home maths homework. You’ve always hated maths – it just isn’t your thing. You don’t understand the methods they use nowadays, and it’s going to get worse as your child gets older and the maths gets harder.

That, sadly, is the reality for too many parents – and something that some schools are now addressing. Engaging parents in children’s education is recognised as critical to success, but it can feel like an intractable challenge for schools. And for maths education, there are extra hurdles. Besides the general reluctance that some parents feel about talking to teachers, there is the added problem of their own maths anxiety.

Abi Walton, deputy head at Laurel Lane Primary School in west London, says that parental attitudes to maths are not an issue that comes up during teacher training. ‘You’re taught how to show children maths strategies but not how to deal with parents who learnt a completely different way when they were growing up.’

Laurel Lane has been tackling the challenge of getting parents actively involved in their children’s maths learning. It is one of 28 London primary schools that took part in a project throughout the 2015/16 school year to improve parental engagement in the subject. Run by the Mayor’s Fund for London as part of its Count on Us campaign and the charity National Numeracy, it involved working with 6,500 children (Y1-4) and 3,000 families in areas of relatively high deprivation.

For Abi, one of the underlying strategies was to reveal ‘the bigger picture’ to parents who didn’t see the point of maths. ‘It was about showing them that maths is not just about the one-hour lesson but goes across the entire curriculum and, more broadly, that maths is part of everything they do.’

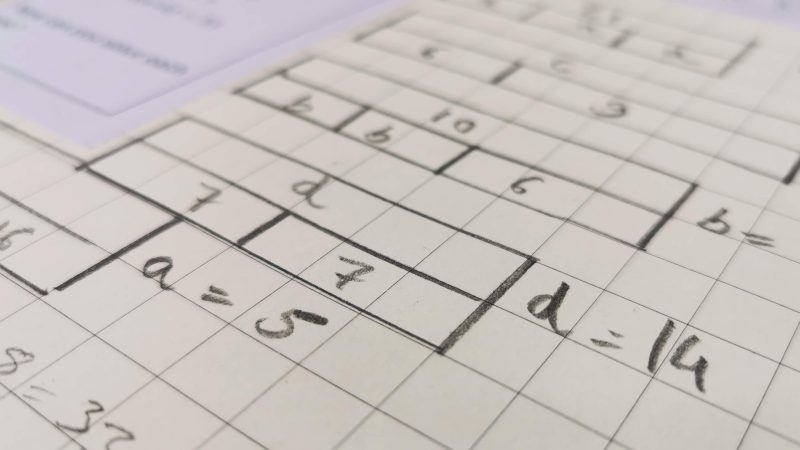

One of the first steps was to break down assumptions that maths homework is all about pages of sums. The introduction of National Numeracy’s family maths scrapbooks helped with that and involved presenting children and parents with problems that they could do together that were related to everyday life, but still linked to the national curriculum.

An initial letter went out to parents explaining the new approach and over the following months there were coffee mornings, evening events, regular sessions to share good ideas and adult numeracy workshops. There was also a maths challenge in the weekly newsletter, a dedicated area on the school website and a special number day where parents were invited into school. The aim of all this, says Abi, was ‘to get rid of the stigma attached to maths and make it more fun and interactive’.

At the outset, each school was helped to audit current activity and draw up its own action plan. This might include maths surgeries, quiz nights, and display noticeboards featuring photos of ‘maths in action’ at home. Successful activities often involved getting the children to explain the maths to their parents.

In many schools, parental engagement was low to start with – and not just in maths. The project director, Di Hatchett, a former primary head and director of the Every Child a Chance Trust, says the parents that schools really needed to reach were those who didn’t turn up for events. ‘Schools need to find ways round this. That might mean having a dedicated person to engage with parents at the school gate. It doesn’t have to be a teacher. TAs might feel more accessible for parents who are only ever called into school when something’s gone wrong.’ Downshall, a large primary in north-east London, had been told by Ofsted that it was not doing enough to engage parents, most of whom did not have English as their first language. So, as part of the maths project, it set up a Family Learning Club, getting parents to work with their children on, for example, money skills. And the parental engagement officer was in the playground at the start and end of the day to encourage the most reluctant to come along. Teachers, parents and children at the participating schools were asked to fill in online surveys at the beginning and end of the project. The vast majority of children and parents said the activities had made them more confident with maths. Teachers reported greater concentration and willingness to talk about maths among their pupils – and, perhaps most significantly, the proportion of pupils who did better than expected in teacher assessments went up from 24% to 45%.

Many of the schools are now continuing with the approach. The Mayor’s Fund offers a good practice guide to encourage schools to adopt their own parental engagement policies for maths, with an online training package due by the summer.

The project itself was not perfect. A few schools found the burden of reporting back too great and did not contribute to the final survey. Some felt the literacy levels of the scrapbooks were too high for some parents and that is being addressed. And although the proportion of parents who attended maths events rose to almost half, that still leaves a lot of parents out in the cold. There is a great deal more to do.

But it did show what is possible and many of the schools are enthusiastic about continuing with the approach. At Downshall, parental engagement is now built into all planning, so whenever any new activity is discussed, the key question is always, ‘How are parents involved in this?’

5 steps to engaging parents in maths

1. Make a plan Decide what currently works well and what doesn’t and what the barriers are; set a timescale and decide how you’ll measure the results. There’s further help from National Numeracy’s Family Maths Toolkit (familymathstoolkit.org.uk), with an ‘audit tool’ to get you going. Find the Mayor’s Fund for London good practice guide at mayorsfundforlondon.org.uk, with online CPD to follow.

2. Involve the whole school This starts with the senior leadership team but everyone – staff, governors, parents and children – needs to be on board and understand what it’s about.

3. Communicate Use all the methods you can think of – newsletters, texts, posters, letters from children, face-to-face reminders. One size doesn’t fit all, so you may need different approaches for different parents. Think about having a parental engagement officer or parents’ champion. This can be a teaching or non-teaching staff member, governor, community volunteer or parent.

4. Encourage parents (and – it should go without saying – teachers) to be positive about maths If they are negative, that’s the message children will pick up. Help parents to think about the maths of everyday life. Offer resources that children can take home to enjoy with their parents, eg puzzles rather than pages of sums.

5. Recognise that some parents need help with their own maths Consider how you can boost their confidence and improve their skills through activities at school. Tell them what is available in the community or get them to try the online National Numeracy Challenge.

Wendy Jones is a journalist, former BBC education correspondent and a founding trustee of the charity National Numeracy.